Amy Marquis, Study Room Supervisor, The Graham Robertson Study Room, Department of Paintings, Drawings and Prints, The Fitzwilliam Museum

Scope of project

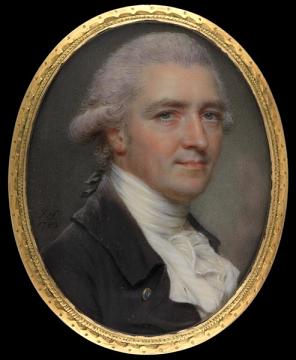

The Fitzwilliam Museum received a self-portrait by the esteemed miniature portrait painter, John Smart Snr (1741-1811) to be displayed alongside our already strong collection of miniatures by this artist as well as others. This provided a good opportunity to research the self-portrait, dated 1783, and situate it within the collection, looking at it in relation to other miniatures, self portraits, and portraits of others. This includes works from different periods, in different media and on a varying scale: from Peter Paillou’s portrait miniature of Susannah Wedgwood (1793) to Stanley Spencer’s large oil painting, Self-portrait with Patricia Preece (1937). The aim of this broad scope was to consider the notion of intimacy in portraiture (something so often associated with portrait miniatures) and how it connects these objects.

Daphne Foskett, Smart’s biographer, lists nine self-portraits by the artist, ranging in date from 1762 (recorded as a sketch in ‘crayons’) to one made the year before his death in 1811. The archives at the Witt and Heinz libraries revealed that the portrait the Fitzwilliam has on loan was sold at Sotheby’s on 28 June 1935, not as a self-portrait, but with the name, William Rankin Allen attached to it. Arthur Jaffé bought the miniature and identified it as a self-portrait. Nothing is known of William Rankin Allen including how this name was given to the sitter in the portrait. On comparison with examples in the V&A, from 1797, and The Cleveland Museum of Art, dated 1802, this miniature appears very similar, and therefore, quite certainly a self-portrait. The graphite portrait posited as an image of the artist in the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, is, however, is quite different from these three and as such is not at all persuasive as a self-portrait. I was able to examine the miniatures under magnification and learn more about the techniques of painting on ivory and Smart’s distinct style.

I was able to visit the Holburne Museum, Bath and see their innovative display of miniatures and engaging label texts. They encourage visitors to engage with the stories and ideas behind the miniatures along with the techniques that the artists were using. This is something I have tried to emulate with my project.

Outcomes

We wanted to highlight the loan of the Smart miniature and bring it to the public’s attention through gallery display, a lecture and the publication of online material. This work provided a good opportunity to research Smart, but also consider the place of his portraits within the collection so that visitors to the museum and more widely via the website can engage with the collection (the portrait collection, especially) in new ways. Portrait miniatures, due to their size and the way they are usually displayed (in cases and drawers) are often seen apart from other forms of portraiture and in this project I have tried to link them to paintings, drawings and prints (some of which are not on permanent display) thematically in order to broaden understanding and promote learning.

Furthermore, we plan to include this project, or elements of it, in a University of Cambridge Museums initiative focussing on family and relationships which will be part of the annual Festival of Ideas next autumn. The miniature of John Smart is on display for the first time – having always been in private hands – and beside the V&A’s self-portrait, is the only portrait of the artist on public display.

I will give a lecture in the Museum on Wednesday 31 July which is advertised online, in the printed What’s On booklet and will be highlighted in social media closer to the time. To coincide with the lecture I will make my work available to download as an online publication on the Museum’s website. This will serve as a permanent resource on the website.

Professional development

The Bursary has afforded me the time to research a new aspect of the Fitzwilliam’s collection. It has given me the chance to work on my own research while in the museum but, most importantly, gave me the opportunity to contact other institutions, archives, and scholars. My primary role at the Fitzwilliam is to facilitate other people’s research (I run the Graham Robertson Study Room, a job which does not take me outside of the Museum. With the Bursary I had the opportunity to visit other collections and archives as well as discuss my project with curators. The experience of visiting these places, enquiring at multiple other as well as dealing with the complexities required in executing the outcomes of the project was wholly beneficial to my professional development and is something I would not have been able to do without the Bursary. This work immediately helped me apply my skills to the next project I undertook: curating an exhibition at the Fitzwilliam, Fashioning Switzerland: portraits and landscapes by Markus Dinkel and his contemporaries, which opened on 4 June and runs until 15 September 2013. I had a large number of uncatalogued prints to work with and was granted funding to carry out research in Switzerland. My research was focused on Dinkel, a Swiss artist contemporary to John Smart, who painter small-format portraits in watercolour.