Domestic interiors in the Archives: Mr & Mrs Robinson, Mrs Morice and Thomas Cromwell, by Sally Hoult

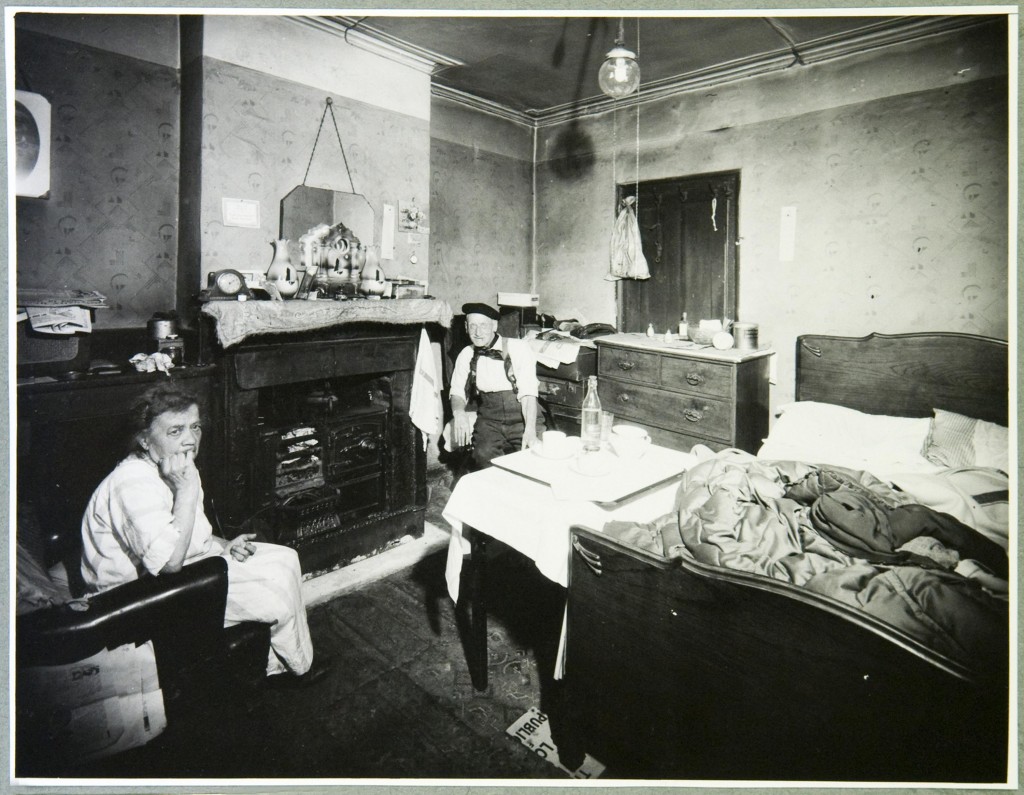

Detail from 'Mr and Mrs Robinson in their bed-sitting room' (National Archives, Kew, WORK25-200).

At the end of June, a colleague and I, attended the Understanding British Portraits seminar at the Geffrye Museum. We attended as part of a newly formed specialists’ records team here at The National Archives, looking specifically at our Design, Photographs and Art Collections.

As the archive of central government, the records we hold cover a span of around a thousand years. Within the context of our own images, I found the idea of the domestic interior in British portraits quite a challenging one. Nevertheless, we hold over a million photographs, covering the span of photography itself and thousands of pieces of artwork, plans and designs within our visual collections and also throughout our general collections, giving me ample food for thought.

I decided it would be interesting to show, three examples that we hold of domestic interiors in their very different guises and talk a little about the people and documents they relate to, whilst also giving some idea of the diversity of the documents we have within our collections and the time span they cover. I’m going back in time, starting with a photograph showing the interior of a bed-sit in 1950, followed by a watercolour of an interior of a dining room in the early 19th century, and lastly, and for me the most fascinating of all, an inventory of a private house in 1527.

Fig. 1. Mr and Mrs Robinson in their bed-sitting room (National Archives, Kew, WORK25-200). Click to enlarge.

