A newly-discovered portrait of Joseph Leftwich by ‘Whitechapel Girl’ Clare Winsten, c.1919, by Sarah MacDougall, Ben Uri Gallery & Museum

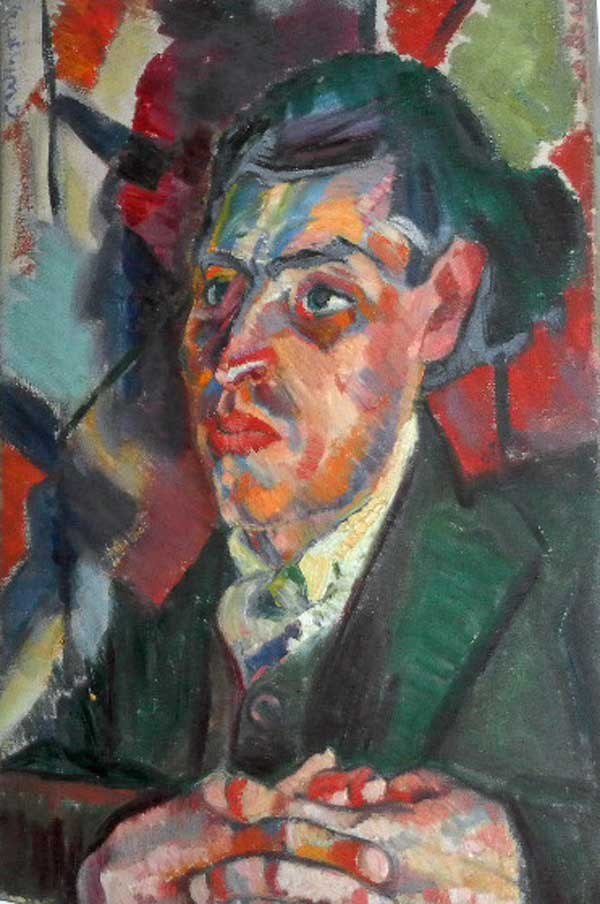

Portrait of Joseph Leftwich by Clare Winsten, c.1919, Ben Uri Gallery & Museum

My co-curator, Rachel Dickson, and I were delighted when, in the summer of 2015, just as we were preparing to celebrate Ben Uri’s centenary with a major collection exhibition, Out of Chaos, at Somerset House, this early oil by Clare Winsten (1892–1984) came to light. A portrait of one European Jewish émigré to London by another, it depicts the Yiddish writer, critic and translator, Joseph Leftwich (1892–1983), the key chronicler of the so-called ‘Whitechapel Boys’, fittingly executed by the only ‘Whitechapel Girl’.

Born in Zutphen, Holland of Polish-Jewish parents, Joseph Lefkowitz moved with his family to England from Cologne when he was nearly seven, following the tragic death of a younger sibling. As an ‘English school boy, in a Whitechapel board school’, he witnessed both Queen Victoria’s funeral and King Edward VII’s coronation, but living at the heart of London’s Jewish quarter, he immersed himself in its vibrant Yiddish culture. Initially, he worked as a furrier, afterwards writing for the Yiddish daily, Di Tsayt, and together with John Rodker and Clare Winsten’s future husband, Simy Weinstein, co-founded the Whitechapel group of aspiring poets. From 1911, as Leftwich’s diary documents, they were joined by the diffident poet-painter, Isaac Rosenberg, then studying at the Slade School of Art, who soon introduced his fellow students: East Enders Mark Gertler and David Bomberg, as well as two scholarship boys from the North of England, Jacob Kramer and Bernard Meninsky, all recipients of grants from the Jewish Education Aid Society. Today, it is primarily these artists, who both individually and collectively made a distinct contribution to British modernism in the years leading up to the First World War, to whom this group name is more commonly applied. Yet they came together only once in May 1914 in the much-analysed ‘Jewish Section’ co-curated by Bomberg and the sculptor Jacob Epstein within the Whitechapel Art Gallery’s exhibition Twentieth Century Art: A Review of Modern Movements, which brought together this locally nurtured talent with a smattering of ‘foreign’ Jewish artists: Modigliani, Pascin, Nadelman and Kisling, many of whom they had met in Paris. Clare Winsten (then Clara Birnberg), who had transferred to the Slade on a scholarship from the Royal Female School of Art (later the Central School), was the lone woman among the 14 artists represented.

