Sarah Backhouse, Exhibition coordinator, Royal College of Physicians, London

Initial scope

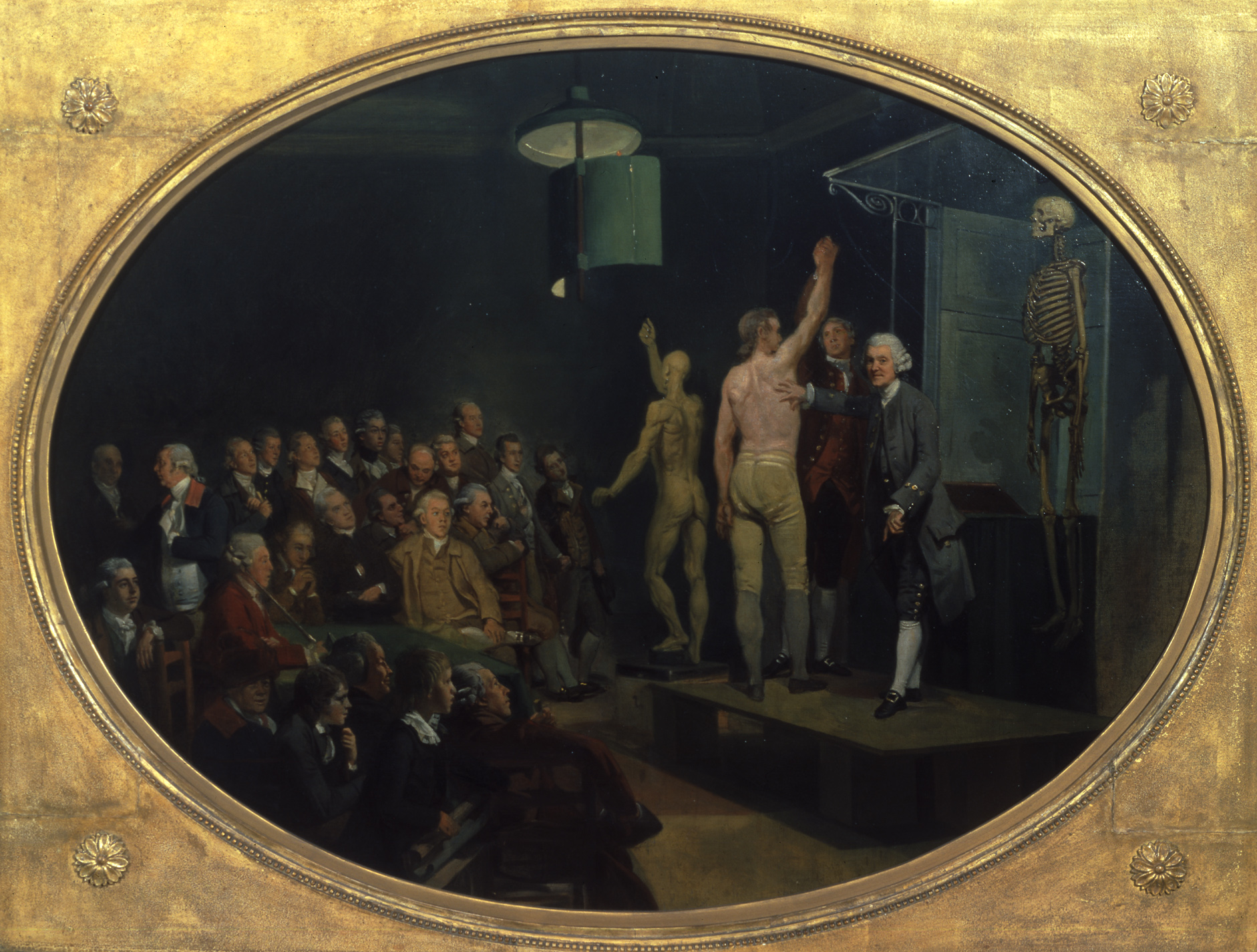

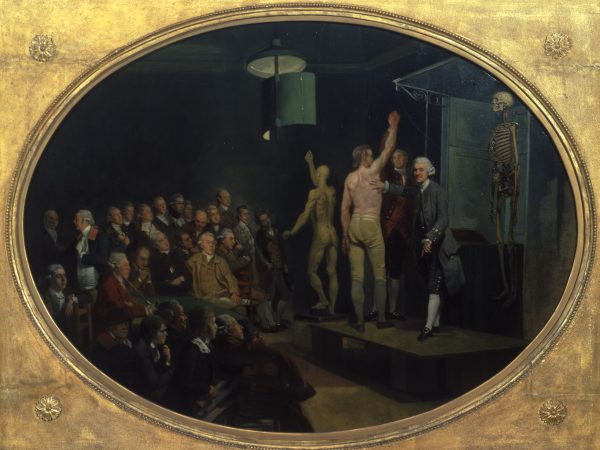

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) owns a painting by Johan Zoffany, ‘William Hunter lecturing at the Royal Academy’, painted c.1770-2. It is one of the most significant paintings in our collection, but we don’t fully understand what, or rather who, it represents. William Hunter – who became a licentiate of the RCP in 1756 – is lecturing to a group of 25 sitters, of whom only one has been positively identified. This is Sir Joshua Reynolds, president of the Royal Academy (RA), whose presence suggests that Hunter is lecturing to a group of RA members, in his role as the academy’s first professor of anatomy.

Hunter was a really interesting character. He was connected to all the important late-18th century societies, and was a well-known teacher and collector who built his own anatomy school and museum in London. This project, with its aims of identifying more of the sitters in Hunter’s audience, will help us understand more about the extent of Hunter’s influence, the social context within which the painting was commissioned, and how the RCP and its members can be situated alongside other historical institutions.

Principal findings

After reading through our portrait files and visiting the Heinz Archive and Library, I met with Martin Postle, Deputy Director of Studies at the Paul Mellon Centre, who has worked with the RCP on the Zoffany painting. He very kindly advised me on how to approach the research, and suggested that the sitters in Hunter’s audience might be members of other scientific societies who had a general interest in anatomy. He recommended that I look further into Hunter’s teaching of anatomy, at both the RA and his Great Windmill Street school. By identifying who attended Hunter’s anatomy lectures, as well as the circles that Hunter moved in, we might learn more about his teaching at the RA. Martin also recommended that I contact Helen McCormack at the Glasgow School of Art, whose PhD thesis on Hunter I had read in my preliminary research.

In March I visited Glasgow, to consult Hunter’s anatomy lecture notes in the university library’s Special Collections department, and to meet with Helen and staff at the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery. The conversations I had, and the research I was able to carry out there, resulted in some interesting finds and theories concerning the RCP’s Zoffany painting.