This is a photograph of Mr & Mrs Robinson in their bed-sitting room at 33 Bygrove Street, Poplar, taken in June 1950. This photograph is rather sad by today’s standards, but it might not be sad to Mr & Mrs Robinson. We don’t know anything about them, except what we see. Their fortunes might have gone up with this their new bed-sitting room. Indeed, Mr Robinson looks quite happy. There is so much detail to be seen in this room I hardly know where to begin. I was immediately drawn to the painted floor, a much earlier detail. Under the bed and the table, the paint remains much brighter than the area which has been walked on. This floor painting would I think be more akin to the actual date of the room. The cornice looks Queen Anne or Georgian. The picture rail has been removed, but would have been at the height of the wallpaper, which has a distinctive 30’s feel; it is very grubby suggesting it has been there at least a couple of decades. I think this is a ground floor or semi basement room, judging by the cast iron range with its oven and hob, a kitchen or scullery originally. The bed with its wooden bed head and foot has simple brass embellishments, a much more modern piece of furniture. The single overhead light is brass and looks as if it has a pulley system to lower it to table height or a suitable height to light the gas mantel within the glass bowl. There are interesting objects on the mantelpiece. A mantle garniture of a china (or pottery) clock (the clock itself appears to be missing) with matching side vases; another clock and on the right some decorated tins. The mirror is hung from a chain and typical of the period. Old leather suitcases are stuck in the corner. I could go on endlessly. The most interesting thing I find about this room is the time span it covers through the things it contains, not necessarily belonging to but lived with by Mr & Mrs Robinson.

Fig. 2 ‘Mrs Morice’s Back Drawing Room’, 1830 (National Archives, Kew, PROB37-813). Click to enlarge.

Here we see a watercolour of a room which was commissioned by Wheeler & Batsford against Anderson; to be used as an exhibit in a dispute over the seventeen wills made by one ‘mad Mrs Morice’ in 1830. No one is in the room, but nevertheless we know it to be an interior of one of the rooms in her house. Mrs Morice calls it her ‘black diamond room’. It is in fact her Back Drawing Room, I think a dining room, as amongst other things there is a knife box, which would only be kept in a dining room and some tea caddies. Most importantly, in the centre of the room there is a very large mound of coal (black diamonds)! The lawyers won their case against her. They argued that if she kept coal on her sitting room floor, she could hardly have been of ‘sound and disposing mind’.

