A Portrait of Coronavirus by Anna Linch and Dr Mark Linch

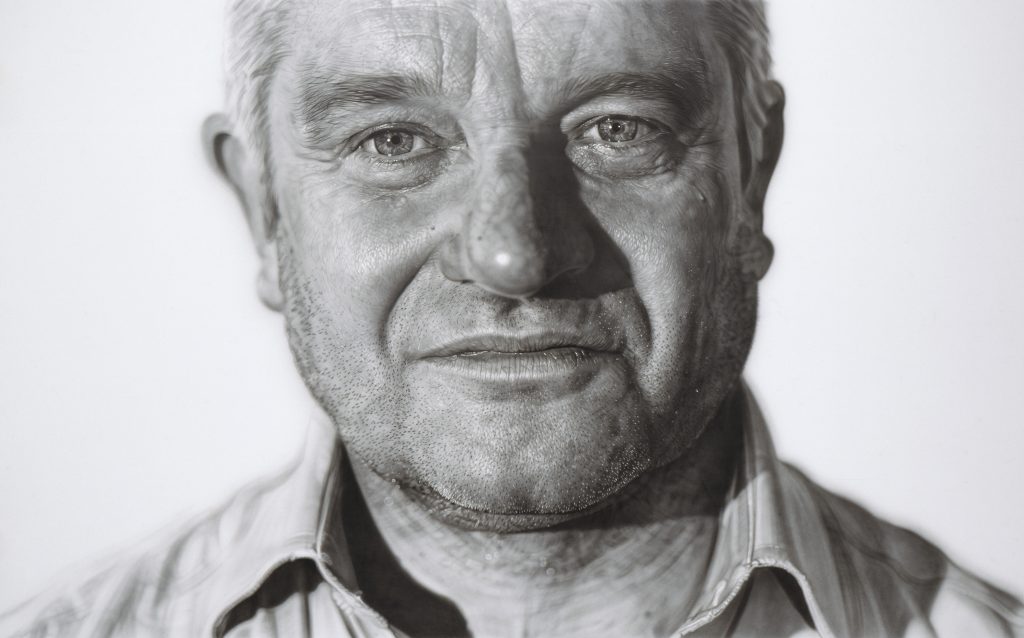

This is What Broken Looks Like, by Ceri Hayles, 2020, from the National Portrait Gallery’s Hold Still exhibition © National Portrait Gallery

Coronavirus: a noun familiar to everyone today, but perhaps lesser known before the pandemic, unless you work in the field of science or medicine. COVID-19, or its longer name of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has dramatically changed society and will undoubtedly be taught in history lessons in the future. As we look to the scientists, doctors and policy makers to get us out of this pandemic here we present, through the lens of the National Portrait Gallery collection, historical pioneers and contemporary history-makers in the battle against COVID-19.

Human coronavirus was first described by virologist David Tyrrell in 1965 at the Common Cold Unit in Wiltshire, England. The virus was then imaged by June Almeida using an electron microscope, revealing a circular structure with distinctive spikes with rounded tips that reminded the scientists of the appearance of the sun’s atmosphere, known as its corona. This is the image that we are now all too familiar with due to its frequent appearance on news briefings. The virus had typically caused cold symptoms such as a sore throat, cough or stuffy nose, but its mild-mannered reputation changed in 2002 with the outbreak of SARS-CoV-1 in Southern China, which was far deadlier. In 2012 an even more virulent form of coronavirus, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV), was detected but fortunately had less than 2,500 cases. COVID-19 was first identified in Wuhan, China in December 2019. To date it has infected more than 93 million people worldwide with a death toll that has surpassed two million.

