Excavating the work of Eveleen Myers. The Rediscovery of a late Victorian Photographer, by Judy Oberhausen and Dr Nic Peeters

![Silvia Constance Myers and Leopold Hamilton Myers by Eveleen Myers (née Tennant) [the sitters' mother], platinum print, c.1890 © National Portrait Gallery, London](https://www.britishportraits.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/mw150347.jpg)

Silvia Constance Myers and Leopold Hamilton Myers by Eveleen Myers (née Tennant) [the sitters' mother], platinum print, c.1890 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Judy Oberhausen first met Eveleen Myers (née Tennant, 1856-1937) many years ago at the Delaware Art Museum when she was a young intern working with the Bancroft Collection of Pre-Raphaelite Art. George Frederic Watts’s portrait of Myers as the fresh-faced Jessamine is still there in a gallery filled with other famous Pre-Raphaelite beauties – although they are fewer in number these days. Judy’s second encounter with Myers happened when she saw John Millais’s stunning portrait of her as Miss Eveleen Tennant at the Tate Gallery (now Tate Britain) in London. Little did Judy know at the time how these portrayals of youthful beauty had helped to determine Myers’s destiny.

The Millais painting caused a sensation at the Royal Academy in 1875 and its subsequent reproduction in the popular press would launch the young Eveleen Tennant into Victorian society and its heady art world. Indeed, upon seeing the painting, scholar Frederic Myers exclaimed to George Eliot: ‘I have fallen in love with the girl in that picture.’ In 1879 when the couple married, her mother Gertrude Tennant’s ambition in commissioning the portrait from Millais was fulfilled. For most young Victorian matrons this would have been the end of the story. But, fortunately for Eveleen, it was just the beginning. For Judy Oberhausen this second meeting would prove to be the start of a re-acquaintance with the woman in those two paintings.

Taking up photography after the birth of her three children provided Eveleen Myers with a far richer life than Judy had imagined. And so, coming across a few reproductions of her photographs by chance just after seeing the Millais portrait, Judy learned that the young model had become a well-respected photographer in her own era. Since information on Myers seemed a bit scarce, it was time for Judy Oberhausen to enlist her intrepid Belgian writing partner, Dr Nic Peeters, in a new research adventure.

Judy and Nic firmly believe that art historians are really just archaeologists who prefer white gloves to trowels. Hence, in 2013, they began an expedition to excavate the career of Eveleen Myers. As researchers they have been very fortunate with the maps provided to them by David Waller and Trevor Hamilton, who have written biographies of her mother Gertrude Tennant and her husband Frederic Myers. Both authors pointed the way to abundant visual and archival sources in London, Cambridge, Wales and Belgium. Judy and Nic were also delighted to find that Welsh writer Helen Papworth was engaged in research on Dorothy and Henry M. Stanley, Myers’s sister and brother-in-law, and was very generous in exchanging notes on the Tennant family.

Their quest began in London at the National Portrait Gallery which owns the bulk of Eveleen Myers’s work and has digitized many of the images and published them online. On his first visit there, Nic soon found that Photographs Cataloguer Constantia Nicolaides and former Curator of Photographs Terence Pepper were already fans of Eveleen and only too happy to answer questions regarding the collection. The NPG holdings comprise over 200 photographs mostly in large format albums many of which are not included on the gallery’s website. Every scholar knows the thrill of discovery that comes with encountering an artist’s work in person – pouring through the actual photographs, many of which are inscribed, was particularly satisfying. What grew to be obvious to Oberhausen and Peeters during this process was how increasingly self-assured Myers became as she continued to produce images.

Leonora Piper, medium, by Eveleen Myers (née Tennant), platinum print, 1890 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Taking up photography in the late 1880s when she was in her mid-thirties, it is remarkable how quickly Myers grasped the technical and expressive complexities of the medium. Initially using her children as models, she quickly moved on to portraiture of Victorian celebrities. Her portraiture style progressed rapidly from idealistic Pre-Raphaelite images of children (top) and women (above) to a more modern and unsentimental depiction of the great and the good such as the Right Honourable William Ewart Gladstone (below) and educator/feminist Anne Jemima Clough. Of particular interest were Myers’s sharp focus images of costumed women that bear a startling resemblance to silent movie stills.

