The Portraits of Leon Underwood by Simon Martin

Leon Underwood © Estate of Leon Underwood and the Redfern Gallery, London

It is over forty-five years on since the last major museum retrospective of the work of Leon Underwood in 1969. Although Underwood (1890-1975) has been described as ‘the precursor of modern sculpture in Britain’ he is an overlooked figure in the history of Modern Art. Between the 1920s and 1950s he created an innovative body of figurative sculptures that were informed by his appreciation of non-western art, in particular from Africa and Mexico. As is revealed in the long overdue retrospective at Pallant House Gallery this Spring, throughout his career Underwood was concerned with the representation of the human form, eschewing abstraction. But he also produced some penetrating portraits and self-portraits which punctuate his fascinating career.

Following the First World War Underwood was commissioned to paint a portrait of Captain GB McLean, a Canadian war hero and recipient of the Victoria Cross. In the painting the soldier’s tightly clenched fist suggests that he had not yet come to terms with his wartime experiences. Yet the formality of such works is in marked contrast with much of Underwood’s subsequent work, such as the lively brushstrokes of his portrait of Charles Ashurst (1922) which reflect the teaching at Underwood’s Brook Green School, where he encouraged students to work fast in order to capture the effects of volume and movement. In Venus in Kensington Gardens (1921) Underwood updated the Impressionist imagery of Manet and Renoir to present his model Kitty Malone seated nude surrounded by his friends and family in a London park tearoom. The artist Clement Cowles who is seated in the painting reappears in the same pose in a 1922 portrait etching, albeit playing draughts.

Venus in Kensington Gardens by Leon Underwood, 1921 © Estate of Leon Underwood and the Redfern Gallery, London

