‘A pleasing black silk string’: looking at portraits in the Fanshawe collection at Valence House by Rachel Church

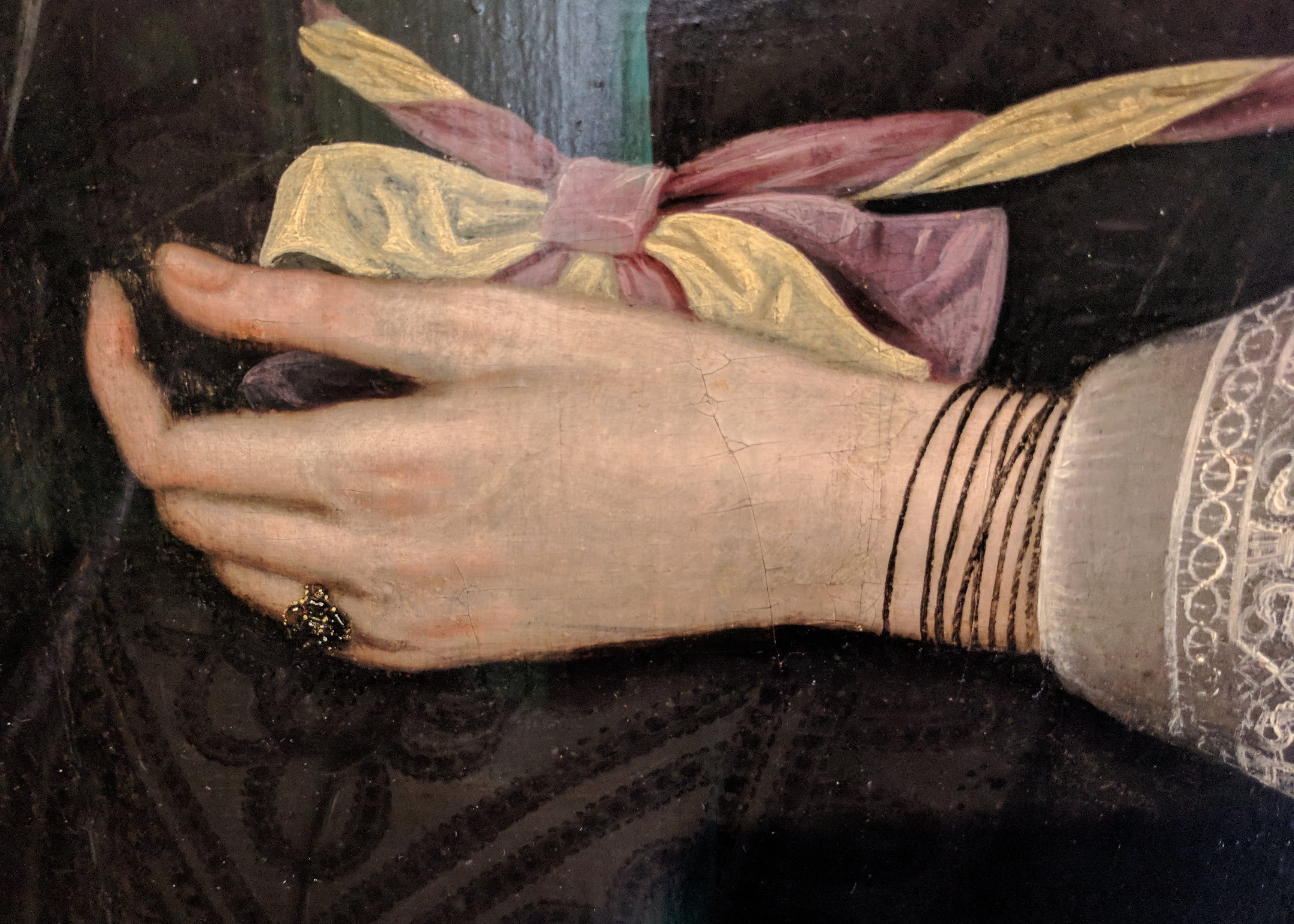

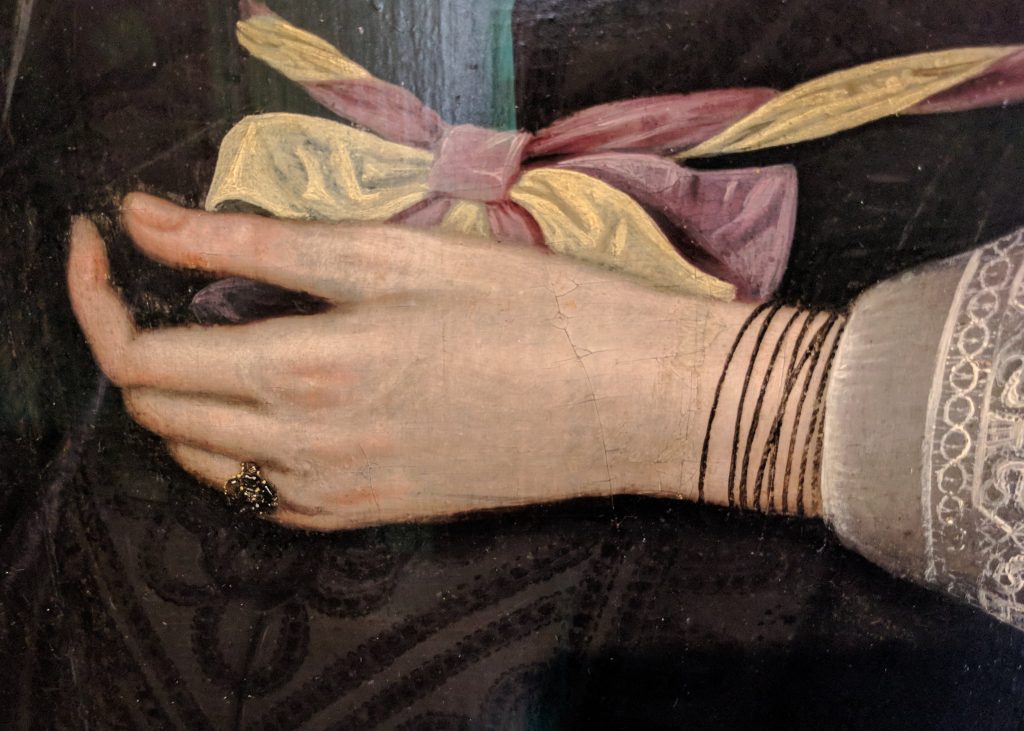

Portrait of Anne Fanshawe (1607-28), 1st wife of Thomas 1st Viscount Fanshawe by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, c. 1628 (detail), Valence House Museum, LDVAL 11

A thin, black thread wound around the wrist of Anne Fanshawe in her 1628 portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger drew me to the study day at Valence House Museum, Dagenham, organised by the Understanding British Portraits network- but more of that later. As a curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum, I have researched the rings collection over a number of years and am always interested to find new sources of information.

The intrinsic value of jewellery, historically made of precious metals and gemstones, made it very vulnerable to being lost, stolen, altered or melted down to be remade in the latest fashion. Portraits can therefore offer clues showing what jewellery was worn, how it fitted with dress fashions and how this intersects with social class. The collection of Valence House includes a large, historic collection of portraits from the Fanshawe family along with the associated paper archive. The earliest Fanshawe portrait may be that of Henry (1506-68) and the latest include Captain Aubrey Fanshawe (1893-1973) who donated the collection to the Borough of Dagenham in 1963. I was attracted by the opportunity to see this group of portraits and to see whether the portraits would shed any light on the jewellery chosen by the Fanshawes and the way in which they chose to have themselves represented.

