The Lithotomist’s Art – a slice of surgical history in portraiture and engraving by Lucy Peter

Edward Nourse the elder (d.1738), surgeon, attributed to Joseph Highmore (1692-1780). © 2009 The Royal College of Surgeons of England

Over the past few years I have become increasingly interested in the history of medicine, in particular, the point at which it intersects with the art world. I was therefore delighted to be offered a place on the recent study day organised by Understanding British Portraiture focusing on Healthcare and Medical Portraits across London’s greatest medical art collections.

For me, the most fascinating and unexpected discovery of the day was a portrait by Joseph Highmore of Edward Nourse holding what appears to be an egg-shaped pebble (left). This pebble, it rather bizarrely transpired, is in fact a bladder stone. Intrigued as to why Nourse should wish to be pictured with such a specimen, I followed up the study day with a trip to the Wellcome Library (a brilliant resource for the incurably curious) with two key questions: why did Highmore depict Nourse with a bladder stone and are there any other examples of ‘stones’ represented in portraits?

One of the first things I discovered was that the practice of removing bladder, gall and kidney stones, has a long history. Awareness and diagnoses of these troublesome stones dates back thousands of years and many famous names, including Caesar Augustus, George IV, Samuel Pepys and Oliver Cromwell appear on the list of sufferers.

Lithotomy, the process of removing bladder stones, is one of the oldest, recorded surgical procedures. Hippocrates mentions it in the 4th century BC, advising physicians never to attempt to remove stones but, rather to ‘withdraw in favour of such men as are engaged in this work.’ This division between the physician and the professional ‘lithotomist’ continued into the Middle Ages when travelling lithotomists would move from town to town performing lithotomies on special, portable tables.

The traditional method for removing stones is known as ‘perineal lithotomy’ and involves cutting down on the base of the bladder through the perineum so that the stone can be extracted using forceps. In order to access the stone, the patient must lie on his back, thighs lifted high and heels drawn back towards the buttocks. Without anaesthetic, the operation was unimaginably painful and would often require the assistance of four men to hold the patient in place.

‘Ortus sanitatis: stones, bladder-stone’, from ‘Ortus sanitatis’ published by Jacob Meydenbach, Mainz, 1491.

Wellcome Library, London

Given the long history of lithotomy, it is not surprising to find that Nourse is not the only surgeon to have been depicted holding a bladder stone. One of the earliest images I came across of a surgeon with a stone is taken from a leaf of Jacob Meydenbach’s Ortus sanitatis (1491) (above), a popular compendium of medical, plant and herb lore (above). The operation is clearly crude but certainly attests to both the longevity of the procedure within the history of surgery and, possibly, the existence of ‘travelling’ lithotomists (is that a pair of wheels in the foreground?).

Jan de Doot by Carel van Savoyen (1619-65), oil on canvas, c1650-60.

University of Leiden, image from Wikimedia Commons

Carel de Savoyen records perhaps one of the best known stories involving a bladder stone in his portrait of the Dutch blacksmith Jan de Doot (right). According to Nicolaes Tulp in Observationes medicae, Jan de Doot performed a successful lithotomy on himself in 1651. With only his brother to assist him, Doot cut through his own perineum with a kitchen knife and extracted the offending stone with his fingers(!!). The portrait painted four years later, depicts Doot with the knife in one hand and an egg-sized stone, set in gold, in the other.

The significance of the stone in Highmore’s portrait of Nourse would appear to relate to a very specific medical scandal involving Edward Nourse and the bladder of a Mr Gardiner. At the time this likeness was taken, Edward Nourse was practising as a surgeon at St Bartholomew’s hospital in London. In 1738, a Mrs Joanna Stephens devised a remedy for ‘the gravel’ that she claimed could dissolve stones in the bladder without the need for surgical intervention. To see if the remedy worked, a parliamentary committee was set up to supervise a clinical trial. Four patients were put on a course of Mrs Stephens’ treatment and, when all reported relief of their symptoms, the treatment was generally accepted and Mrs Stephens was presented with a £5000 reward.

