A Welshman returns from Italy by Dr Paul Joyner

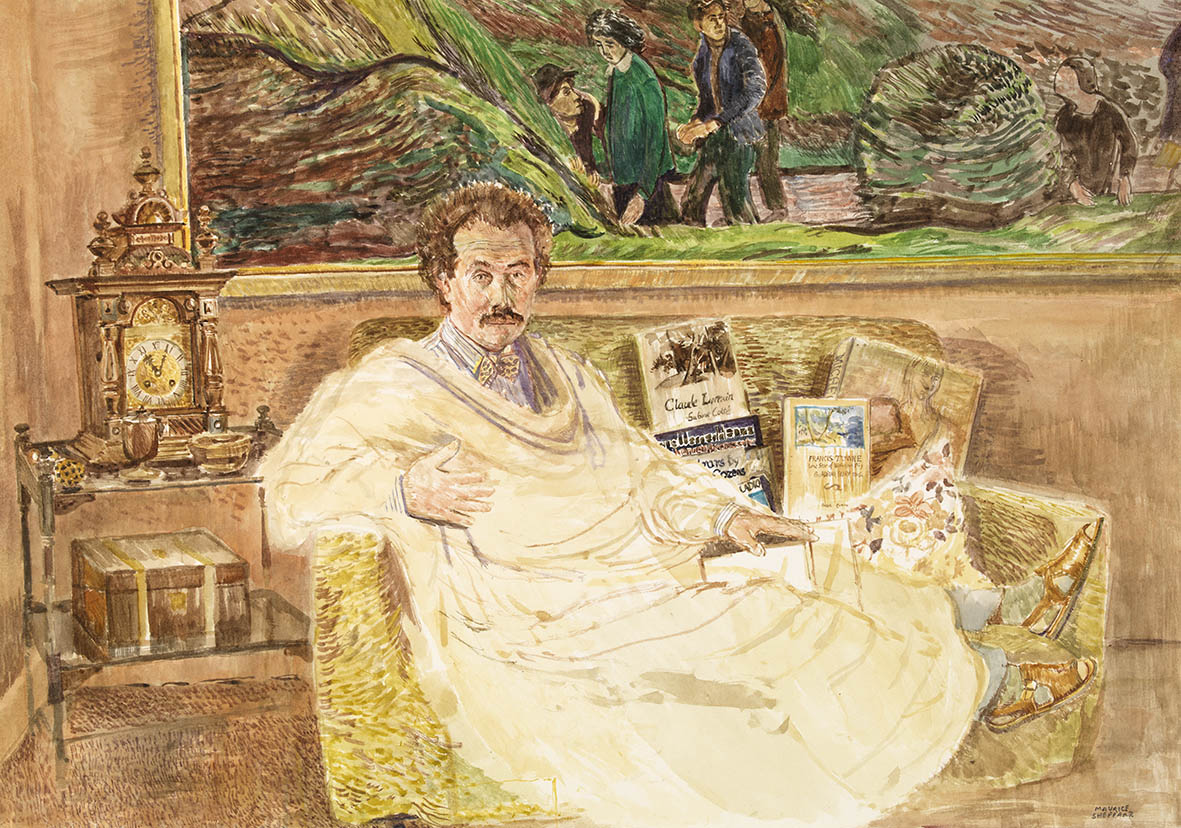

The Artist Returned from Italy by Maurice Sheppard, watercolour, 1985. National LIbrary of Wales © Maurice Sheppard PPRWS

This year we remember the Welsh artist Richard Wilson (1713/14-1782), who brought a good deal of the Italianate light a flavour to British art of a former age. He was not the only Welshman who found the Italian experience of great importance to his thinking and feeling for art.

Quite recently we were offered this watercolour by the Welsh artist Maurice Sheppard. It was donated to the Library via the Art Fund and represents the artist’s generosity and deep interest in artistic scholarship.

Maurice depicts himself in repose, feet up still sun-burnt from his trip. Behind he has placed some of the books which reflect his aspirations: Cozens, Towne, Michelangelo and of course Claude. At his head is a large canvas by his teacher and friend Professor Carel Weight which had been acquired by the artist many years before his visit and subsequent return.

Why does this portrait strike me as significant? Well firstly it shows the artist as observed observer. He is a reader of books, in fact, he needs to read several at the same time. I love the idea that here we have an artist who does more than paint, he thinks. I suppose it reminds me of the Poussin self-portrait of 1649 now at Berlin: in which Poussin stares at us with the same focus as Sheppard’s work. Both are determined to capture what or who is before them, as if that moment will be etched forever on some piece of paper or canvas.

But this is not just an artist looking, he is resting from his investigations in Italy and now spends time perfecting his vision, ready for another season of painting. Sheppard shows himself full with Italian ideas. I suspect that the cream blanket also echoes the togas he saw in various sculptures he saw on his travels – perhaps a resting philosopher in a Medici palace?

But from a curator’s perspective this self-portrait does more than record a home-coming. It reminds us that Maurice Sheppard is also an expert collector of paintings and drawings. Over the whole of his career he has made it a practice that he acquire works by artists he knows and many by artists of the past who he admires. The resultant collection is exquisite and enlightening. It displays all the usual techniques used by European artists over the last five hundred years; it also includes many experimental works which show the love of the material and the subject.

This collection was very generously donated to the National Library of Wales and forms an extensive research collection – very similar in intent to John Ruskin’s collection given to the Ashmolean. Sheppard’s collection is well over 500 individual pictures, mainly British and spanning the 1780s to 2000s – a rich source of delight for generations to come.

Self-portraits are one of my favourite sorts of portrait – because we see the artist as he wants us to see him. Many of our preconceptions concerning what the artist is intending are obsolete with the self-portrait – we are confronted with Sheppard’s vision of himself and the force of his intellect demands that we respond. Surely we need to ask the question why he is resting mid-morning? Could it be that the portrait is a statement of a new beginning, he has returned to new things.

Do we need this sort of serious approach to our collections and our art today – I believe we do – for all the instant messaging of electronic knowledge, careful contemplation brings fruit which stays fresh long after the Italian suntan has faded.

The Artist Returned from Italy by Maurice Sheppard, watercolour, 1985. National LIbrary of Wales © Maurice Sheppard PPRWS