Portraits, frames and technology by Rebecca Milner

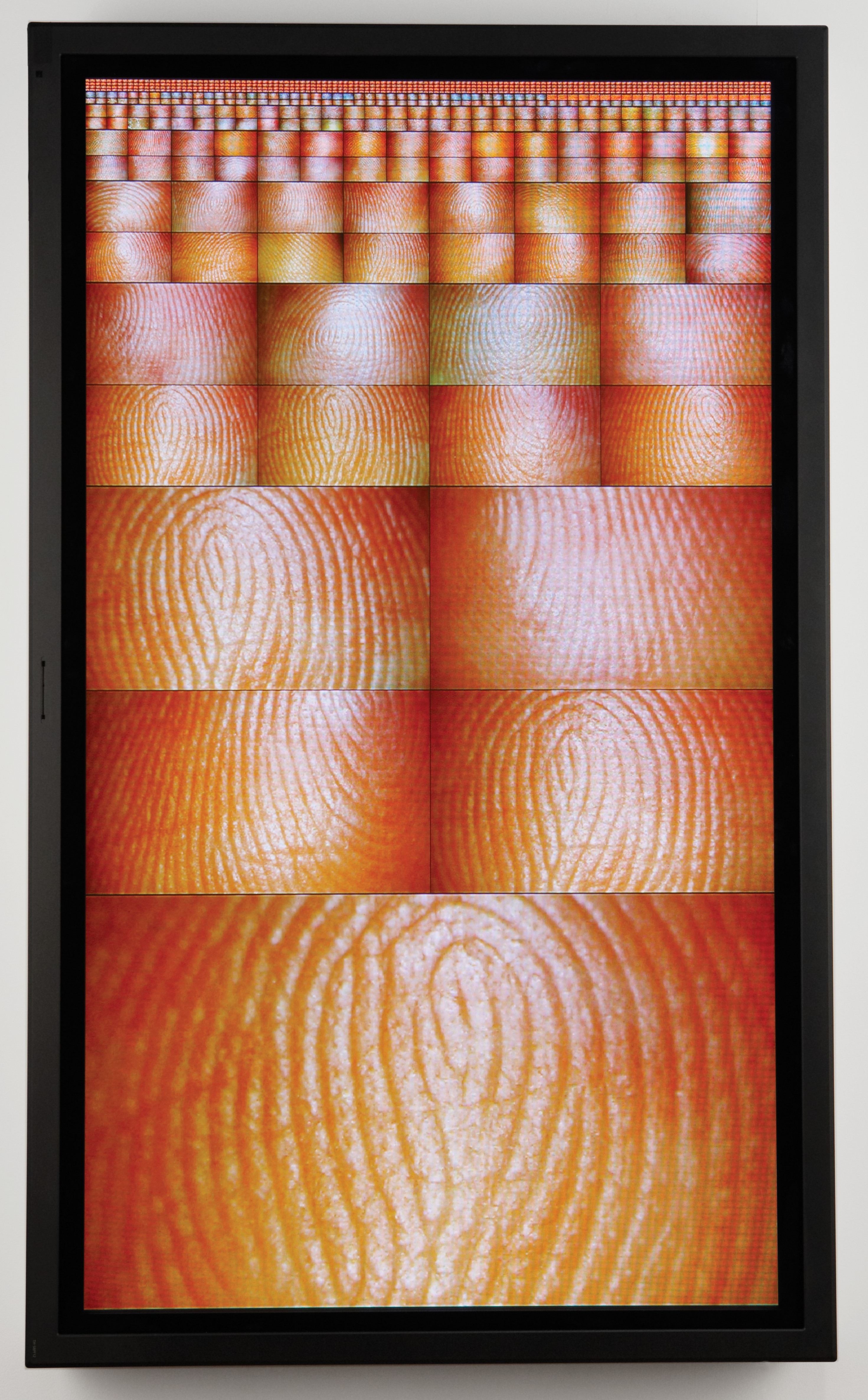

Pulse Index, 2010, Rafael Lozano Hemmer - AntiModular Research © Rafael Lozano Hemmer - AntiModular Research

Last month I attended the excellent Portrait Network seminar Copy, Version and Multiple: the replication and distribution of portrait imagery. I was particularly interested in the papers on Lely’s studio practice and Victorian carte-de-visite portrait photographs but the last talk of the day by video artist Marty St James resonated unexpectedly with another area of interest.

In September last year I gave a talk to a group of Manchester Art Gallery Friends about 19th century artist-designed frames. We have great examples in the collection by the Pre-Raphaelites and neo-classical artists such as Leighton and Alma Tadema. Frames are generally not interpreted in galleries and there have been few exhibitions on this subject – the NPG has been pioneering in this field staging The Art of the Picture Frame in 1996-7 and collating research online.

The Pre-Raphaelites started designing frames because they wanted more aesthetic control and to enhance the meaning and display of their work. Marty St James’ talk about his video portraits raised interesting questions about framing and artistic control in relation to technology and has inspired me to explore the idea of technology as frame further.

In the 1980s when St James started his video portrait work the hardware available to him to display it on were heavy black box TVs. A good example of this is his 1990 portrait commission for the NPG of the swimmer Duncan Goodhew, made with artist Anne Wilson (right).

Original installation view of the portrait of Duncan Goodhew (1957-), swimmer, by Marty St James and Anne Wilson, multi-monitor video portrait, 1990 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Because of the size of the monitors this portrait has a physicality which gives additional presence and power to the multiple images making up the work. As technology has developed and screens have become lighter, flatter, clearer and almost any size possible, St James is no longer so constrained by the size and look of the hardware. Some of his more recent digital video portraits have been framed with more traditional picture frames, for example, the miniature objects video portraits. As some of these works were commissioned as interventions into historical displays, that it is now much easier to hide technological hardware probably helped the video portraits ‘fit in’ to the aesthetics of an existing display. The invisibility of the hardware also means that the impact of the work centres on the tension between modern moving image and static ‘historic’ frame without the distraction of visible screens, wires etc. This tension is playful and arresting, drawing the viewer to watch the portrait within.

Pulse Index, 2010, Rafael Lozano Hemmer – AntiModular Research

© Rafael Lozano Hemmer – AntiModular Research

Reflecting on St James’ work reminded me of a digital artwork by Rafael Lozano Hemmer called Pulse Index which Manchester Art Gallery acquired in 2011 (left, and top left).

This interactive work records participants’ fingerprints at the same time as it detects their heart rates. It consists of a 50″ plasma screen, a digital microscope and pulsimeter contained within an aluminum wall mounted casing and a mini-mac (to run custom-made software). To participate, people introduce their finger into a sensor equipped with a digital microscope and a heart rate sensor; their fingerprint immediately appears as a fleshy-coloured abstract image on the largest cell of the display, pulsating to their heart beat and for a brief moment their image and information dominates the screen. At any one time, data for the last 509 participants is on display in a stepped grid of glowing skin. As more people try the piece and leave a trace of themselves in the artwork’s memory one’s own recording joins a community of previous participants and travels upwards until it disappears altogether — the artist describes it as ‘a kind of memento mori using fingerprints, the most commonly used biometric image for identification’.

Hemmer’s work is sinister and unsettling as well as intriguing and playful as you figure out how it works. It reflects how imagery and data is consumed through the ‘frame’ of technological devices as well as reminding us that we are not completely in control of all aspects of our identity as information is copied, multiplied and disseminated in increasingly complex ways.