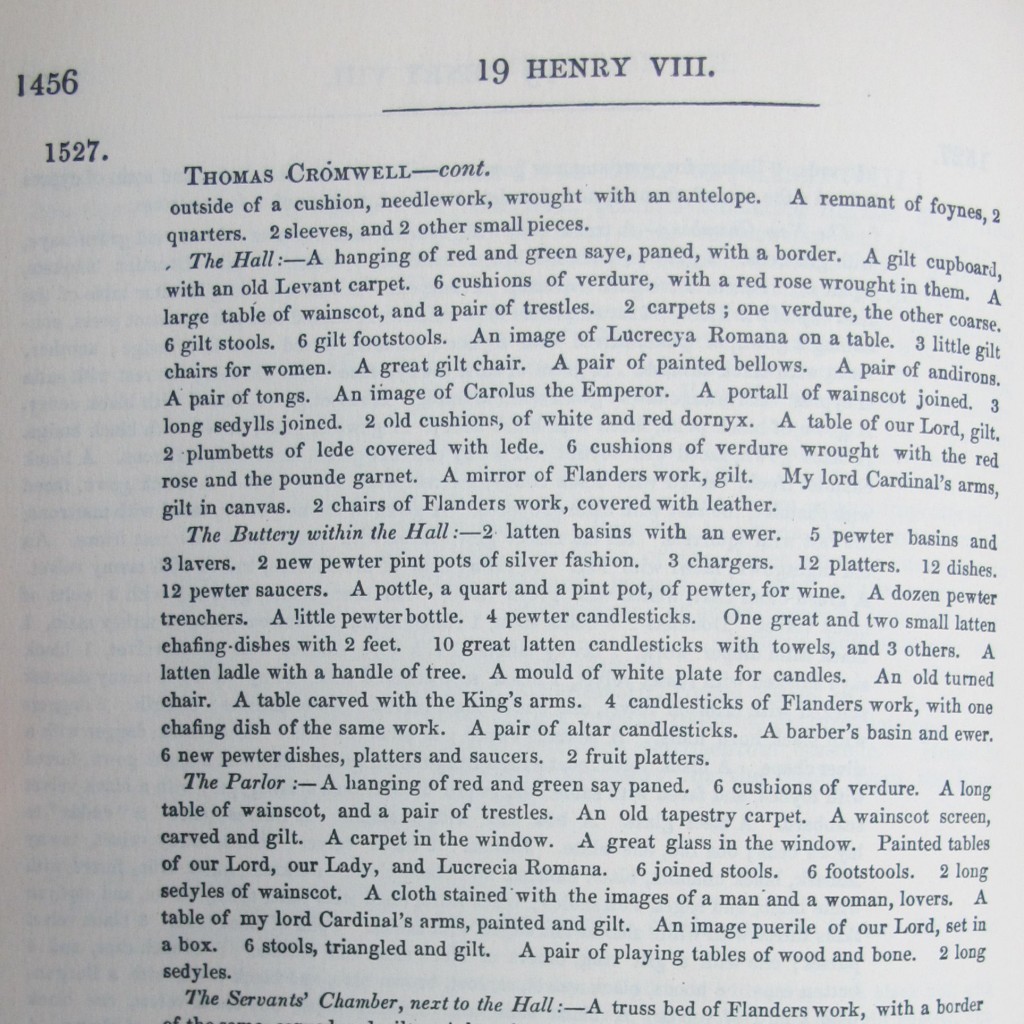

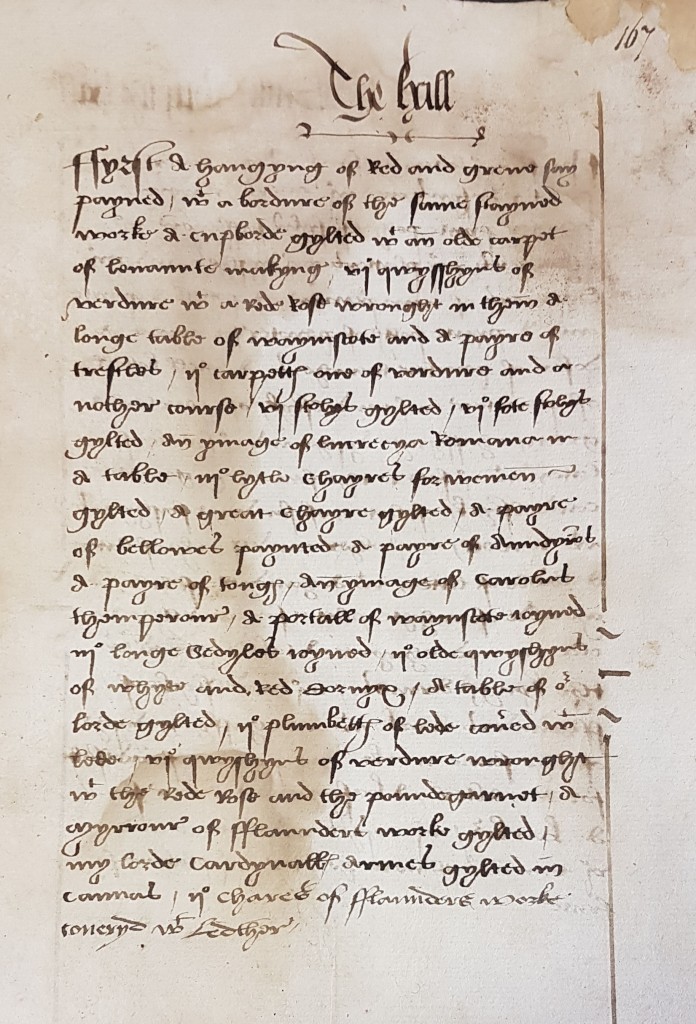

Fig. 4 Thomas Cromwell Inventory ‘Letters and Papers Foreign and Domestic, in the reign of Henry VIII’, vol IV part II: 1526-28 (1875), p,1456, The Hall.

Finally, and with no interior as such, yet containing very exact detail of an interior, is an extract of the inventory we hold of the hall in Thomas Cromwell’s house, in the Austin Friars, London. It is highly detailed and was commissioned by him, aiming to show his enormous wealth. This in itself is unusual, most inventories are taken after death to denote wealth; Thomas Cromwell himself wanted to know exactly how much he was worth during his life. This inventory was used extensively by Hilary Mantel for her research while writing Wolf Hall and again for the television adaptation of her book. It was this document that enabled the interiors of Cromwell’s house to be reproduced with such accuracy.

Sally Hoult is a Reader Adviser at the National Archives, advising readers both in the reading room and remotely with their research, her job also entails providing document displays to visiting guests of the National Archives. Sally has recently moved from the Modern Overseas Knowledge team to the Design Photography and Art Collections Team. She studied for a Dip AD at Hornsey Art College and 17th & 18th century decorative arts at Sotheby’s. Sally enjoys painting, particularly portraits in her spare time.

Comments

Very interesting blog Sally. I would never have thought to use central government archives for the history of interior design !