William Ewart Gladstone, Prime Minister and writer, by Eveleen Myers (née Tennant), platinum print, 25 April 1890 © National Portrait Gallery, London

![Anne Jemima Clough by Eveleen Myers, platinum print, 1890 Copyright © The British Library Board [Add. MS 72824B f.6]](https://www.britishportraits.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/publiceye3lge.jpg)

Anne Jemima Clough by Eveleen Myers, platinum print, 1890 Copyright © The British Library Board [Add. MS 72824B f.6]

The plethora of family papers has been a boon to this project. The ‘Henry M. Stanley Papers’, property of the King Baudouin Foundation, held in trust at the Royal Museum of Central Africa in Tervuren near Brussels, Belgium and the West Glamorgan Archive Services in Swansea, Wales contain much information on family matters. Of great importance to understanding the social and artistic milieux in which Eveleen and her sister Dorothy ‘Dolly’ Tennant (later Lady Stanley) were raised are Dolly’s voluminous diaries. Because she was such a prodigious diarist, one learns the details of both sisters’ immersion in the Victorian art world of the late 1870s. Strong and lasting friendships with artists such as Watts, Millais and Edward Burne-Jones provided them with an art education accessible to few women of their time. For Eveleen her experiences as a model and friend of such pre-eminent artists had a profound effect. She learned lessons in patience, craft, and the consummate professionalism that was required of a successful portraitist.

Oberhausen and Peeters’s most extensive expedition for the Myers adventure so far was their March 2013 visit to the ‘Frederic Myers Papers’ at the Wren Library (Trinity College, Cambridge). This research trip was kindly funded by an award they had received from the Paul Mellon Centre in London. For five days Judy and Nic huddled in the Wren’s magnificent but bitterly cold seventeenth-century reading room (‘Sir Christopher didn’t believe in central heating’, they were cheerfully told upon registration.) The archival material – mainly letters written by Eveleen and Frederic Myers – provided documentation of how Eveleen discovered her talent as a photographer and how she developed her practice. It shows her growing excitement at getting her first camera and setting up her darkroom; her informal tutelage under Albert George Dew-Smith, a Cambridge photographer; her solicitation of models and prominent sitters; her exhibition of her works in London; and her desire to sell her works abroad in the US.

Although sometimes difficult to decipher – Eveleen did not bother much with either correct spelling or punctuation – the personal papers of the Myers couple quickly transported Oberhausen and Peeters back to late nineteenth-century Cambridge and London where they read of the couple’s life together and apart. Leckhampton, their Cambridge home, was bohemian by any standards. Having been trained as a classicist, Frederic Myers was a Fellow at Cambridge until 1874 when he became an inspector of schools for the area and also became deeply involved in psychical research. He was frequently away from home on school business and when he was at home the house became a hub for séances and other paranormal experiments. It is clear that the family felt his absences keenly but we see how Eveleen’s photographic practice became a fun and collaborative outlet for herself and her children. Her photo sessions with such eminent Victorians as William Ewart Gladstone are recalled with great hilarity by her sister Dolly.

Likewise when famous mediums visited Leckhampton, Eveleen used her powers of persuasion to enlist them as models. She also made periodic trips to her mother’s home in Westminster to meet with sitters who frequented Gertrude Tennant’s salon gatherings. Thus, Judy and Nic came away from Cambridge with an intimate view of Eveleen Myers’s career and life during the 1880s and 1890s.

As contemporary art historians living in the age of the internet much of Judy and Nic’s preliminary inquiries and a good deal of their archival research were aided by technology which gave them access to books, periodicals, finding aids, digitised images and correspondence. Hence, archival research was supplemented by web research that disclosed details about Myers’s exhibition history, publication of her work in periodicals, critical appraisal of her work, the identity of her less prominent sitters (ancestry.com was particularly useful here) and details of the only interview she ever granted. Thanks to this interview, for The Woman At Home magazine, Oberhausen and Peeters learned how as a young girl Myers was taken by Gertrude to meet the famous photographer Julia Margaret Cameron in her studio. Many years later she vividly recalled this transformative experience to interviewer Marie A. Belloc. She also spoke eloquently about many technical as well as artistic aspects of her work and the challenges of her career as a portraitist.

