Tradescant the Younger returns to Lambeth by Emily Fuggle

Portrait miniature of John Tradescant the younger by unknown artist, oil on silver, late seventeenth century. Bought with the assistance of the Art Fund, the Beecroft Trust and private donations © The Garden Museum

When I joined the Garden Museum in April last year, one of our most recent acquisitions was still in store, purchased just several months earlier. It is a remarkable object for the Museum to have in its collection, as well as one of my own personal favourites. It is a small portrait oil on silver of John Tradescant the Younger (1608-1662), the plant hunter, gardener and collector, who was buried, along with his equally renowned father, also John, in a tomb in the graveyard of St-Mary-at-Lambeth church, the home of the Garden Museum.

The story of the John Tradescants and in particular, their Ark or cabinet of curiosities, had intrigued me for quite a while previously. Visitors to their seventeenth century museum (the first public museum in England) could pay sixpence to see their large collection of intriguing ‘rarities’, which included Powhatan’s mantle (Powhatan was the father of Pocohontas), Henry VIII’s hawking glove and hawk’s hood, Henry VI’s cradle and other objects demonstrating feats of technical skill, of ritual interest, or the ‘curious’. The vivid stories of this and similar cabinets seen across Europe at this time had captured my imagination and interest since I was a postgraduate student at UCL. I wanted to learn more about them, and the new role at the Garden Museum, working on a recreation of the Tradescant Ark for a Heritage Lottery Fund application, seemed like a great opportunity. A trip to India before taking up my new post gave me time to read Strange Blooms, Jennifer Potter’s wonderful book bringing the Tradescant story to life. Since then, the past year has seen me more and more immersed in their story – whether thinking up ideas with our exhibition designers, visiting other cabinets of curiosities, such as the Bargrave collection at Canterbury, or explaining the Tradescants’ adventures to our visitors.

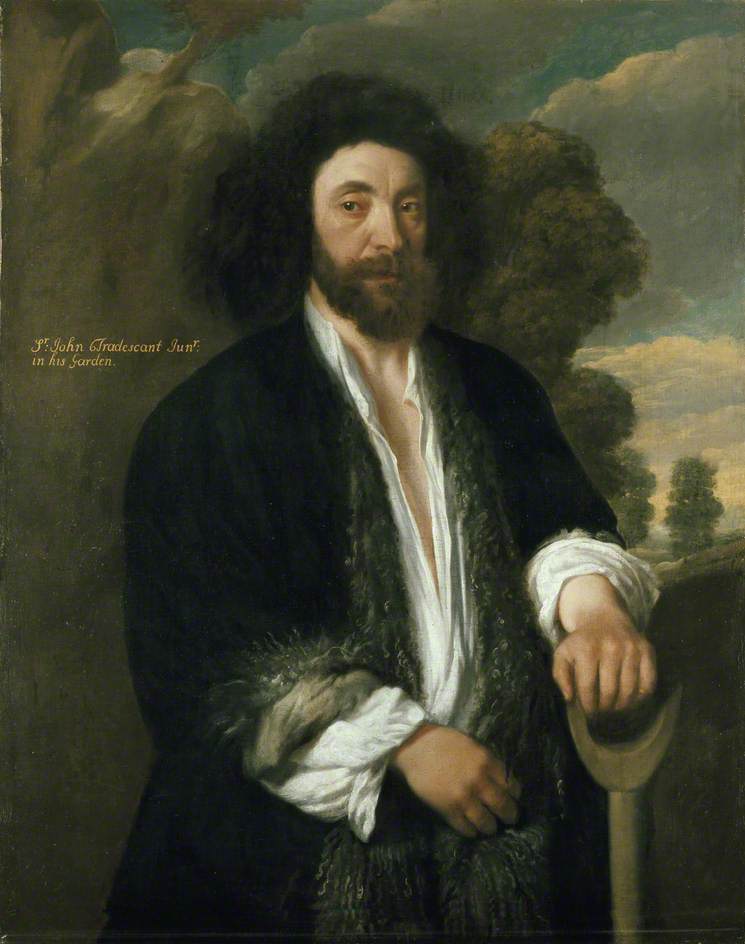

John Tradescant the Younger as a Gardener, attributed to Thomas de Critz (1607 – 1653) © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

This portrait is a copy of a painting attributed to Thomas De Critz (1607-1653) in the Ashmolean Museum. Who painted this small portrait, and why, we do not know for certain. Silver was comparatively rare as a medium for English portrait miniatures during this period, and so it has been suggested that it was commissioned by Hester Tradescant, John’s wife, to be carried rather as a precious token, a locket. Painting on metal was more commonly seen on the continent than among English portrait painters – but we haven’t yet been able to identify a possible artist. The only Englishman known to have been painting miniatures on silver, rather than the more common vellum on card, was Cornelius Johnson – but his style is quite different. Likewise, Hester’s kinsman, the painter Cornelius de Neve has also been discounted – he had a very different technique too.

John Tradescant the Elder, attributed to Thomas de Critz (1607 – 1653) © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

In our small portrait, John Tradescant chose to identify himself with his profession – he is shown dressed in the open shirt (and in the larger painting, too, holding a spade) clearly represented as a gardener rather than as a gentleman, which the reputation of his family had by that time entitled him. The Tradescants travelled the globe collecting plants – Tradescant the Younger visited Virginia and the ‘New World’, bringing back new varieties such as the tulip tree, the American plane tree and the Virginia creeper to Britain. Some of his plants are described and recorded in contemporary herbals by botanists, such as John Parkinson, who knew the two gardeners well..

Tradescant the Younger died in 1662 and after Hester Tradescant was found drowned in her garden pond, the Tradescants’ neighbour, the ‘wily’ lawyer Elias Ashmole, who had helped catalogue their collection, inherited it. He bequeathed it to the University of Oxford, where the museum was begun in his own name. Elias Ashmole too is buried in the Garden Museum church.

Hester Tradescant and her stepson John, attributed to Thomas de Critz (1607 – 1653), 1645 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

The Tradescants’ legacy today includes the Garden Museum, set up when the then derelict church of St-Mary-at-Lambeth was saved from demolition by Rosemary Nicholson, a Tradescant aficionado, who had come hunting for their tomb. The graveyard where the Tradescant tomb can be found is now a knot garden, designed by Lady Salisbury, with planting reflecting the era of the Tradescants and the new species they discovered. Many writers have been inspired by the Tradescant story and their collection too – Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) wrote in Alice in Wonderland about the dodo, which we had seen in the Oxford Museum of Natural History; Philippa Gregory authored two historical novels based on the Tradescants’ lives, and we are now working here to re-curate the Ark as a new permanent exhibition at the Garden Museum using objects kindly loaned by the Ashmolean Museum.

A passage from Philippa Gregory’s Virgin Earth brings their adventures to life, here John and Hester are in the garden of their Lambeth home:

‘Before them the great branches of the chestnut avenue bobbed, their upwinging boughs carrying the hidden sweet spikes of their buds, their proud, broad trunks strong and still. In the orangery, safe in the warmth, were the rare and tender plants, the exotic, precious plants which the Tradescants, father and son, had brought from all over the world for the gardeners of England to love. ‘We will be forgotten,’ John whispered.

Hester leaned back… ’Oh no, they will remember you,’ she said. ‘I think the gardeners of England will remember you with gratitude one hundred, two hundred, even three hundred years from now, and every park in England will have one of our horse chestnut trees and ever garden one of our flowers.’’

And as Philippa Gregory well knew, the story of the Tradescants does continue to remembered even four hundred years after the John Tradescants, seventeenth century plant hunters, gardeners and collectors once lived.