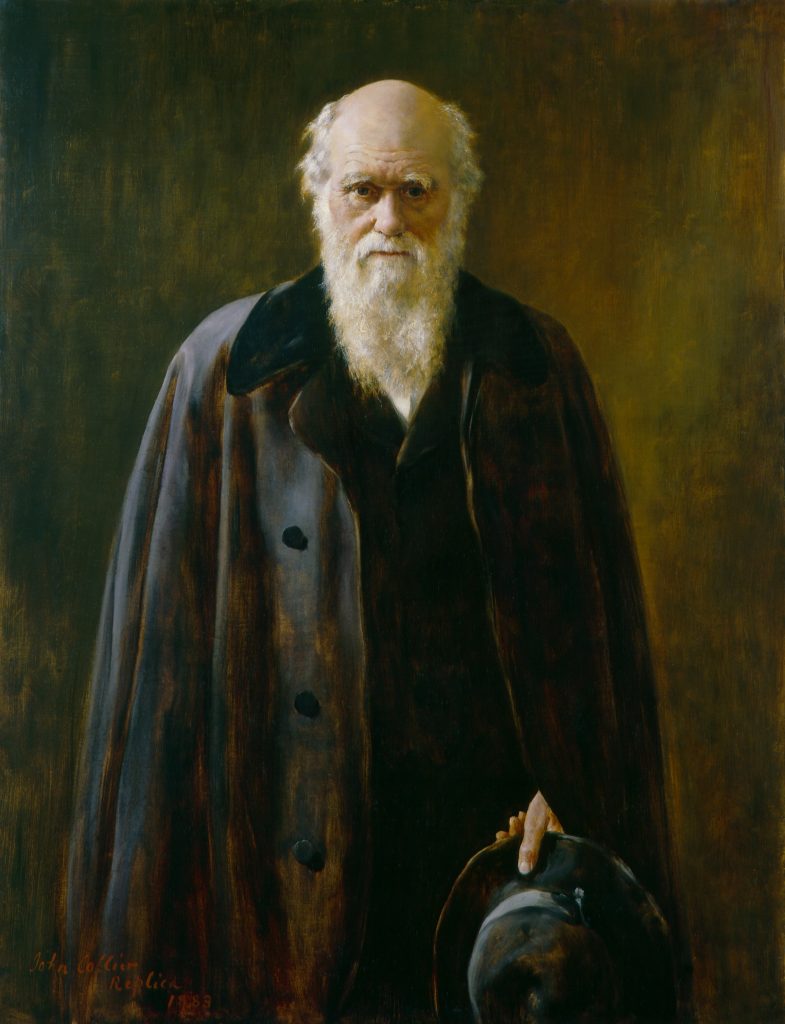

In humans, the virus continues to mutate leading to small changes, for example to the shape of the surface molecules. If these changes are beneficial to the survival of the virus, by making it more infective for example, then these new variants are likely to persist. There are currently several new variants that have evolved impacting the UK. It was Charles Darwin who first described the concept of these evolutionary changes in his book On the Origin of Species (1859). The rather mournful, imposing figure of Darwin has hung in the Gallery since it was given by the sitter’s son William Erasmus Darwin in 1896, as a constant reminder of the power of knowledge and understanding of our planet and its organisms. Using the principles laid down by Darwin, scientists will be able to study the evolution of COVID-19 to learn more about how the genes of the virus function, to track how the disease is spreading around the world and to work out what the most effective treatments will be.

- Charles Darwin copy by John Collier, oil on canvas, 1883, based on a work of 1881. NPG 1024 © National Portrait Gallery, London

- Florence Nightingale receiving the Wounded at Scutari by Jerry Barrett, oil on canvas, 1856. NPG 4305 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Ways of decreasing transmission of the virus are being uncovered. ‘Hands, face, space’ is a motto endlessly repeated at present and for good reason. Physical distancing and hand washing seem to be the most effective. Both are strategies that Florence Nightingale championed to decrease mortality rates following her experience of treating injured soldiers in the Crimean War. Barrett’s 1857 painting Florence Nightingale Receiving the Wounded at Scutari springs to mind with footage of crowded wards and exhausted hospital staff on the news. In this vast painting, Nightingale stands in the centre of an influx of wounded soldiers and staff awaiting treatment and direction accordingly. 2020 marked the 200th anniversary of Nightingale’s birth, so it was fitting to name the vast new treatment centres, such as the Excel Centre London, after her legacy.