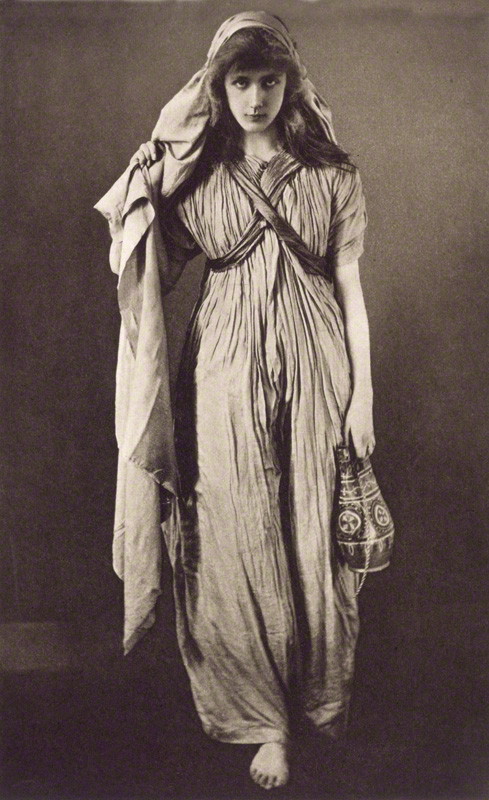

Unknown model dressed as ‘Rebecca’ by Eveleen Myers (née Tennant), sepia photogravure, 1891 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Why do Oberhausen and Peeters employ this ‘archaeological’ methodology? The answer is because they want to acquire an intimate view of their subject’s career and life that is not ‘contaminated’ by twenty-first-century thinking. Hence, they approach their primary sources with caution, like an archaeologist. And they peel them back layer by layer. Also like an archaeologist, they attempt to learn as much as possible about the context in which their subject created her art. To this end they enlist the services of anyone, from any discipline or field, who can help them to obtain the necessary information.

In spite of Judy and Nic’s extensive research, a mystery remains about Eveleen Myers. This makes her even more interesting and significantly demands further research into her career and life. Judy and Nic are still trying to figure out why Eveleen Myers, after the death of her husband Frederic in 1901, seems to have abruptly abandoned her darkroom and photographic practice in Cambridge. She spent much time in London at her mother’s home and was involved with the editing of Frederic Myers’s writing and autobiography. Like many widows of ‘great men’ she became the keeper of the flame of his reputation instead of continuing to function as a creative artist herself. She seems to have returned to Cambridge in 1914 to take some nostalgic shots of her beloved Leckhampton but for the rest of her life she remained silent on photography. Perhaps further research will uncover the reason why after having nurtured her creative skills as a photographer with such enthusiasm for over ten years she ceased so abruptly.

As art historians, Oberhausen and Peeters feel that through their continuing study of Myers’s work they have become better qualified to assess her contribution to nineteenth-century photography. For them she has become a transitional figure between the early Pre-Raphaelite phase of pictorial photography and its later more modern phase. It is important to note that Oberhausen and Peeters opt to use the term ‘pictorial photography’ the way Susan Sontag uses it in her seminal collection of essays On Photography (1977): as the opposite of ‘documentary photography’. According to Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary the word pictorial means: “of or relating to a painter, a painting, or the painting or drawing of pictures”. Its origin is the Late Latin pictorius and the Latin pictor, meaning painter. Hence, practitioners of pictorial photography tried to emulate fine art. They did so by applying the formal conventions of painting to photography’s naturalistic and/or literary subject matter.

As their research progresses, the story of Eveleen Myers’s life and career continues to reveal itself most intriguingly. Judy and Nic hope to report about their recent findings in the near future. An essay about Myers’s life and work and her role in the development of photography (including an extensive bibliography and several representative illustrations) has been accepted by the British Art Journal. It is set to be published before the end of 2015.

Comments

Results of our research into Eveleen Myers were published in the British Art Journal: ‘Eveleen Myers (1856-1937): Portraying Beauty. The Rediscovery of a Late-Victorian Aesthetic Photographer.’ British Art Journal, vol. 17, no. 1, Spring 2016, pp. 94-102.