Understanding British Portraits Annual Seminar, 29 November 2017 by Dr Kate Bethune

Queen Elizabeth I attributed to Nicholas Hilliard,16th Century. Waddesdon (Rothschild Family) © Hamilton Kerr Institute

The UBP Annual Seminar, held at the National Portrait Gallery in November, was my first encounter with the network. They say first impressions count the most, and I certainly wasn’t disappointed.

Having recently joined the National Trust as a Regional Curator with responsibility for all properties in Dorset, I am making it my priority to tap into as many specialist networks as possible in order to meet colleagues from a range of organisations and, in the case of portraiture, to grow my knowledge of a subject area and medium in which I don’t have much prior experience. (Previously I worked in the Furniture, Textiles and Fashion department at the V&A, before working as the Director’s Researcher for two years – so I’ve had something of a leave of absence from collections and curatorial work and now find myself in an extremely broad role which spans many periods, disciplines and media).

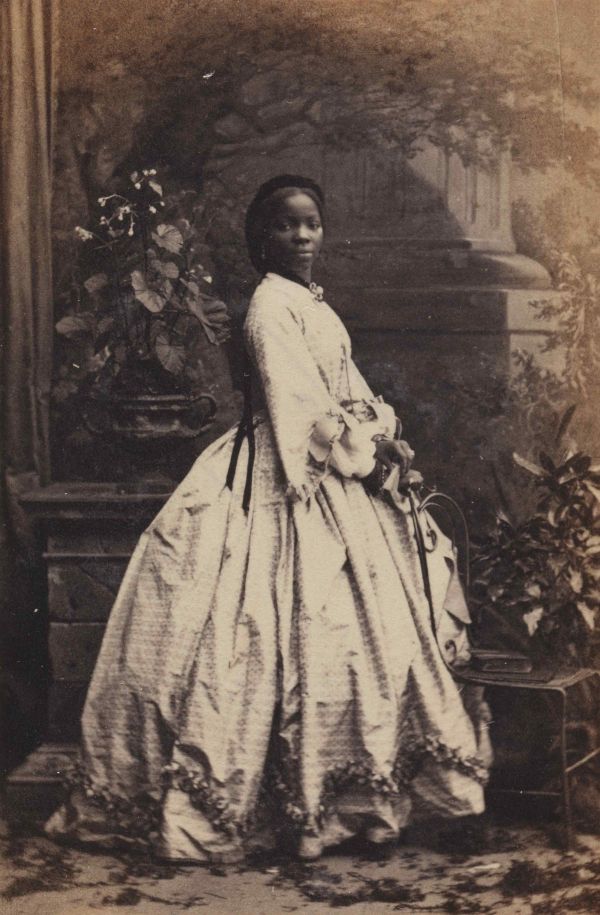

The UBP annual seminar was enormously useful to me in this regard. While the wide range of papers piqued my curiosity to learn more about subjects as diverse as the underrepresentation of black people in visual culture to the significance of pets in Victorian family photo albums, I also benefitted greatly from hearing people speak in their many different capacities as curators and collections managers, researchers and writers, and learning and interpretation specialists. The specific insights and perspectives each speaker brought to their approach to reading, interpreting and presenting portraits gave me much to consider as I take my own work forward with the National Trust and think about the multiple audiences the organisation is trying to engage through displays that move, teach and inspire.

I really enjoyed the balance between fine art and photography that ran through the panels, and I took something away from every paper. Three, however, resonated particularly strongly with me: Dr Juliet Carey’s opening paper on curating a display of Elizabethan portraits at Waddesdon Manor, Renée Massai and Helen Whiteoak’s paper on Black Chronicles, part of which major programme was a partnership between Autograph ABP in Shoreditch and the National Portrait Gallery, and Alice Cox’s insights into co-curating Refracted with volunteers at the Russell-Cotes in Bournemouth (my new local museum).

Being relatively new to the National Trust, it was really useful to hear about the experience of curators working in other regions. I really appreciated Dr Carey’s honesty regarding the diplomacy and level of compromise required of her in working in an historic house where the family are still actively engaged in its presentation. Accommodating Lord Rothschild’s request to include Lucien Freud’s portrait of Elizabeth II in a display whose focus lay more than 400 years earlier in the court of Elizabeth I at first seemed questionable. Had the display’s integrity been compromised? Or was her acquiescence inspired? I found in favour of the latter, for direct relevance aside, the Freud gave visitors a contemporary point of reference which prompted consideration of the role portraits still play in supporting public images of royals. And it demonstrated the importance of finding contemporary currency with the work that we do if we are to successfully engage broad audiences.

From Renée Massai, Helen Whiteoak and Alice Cox, I was reminded of the power and impact of collaboration. Whereas the partnership between Autograph ABP and the NPG resulted in a ground-breaking display on a new subject, and which attracted a new and more diverse audience to the NPG, at the Russell-Cotes staff and volunteers worked closely together to jointly navigate the exhibition-making process. I was deeply inspired by this model of working with volunteers. It felt bold to allow them so much agency and influence in shaping the exhibition’s concept, narrative and content. Yet this approach is precisely what made the exhibition so successful, and even possible, given the tight timeframe and limited staff resource available. Hearing from Alice has made me open to trialing new ways of working with volunteers – who also are vital to the work of National Trust and number more than 60,000 – and showed me what can be achieved when curators are willing to relinquish control.

Both papers also gave me much to think about in terms of the type of displays that curators should be aspiring to curate. Black Chronicles and Refracted both put communities who still remain largely underrepresented in our visual cultural history centre stage. And both papers were testament to the significant contributions that even relatively modest displays can make in redressing the imbalances that persist. As Renée reminded us, sometimes the imbalances are just as much a product of prior curatorial agendas as they are a consequence of entrenched historical narratives.

Although these three papers resonated most strongly with me, I gained something from every single one. And I absorbed a lot of technical information too. From Jim Cheshire’s paper on ‘Tennyson, Photography and Portraiture’, I learnt that an engraving of a sculpture won’t have pupils because sculpture is idealised – something which I am sure is obvious to many, but is not something I had stopped to think about before. And I started my long journey of learning about technique with Louise Cooling’s insightful assessment of the Edwardian miniaturist Louise (Louie) Burrell, as she explained the evolution of Burrell’s art from a stippling technique to a more linear style exemplified by hatching and with the use of a pin to achieve texture for features such as the hair.

In other papers I found yet more connections with my work at the National Trust. While Paul Holden gave fascinating insights in the painstaking work that has been undertaken at Lanhydrock to digitise the 7,000-strong collection of family photographs, Jane Hamlett’s paper, ‘Pets in Victorian Family Photograph Albums’, made me think about Max Gate, Thomas Hardy’s home in Dorset (for which I am Curator), and the importance of animals to the author and his first wife Emma. It’s an area I am certainly keen to pursue as I give more thought to evoking the Hardys in a house that lacks an indigenous collection of material artefacts.

And finally, Lucasta Miller’s paper on the ‘female Byron’, Letitia Landon, reminded me of the many codes that are embedded in portraits as well as their agency in ‘posturing’ on the public stage. I will take this with me as I start to consider how one of my properties, Kingston Lacy, will mark the 400th anniversary of the birth of Sir Peter Lely, by celebrating our important collection of Lely’s portraits of female sitters.

I gained so much from the UBP Annual Seminar: technical knowledge, insight into curatorial best practice, having my interest in portraiture piqued by inspiring speakers who engaged with diverse and fascinating topics, and the opportunity to network with a great range of delegates. It was a truly enriching day and I look forward to future events.