Winsten settled in London’s East End with her family c. 1902, after travelling via Germany, having been born a decade earlier in Romania, where her parents had fled from the pogroms, abandoning a comfortable, middle-class lifestyle in their native Tarnopil, Galicia (now Western Ukraine). Sensitive to her origins, she referred to herself – with a nod to her future neighbour George Bernard Shaw – as a ‘downstart’. Very much the ‘new woman’, she cropped her hair, was a vegetarian and a member of the Women’s Freedom League suffragette movement, retaining a lifelong commitment to humanitarian causes. Her years at the Slade (1910–12) coincided with Roger Fry’s two seminal Post-impressionist exhibitions and their explosive impact on British modernism did not leave her own work untouched. She overlapped with Gertler, Bomberg and Rosenberg, sitting for both the latter (Rosenberg’s portrait of her is the Slade Collection, UCL), sketching a series of reciprocal portraits of Rosenberg and working for a time along similar lines to Bomberg, although they later fell out irrevocably and she recalled him in her (unpublished) autobiography with much bitterness. A certain restlessness and dynamism in her work of this period suggests a kinship with the nascent Vorticists. During the First World War, she married Weinstein, a fellow Pacifist, afterwards imprisoned (along with Rodker) as a conscientious objector for three years; postwar they anglicized their names to Stephen and Clare Winsten, later embracing Quaker humanism.

Winsten’s portrait of Leftwich with its bold palette and fractured background, probably painted just after the war, shows her continuing engagement with modernism. Portrayed without his ubiquitous round-rimmed spectacles, Leftwich somewhat resembles his friend Rosenberg, killed in 1918 in the trenches in France. The remaining ‘Whitechapel Boys’ were scattered by the war. Acquired at the eleventh hour, with support from the ACE / V&A Purchase Grant Fund, the Art Fund and private donors, this portrait was aptly exhibited within the ‘Conflict and Modernism’ room at Somerset House as part of our centenary exhibition (reprised and extended as 100 for 100: Ben Uri – Past, Present, Future, Christie’s South Kensington, 2016), and now touring to the Laing Gallery, Newcastle (until 26 February 2017), restoring Winsten’s rightful place among her Whitechapel peers. A significant addition to Ben Uri’s rich Whitechapel group holdings, the portrait is also contemporaneous with Ben Uri’s own Whitechapel birth.

Today the Ben Uri collection comprises over 1300 works across 30 different mediums by more than 400 artists from 35 countries. This is our third likeness of Leftwich, but the first by a Whitechapel cohort, and joins four further Winstens in the collection including an early competition piece, Attack (c. 1910), executed at the Slade. We are particularly proud of the number of female artists in our collection (27% in contrast to the national average of 4%) and this acquisition cements links between other women collection artists: Winsten also studied lithography at the Central School, where her autobiography records her gratitude for the friendship of another older female student, Amy Drucker (1873–1951) and Winsten’s sketches also include one of the young artist Clara Klinghoffer (1900–1970) – a ‘Whitechapel Girl’ of the next generation.

Comments

This is a fantastic painting. I knew Joseph Leftwich as a child growing up in London, where he and his wife, Sala, were friends of my parents, probably a legacy from my father’s parents who were

Polish refugees from Vienna, my father arriving in the UK with his mother in 1938 as a 13 yr old. I have learned, since becoming an adult, what a huge and interesting part he played in the art and politics of the early 20th century.

It is remarkable that as a poet myself I took the same solitary walk though as Leftwich except to go to Liverpool st station where I obtained solace and write my poetry.