Another great nurse and healer from the NPG collection, whose acts of kindness made a great impact on the soldiers in the Crimea, is Mary Seacole. In May 2020, a new rehabilitation centre for COVID-19 patients was opened in her honour. The NHS Seacole Centre at Headley Court, Surrey, has been providing specialist care for patients who are recovering from the disease in the Surrey region.

- Mary Seacole by Albert Charles Challen, oil on panel, 1869. NPG 6856 © National Portrait Gallery, London

- This is What Broken Looks Like, by Ceri Hayles, 2020, from the National Portrait Gallery’s Hold Still exhibition © National Portrait Gallery

The National Portrait Gallery’s community project Hold Still, spearheaded by its patron the Duchess of Cambridge, has paid tribute to the everyday population and unsung heroes of the pandemic. The gritty portraits of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) staff coming off a twelve-hour shift in full Personal Protective Equipment will be forever engrained in our memories. Often we have heard the analogy of a country at war. As Boris Johnson stands at the lectern in Downing Street flanked by scientific advisors during press briefings, we are reminded of the famous speeches of Churchill during World War II. This time our weapons are not the armed forces and ammunition, but scientists, healthcare staff, Track and Trace, treatments and vaccinations.

- Winston Churchill, by Cecil Beaton, 1940. IMW MH 26392 © IWM. Collection National Portrait Gallery, London

- Paul Nurse by Jason Brooks, acrylic on linen, 2008. NPG 6837 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Rapid testing is key to keeping the NHS workforce protected and active. Sir Paul Nurse, Director and Chief Executive of The Francis Crick Institute recognised this and mobilised the facilities of the Crick, the largest biomedical research institute in Europe, to provide rapid, accurate testing locally. This effort has supported ten London hospitals and 150 care homes in helping to keep thousands of staff and patients safe.

The UK has been at the forefront of clinical research to identify potential treatments for patients who are severely ill in hospital with COVID-19 pneumonia. The steroid dexamethasone and the arthritis medications Tocilizumab and Sarilumab all improve the odds of recovery for patients in ICU. However, the great hope to lead the world out of the pandemic crisis is through a global vaccination programme.

For the origins of vaccines we have to rewind to the Regency period and West Country surgeon, Edward Jenner who discovered the first vaccine. He had noticed that milkmaids who had had coxpox were unlikely to catch the much more deadly smallpox. He inoculated his gardener’s son with material from a patient’s cowpox sore and this prevented smallpox in the young boy despite multiple exposures. Northcote’s 1803 painting documents the role of Blossom the cow in Jenner’s pioneering work. Jenner sits in a contemplative pose beside a jar containing an injected calf’s hoof. Propped up beside him are a dismembered cow’s leg and his publication The Origin of Vaccine Inoculation. Although first published in 1798, it took ten years for the government to accept his discovery. Jenner campaigned vigorously for vaccination but never lived to see its widespread implementation. By 1853, vaccination was compulsory in Britain and Jenner was posthumously considered a national hero. He would be proud to know that a COVID-19 vaccine was developed at an institute in Oxford bearing his name.

There are now three different vaccines with regulatory approval. They work to mimic the spikes on the surface of coronavirus and prime the immune system for attack against COVID-19 if subsequently exposed to the actual virus. The global effort at containing the disease has now truly begun. This journey will continue; the virus will mutate, the human race will adapt, science will protect us and the National Portrait Gallery collection will grow. Who will be on the walls of the gallery to tell our current story to future generations? COVID-19 will leave a legacy and we must record it for future generations, not just through scientific journals, but through art as well. We are at a pivotal point of science and humanity coming together in a global effort to move forwards.

The National Portrait Gallery has an established Hospitals Programme promoting arts for health and wellbeing in five partner children’s hospitals in London: Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, Evelina London Children’s Hospital, Great Ormond Street Hospital, Newham University Hospital and Royal London Hospital. Thanks to support from property and real estate investment advisor Delancey and its platform businesses (Get Living, Here East and The Earls Court Development Company), the gallery is able to connect children and young people in hospitals with its collection and artist-led creative opportunities.

Comments

I didn’t think I could possible learn much more about Covid-19 – well I’ve been proved wrong. Thankyou.