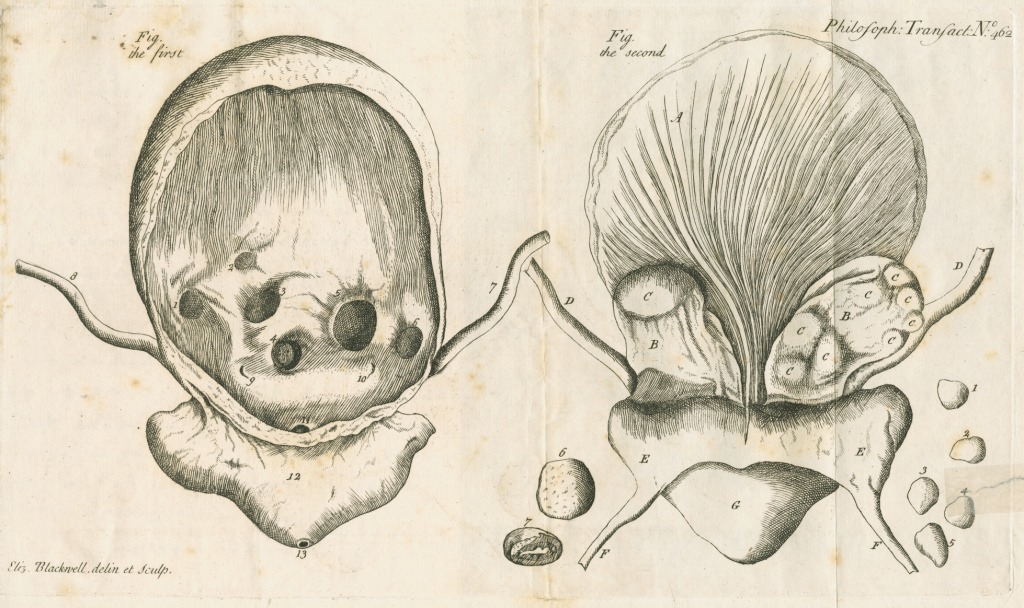

Sceptical of Mrs Stephens’ claims, Nourse decided to do his own independent tests on one of the guinea pigs, a Mr Gardiner. Nourse examined his patient before, during and after his treatment and, when Mr Gardiner died on 2 January 1742, did a public autopsy of his bladder. On discovering six holes and nine stones in Mr Gardiner’s bladder, Nourse wrote a concerned letter to the Royal Society in 1742. The letter was accompanied by a full report and Mr Gardiner’s actual bladder. The bladder was later recorded in a drawing by Elizabeth Blackwell (below) and, I would suggest, the stone immortalised in Highmore’s portrait.

Human bladder and bladder stones by Elizabeth Blackwell (1700-1774), engraving, 1742.

© The Royal Society

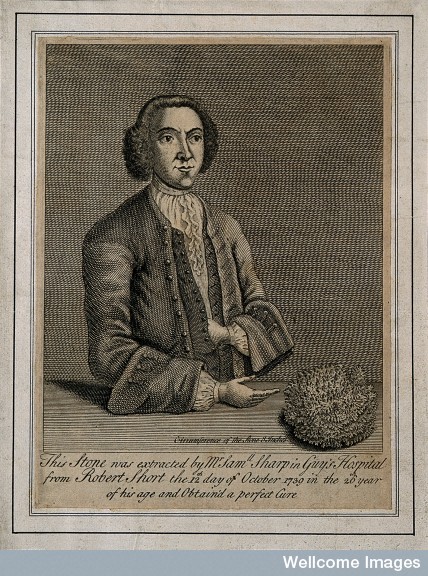

One of the most surprising things I came across in my search for portraits of stones was a number of what appear to be post-operative portraits in which patients, rather than surgeons, look to have been depicted alongside their own stones. In one particular engraving, a sitter, Robert Short, appears alongside a huge, fibrous calculus (below). According to the inscription, the stone removed from Short’s bladder measured eight inches in circumference – although the stone actually depicted is significantly larger. The fact that the inscription refers to the patient having obtained a ‘perfect cure’ might suggest that the portrait was a form of propaganda for surgeons hoping to secure new patients.

Robert Short, who had a bladder-stone removed which was eight inches in circumference, engraving, c.1740.

Wellcome Library, London

I fear that this post is but a very small ‘slice’ of a much larger discussion. However, I very much hope that this discussion continues…