Portrait of Anne Fanshawe (1607-28), 1st wife of Thomas 1st Viscount Fanshawe by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, c. 1628, Valence House Museum, LDVAL 11

Enamelled gold ring , set with rock crystal, similar to that worn by Anne Fanshawe V&A M.20-1929 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The Fanshawe family were a prominent part of Barking and Dagenham society, owning the manors of Jenkins and Parsloes as well as Valence House itself. They were a middle class family who had seen a rapid rise, notably Henry Fanshawe’s appointment as Remembrancer (or tax collector) to Elizabeth I, a position with obvious possibilities and which was subsequently made hereditary. The Fanshawes were therefore a family of some note with court connections, and the opportunity to view a family through generations of portraits was not to be missed.

The day began with a presentation by Leeanne Westwood, the curator at Valence House and Understanding British Portraits Research Fellow. The collection includes paintings by Peter Lely, Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger and Mary Beale which Leeanne has been researching during her Fellowship. Leeanne explained what the collection included and how the paintings had come to Valence House. A general discussion followed on the Fanshawe custom of having paintings copied and other participants offered thoughts on how typical this was and suggested other family portrait groups which might be comparable.

The group was then taken around the museum for a personal introduction to the Fanshawe portraits on display by the extremely knowledgeable museum guide Deirdre Marculescu (known in the museum as Lady Fanshawe) and then, the favourite moment for any museum curator – a visit to the stores. This was an opportunity to look closely at the paintings and for me to scrutinise details of the dress and jewellery. The explosion in online cataloguing, photography and digitisation has been a wonderful resource for researchers, making information more freely accessible than ever before but nothing quite replaces first hand observation, especially for details which are frustratingly hard to see on a photograph.

Portrait of Anne Fanshawe (1607-28), 1st wife of Thomas 1st Viscount Fanshawe by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, c. 1628, Valence House Museum, LDVAL 11

One of the details I had been keen to examine was the thread wound around the wrist of Anne Fanshawe in her portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts (c. 1628). This seemed to form part of a short lived fad for wearing jewellery on black strings – sometimes rings hung from a cord around the neck, more rarely a cord wound around the wrist and looped through a finger ring. Sometimes, as in Anne Fanshawe’s portrait, the thread is wound around the wrist alone, occasionally with added decorative loops. This fashion can be seen most frequently in paintings by William Larkin, Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder and Younger, Robert Peake but also Paul van Somer, Johannes Priwitzer and Peter Paul Rubens. The fashion had a short vogue from around 1610 to the 1630s and the reasons behind it are still unclear. One suggestion was that the cord helped a loose fitting ring to stay upon the finger, but the prevalence of portraits showing a black thread alone makes this unlikely. More probable is the idea that the thread served to set off the fashionable whiteness of the skin. In 1637, the Dutch writer Johannes van Heemsberck described a woman dressed up as a stylish ‘shepherdess’- around ‘the neck …(doubtless to set off the white) she had a pleasing black silk string, on which was dangling a small golden ring with little diamonds.’

When using portraits to shine a light upon jewellery, key questions include not only how closely the painting mirrored existing objects and how they were worn but also whether the painting itself has been altered from its original state. This problem was addressed by the talk given by two current Courtauld Institute of Art students, Olivia Stoddart and Saskia Rubin, part of an imaginative project pairing art historians with conservators. It would be interesting to know whether the black cord around Anne Fanshawe’s wrist, for instance, ever extended to her diamond ring?

Karen Hearn’s fascinating talk on pregnancy portraits, Gerry Abalone’s discussion of auricular frames and Karen Rushton’s talk on the Fanshawe family archives also prompted the discussions and exchanges of information between the participants that make these events so valuable. I am most grateful to the ‘Understanding British Portraits’ network for supporting this event and to Leeanne Westwood and the staff of Valence House Museum for organising and hosting it.

Comments

I would like to speculate that the black thread wound around the wrists and/or fingers of women or girls in various portraits is in some way connected to a mourning custom. The women in the portraits are dressed in black which usually signifies mourning. In the portrait “ Three Young Girls “ from The Berger Collection in the Denver Museum of Art, it is believed that the mother has died. With regard to the black strings around necks with a ring attached, perhaps the ring is a memento of the deceased person.

I have been very curious about the black strings and offer this explanation.