Portraits in context at Weston Park by Emma Nock

Our tour of the house began in the Breakfast Room, with its impressive collection of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century portraits. Image by Emma Nock.

As somebody whose own specialism is not actually in art history (but rather in historic houses and other buildings), I was very keen to attend the portrait study day at Weston Park, not only to enjoy privileged access to the house and collections, but also to benefit from the in-depth knowledge of their curator—Gareth Williams—and my fellow delegates.

As a curator with the National Trust in the South West region, my own current role is a twelve-month research project to review the history and management of both house and collections at one of the Trust’s absolute treasure houses, Kingston Lacy in Dorset. Though quite distant geographically, Kingston Lacy has some notable parallels with Weston Park: both houses were originally built in the Restoration period, and both have impressive indigenous collections of art, including portraits by major figures such as Lely and Van Dyck. The day did not disappoint, and, in the relaxed atmosphere, it was fascinating to listen to true experts discussing the finer details of issues such as attribution of paintings and the identities of their subjects.

The Drawing Room is enhanced by Lely’s portrait of Lady Wilbraham, for whom the Restoration house was built. Image by Emma Nock.

It was interesting to learn that many of the portraits by Lely still at Weston were bought from the sale held after the artist’s death, and seem to have been chosen primarily for their decorative potential to embellish the walls of Weston, rather than for any connection to the family. It was wonderful also to see that so many of the historic inventories for the house still survive, making it possible to trace the development of the collection and the changing picture hangs in the house down through the generations.

However, some of the aspects of the day that I found most thought-provoking from my own perspective related less to the individual portraits themselves than to the nature and challenges of their presentation within the country house setting. Here, it was interesting to contrast the issues and opportunities at independent properties like Weston Park and at National Trust properties.

One particularly absorbing discussion I had with fellow delegates concerned our shared sense that the house at Weston still retained very much the feeling of a family home, even though it has been in the care of the Weston Park Foundation since 1986, and now combines public access (as an Accredited Museum) with hosting conferences and other functions. Those of us who work with historic houses know how challenging is our aim of keeping these places “alive,” when the families now mostly live elsewhere, and the houses are primarily visited rather than lived in. Our ultimate conclusion at Weston was that it was precisely the fact that the house still has ongoing uses—hosting events and offering people the chance to linger in the formal rooms and even to stay overnight in the bedrooms once occupied by the family and their guests—that give it this palpable vitality.

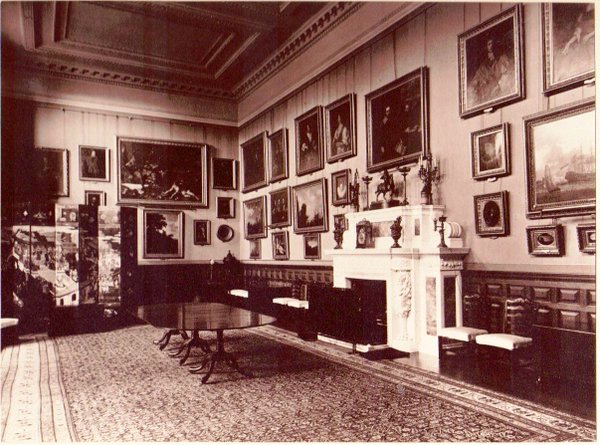

An archive image of the dining room at Weston Park c.1890 shows a busier, less ordered picture hang than is seen today. Image: Weston Park.

For me, it was also noteworthy that Weston is emphatically not a house where time stands still. At Kingston Lacy, many of the schemes of decoration and furnishings, including a number of the picture hangs, still reflect the intentions and alterations of the house’s most creative owner and avid collector, William John Bankes, in the mid-nineteenth century, and few changes were made after the Edwardian period. In contrast, at Weston, the Bridgeman family continued to introduce entirely new decorative schemes, notably in the 1930s and 1960s. Many of the picture hangs therefore also date from this later period. As such, there is a precedent for ongoing change, and a potential for flexibility which often simply does not seem possible at many other historic houses. For Weston’s curator, this must at times offer an unusual degree of freedom, but also a significant burden of responsibility when making the decisions about proposed changes or interventions.

The dining room in more recent years, showing the extent of the family’s twentieth-century alterations to both decoration and picture hang. Image: Weston Park.

One respect in which Weston is very much up-to-date is with regard to the lighting of the paintings. Gareth explained that the family had introduced picture lights in a number of rooms in the 1960s, but that the old lights were unsatisfactory in a number of respects, including high energy use and the potential for UV light damage to the paintings. The most recent solution has been a room-by-room phased replacement with LED picture lights, which, besides being safe and energy efficient, provide a soft, even wash of light over the whole canvas, which, in some cases in particular, really enhances the beautifully rendered skin tones of the portraits’ subjects. Once again, it is the choices and changes made in the past by the family, when initially opting to install picture lights, which have enabled this use of the most modern technology now, to enhance our appreciation of some of the portraits at Weston. In rooms where no such lighting existed, a conventional conservation approach is being taken, and, for example, no new installation is proposed in the Breakfast Room, where the hang includes sixteenth- and seventeenth-century portraits from the Newport family’s core collection.

The even pool of light cast by the modern LED picture lights is flattering to the subjects of the portraits, in this case Viscountess Torrington, by Gainsborough. Image: T M Lighting Ltd www.tmlighting.com

The Bridgeman family’s introduction of picture lights also echoed for me one of the issues that is currently very much at the forefront of my work at Kingston Lacy: when a house contains such significant works of art, should our aim be to “do justice” to the individual paintings, to display them to the very utmost of our ability (an attitude that certainly prevailed for many specialists in the past). Alternatively, should our aim be instead to respect the composite appearance and atmosphere of the family homes: to preserve the overall balance and impact of the collections and interiors and to avoid major interventions? Or, is it ever really possible to strike a satisfactory compromise between these two extremes, and can the spirit of a place endure even when the details are changed? These are issues with which we must all continue to grapple, and, for me, the study day at Weston Park offered a most valuable chance to see things from the slightly different perspective of a remarkable independent historic house, in which everyday life continues, and change is ongoing, but the spirit of the family house undoubtedly lives on.