Tudor & Jacobean Workshop, 4 December 2009

The Tudor & Jacobean workshop was held in the Painters’ Hall on Friday 4 December 2009. Below are synopses of some of the presentations.

Tudor & Jacobean Workshop programme

Tudor & Jacobean Workshop speakers

Robert Tittler, Distinguished Professor of History Emeritus, Concordia University, Montreal, Canada

Portraits and painters in provincial England: an archival approach

This presentation was intended to provide a ‘starter’s kit’ for investigating the identity of patrons and painters, especially in provincial England, through the use of archival sources. It presented such sources as wills, household inventories, correspondence, household accounts, heraldic visitations, and guild records, and suggested how to find them. A handout describing particular resources were distributed on the day, and can be downloaded here (PDF): Archival Sources handout

Jenny Tiramani, Theatre Designer and Dress Historian

Waistcoats, Partlets, Foreparts and Petticoats: Interpreting Multi-Layered Clothing in Early Modern Portraits

Surviving garments provide the vital evidence needed to gain an understanding of the clothing worn in portraiture of this period. Often garments can only be partially seen in these images and similar surviving garments can help uncover the true nature of those shown. The bodice shown left, with its three-dimensional embroidery in detached buttonhole stitch, has a plain linen back as it was intended to be worn with a gown over it (in the same way as the one in the portrait shown top left). This was a practical solution, made not only to save the expense of the metal thread decoration where it would not be seen, but also to avoid discomfort to the wearer of the thick bulky embroidery that would have spoilt the smooth shape of the fitted gown at the back.

Caroline Jeeves, National Trust Learning Officer, Montacute House, Somerset

Portraits Find their Voice at Montacute House

Montacute House is owned by the National Trust, and a regional partnership has existed between the National Portrait Gallery and the National Trust since 1975. Over fifty Tudor and Jacobean portraits are displayed in the Long Gallery. Formalised Learning Programmes to facilitate engagement with the portrait collection were set up in 2003. Caroline’s presentation outlined how the portrait-related learning programmes at Montacute House have evolved and how the needs of different audiences are met. It included some of the successes, and lessons learnt, during the process of enabling portraits to ‘find their voice’ at Montacute House and facilitating active engagement with our visitors.

Christopher Rowell, Furniture Curator, National Trust

Some Observations on Furniture in Tudor and Jacobean Portraiture

King James I of England and VI of Scotland by Daniel Mytens, 1621 © National Portrait Gallery, London

This presentation pointed out that furniture in portraits – like costume, arms and armour, works of art, and other incidentals – is of considerable interest as a field of study. Usually ignored by picture cataloguers, and described (if at all) as a ‘chair’, ‘canopy’, ‘bed’, and so on, furniture is often accurately delineated by artists, sometimes minutely. This can be valuable to furniture and textile historians, especially in the case of early portraiture, because comparatively little European furniture survives before the second half of the 17th century.

Furniture at this early date often depended for its impact upon rich textiles (silks, velvets, and rich trimmings or passementerie fixed by decorative gilt nails), and many sitters chose to be portrayed wearing their best clothes and surrounded by grande-luxe objects. Court portraiture is especially given to the creation of an image of sophistication and splendour in which furniture (thrones, chairs, stools, cushions, oriental rugs, canopies) played an important role. In England, although little survives of the mise-en-scène of Tudor and Jacobean courts and private palaces, royal and aristocratic inventories and portraiture can reveal much, thus forming a more or less accurate picture of the surroundings and patronage of sitters in portraits.

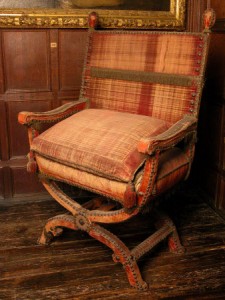

Some furniture types – such as the X-frame chair and stool – derive from Antiquity. X-frame furniture was a staple of royalty and authority from the earliest times (in China and Egypt as well as in Greece and Rome). Adopted by the Roman Catholic Church as a symbol of high ecclesiastical office, it is hardly surprising that Carolingian and later ruling dynasties revived the X-frame form. In Tudor and Jacobean portraits, both royalty and aristocracy are marked by the presence of an X-frame chair. One need only think of the series of full-lengths, formerly attributed to William Larkin (The Iveagh Bequest Kenwood). Such chairs today can only be seen at Knole, Kent (National Trust), and in the V&A (a single example used at the coronation of Charles II). They often were supplied with attendant stools and were set beneath canopies, to which the routine curtains in the background of portraits allude.

X-frame chair at Knole, Kent, c.1600-1620 (with Hampton Court inventory mark ‘1661’ underneath the seat, and therefore sometimes erroneously dated 1661) © National Trust / Jane Mucklow

The uniquely large collection of X-frame and other early 17th century furniture at Knole derives at least in part from the royal palaces (some seat furniture bears the inventory marks of Hampton Court and Whitehall Palace). It is therefore possible at Knole to gain a tangible sense of the lost interiors of Tudor and Jacobean England. The contents of the royal palaces are described minutely in the records of the Great Wardrobe (National Archives, Kew), and in other royal manuscripts. The bulk of expenditure went on textiles, some of which were imported from the Continent, and indeed Italian and French fashions were to the fore at least from the reign of Henry VIII. Seat frames were covered all over with textiles, or if not, often painted in decorative style to suggest patterned stuffs.

Sometimes a humble piece of furniture is depicted in an early portrait, but this is rare indeed given the emphasis upon rich textiles. Thus the full-length portrait of the 7th Earl of Northumberland (1568, Petworth House, National Trust) depicts him at prayer, kneeling at a humble oak joint stool, which supports a prayerbook. This Earl’s devotion to the Catholic Church and to Mary, Queen of Scots, was to cost him his head. Similarly, Holbein depicted Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s henchman, in his office sitting at a plain oak bench (National Portrait Gallery). This is an image out of A Man for All Seasons: he may well be portrayed at Hampton Court.

Table frames were usually of simple construction, but were covered by rich damasks, velvets or table carpets. Table covers in Spain were called sobremesas. An example was shown which was made as late as 1785-95 in the traditional style. This, and its pair, was made to accompany the richest of rich canopies and a neo-Classical throne for the throne room in the Palacio Real, Madrid, of Maria Luisa of Parma. Maria Luisa was the consort of Carlos IV, a considerable patron of neo-Classical furniture, and both monarchs were famously painted by Goya. Thus court furniture styles transcended fashion: the sobremesa – like the throne canopy – was a symbolic part of court ritual, and its form hardly changed in 250 years.

Clothes were much more important to royalties and aristocrats than they are today in the expression of rank, riches and power. Rich clothes demanded a rich setting. It is that concept that above all emanates from a study of the incidentals in Tudor and Jacobean portraits. Indeed, in the 1620s, when the flamboyant and spendthrift 3rd Earl of Dorset decided to update the furnishings of Knole, for once he economised by clearing out his wardrobe, and using the rich textiles as wall-hangings and chair covers.