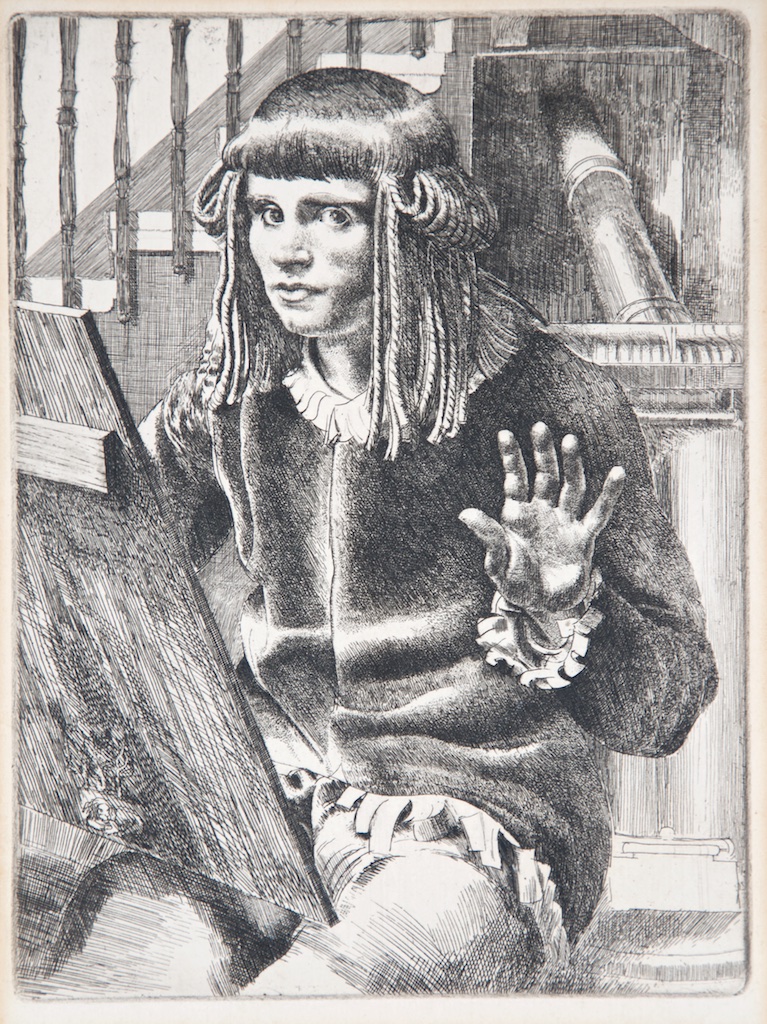

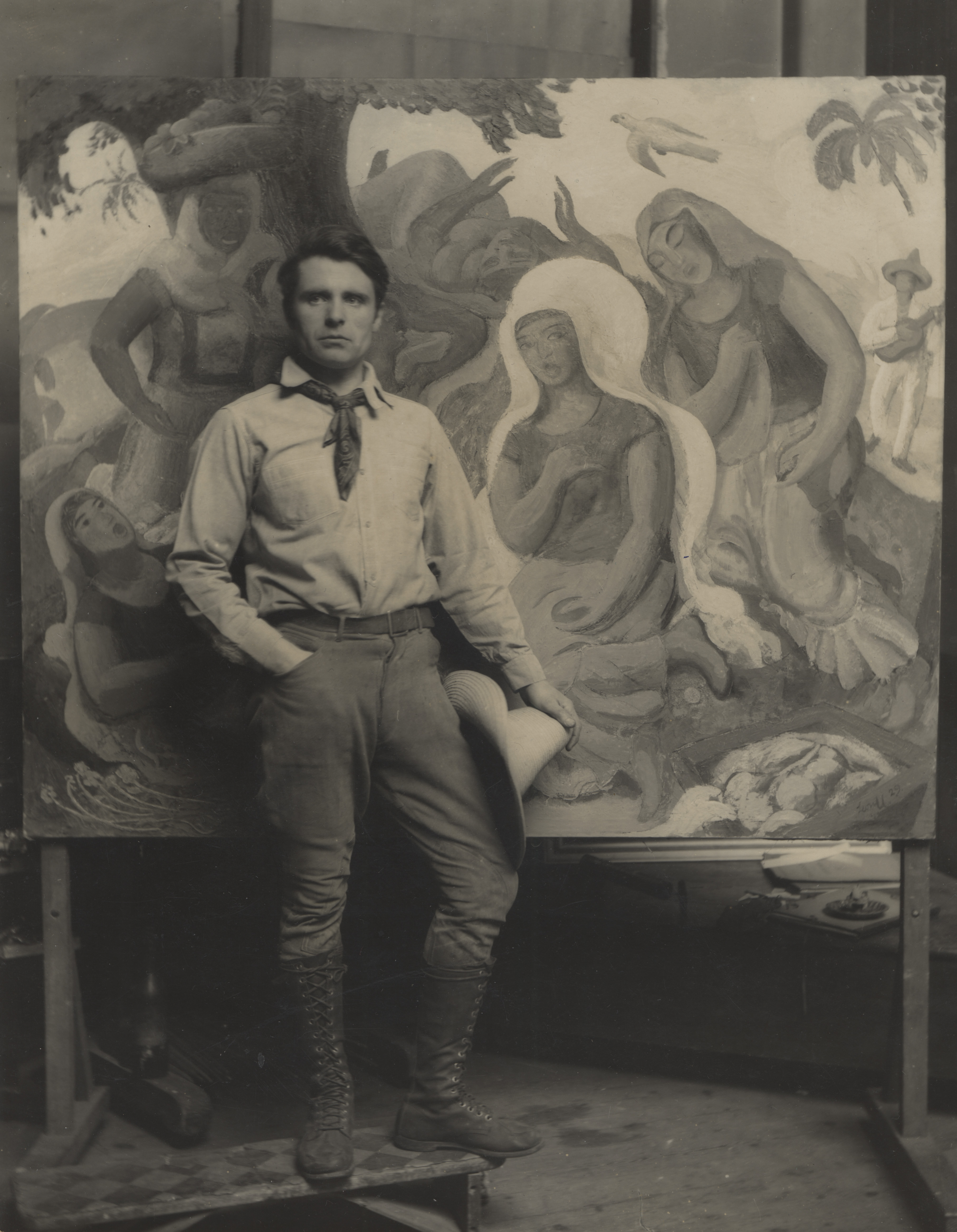

Underwood’s early portrait etchings were rooted in tradition: some such as The Egg Seller (1922) and Granny Ashdown (1922) have the intensity of Rembrandt and Dürer. The artist’s father had run a print dealership in London and before his training at the Regent Polytechnic and the Royal College of Art Underwood had copied antique prints. In one etching Underwood depicted his student Eileen Agar seated at an easel, whilst the Indian printmaker Mukul Dey was the subject of another, resolutely staring ahead at the viewer. Underwood was a radical force in British art education, and in addition to Agar students at the Brook Green School which he established in 1921 included Gertrude Hermes, Blair Hughes-Stanton and Henry Moore, amongst many others. His students were encouraged to approach life drawing with expressive freedom and innovate with printmaking mediums such as wood engraving. Amongst his early etchings are two remarkable self-portraits: one shows the artist seated in a landscape gazing holding the viewer’s eye as he grips his drawing board with determination. In another, the artist is wearing a long wig – not so much an early anticipation of Grayson Perry transvestism, but a theatrical self-presentation in one of the outfits from the flamboyant fancy dress parties Underwood organised at the school (below). He was clearly a great manipulator of his own public identity: at the entrance to the exhibition is a photograph of him in a dapper bow tie posing before the silhouette of one of his rhythmic bronzes, in another photograph we see him posing as a dashing adventurer following a trip to Mexico.

As Underwood developed his career as a sculptor during the 1920s, he ceased to make etchings and instead produced relief wood engravings. These have an expressionist angularity that is influenced by his appreciation of tribal art, as in Caesar’s Icon (1925) a witty comment on the perils of portraiture for an artist, in which the sculptor is held slave to the vanity of their sitter. The sculptor carves the face of the Caesar / Pharaoh, even as he is held captive, suggesting the need for a flattering likeness. After his trip to Mexico in 1928 Underwood was to create imaginary portraits of the Aztec leader Montezuma II and Hernán Cortéz, the Spanish Conquistador who led the expeditions that led to the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought much of Mexico under the rule of the King of Castille in the 16th century. Underwood depicts Cortéz holding a stone heart, before a broken temple, with the feet of a dead Inca in the background to make a comment on the impact of colonialism, whilst Montezuma is portrayed as ‘a noble savage’. In marked contrast to his portrayals of these historic figures is Underwood’s 1937 bronze bust of King George VI, lent by the National Portrait Gallery (below). Indeed it began as portrait of the King’s brother Edward VIII, but after the abdication in December 1936 Underwood altered the identity. To convey the King’s regalia of the Order of the Garter without interrupting the simplicity of the figure Underwood chased the designs into the bronze. When it went on show at the Fine Art Society in May 1937 to coincide with the coronation Buckingham Palace discreetly requested that this unofficial portrait was withdrawn from view. Exhibited in the context of his other rhythmic bronzes of dancers and musicians it seems far more formal, but as a royal portrait bust is remarkably modern. It is the work of an artist who was aware of the traditions of art, not just in Western Europe but from around the world, and determined to draw on these to push forward his own distinctive and idiosyncratic modernity.

Further details on the exhibition Leon Underwood: Figure and Rhythm on the Pallant House website here >>

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester 7 March – 14 June 2015