I was able to make some progress with identifying some individual sitters. Helen McCormack very kindly shared her speculative idea that the figure in the light suit in the centre of Hunter’s audience could be the English writer Edward Gibbon. He closely resembles Gibbon in other portraits, and we know that Gibbon attended Hunter’s anatomy lectures, although at a later date. Other sitters likely include George Michael Moser, who was the RA’s first Keeper of Schools, and is probably the figure in the foreground of the painting, looking out at the viewer and wearing a floppy hat (thanks to Martin Postle for this suggestion), Benjamin West (the figure seated two men to the right of Reynolds), Joseph Nollekens (the figure to the viewer’s right of West, with his chin resting on his hand), and Zoffany himself (the figure standing just behind and leaning forward towards Nollekens).

Dr William Hunter lecturing by Johan Zoffany, c.1770-1772 (detail). Royal College of Physicians, London

Beyond a few specific people, however, we may never be able to identify every figure in the audience – the painting is unfinished, and many facial features remain unclear. Martin Postle suggested we can however establish ‘types’ of sitter, and I have identified two. The first is the RA’s students, who are represented by the two boys in the foreground. Hunter’s RA lectures were addressed to the school’s students, which in the early 1770s included John Flaxman, John Hamilton Mortimer, William Hamilton, and James Northcote.

The other ‘type’ is society members and gentlemen of learning. Hunter himself acknowledged that not all members of his audience were students, so perhaps these other attendees were the same learned gentlemen who attended Hunter’s lectures at Great Windmill Street – Horace Walpole wrote that Hunter’s audience there included Edmund Burke, Adam Smith, Tobias Smollett, and Edward Gibbon. Hunter was very well connected through the Royal Society and the Society of Antiquaries to members with a known interest in the natural sciences, who may have also attended his lectures.

While looking through a notebook belonging to a student of Hunter’s, I found a previously unpublished sketch of what looks like a man performing a dissection. I believe this man represents Hunter, as it was drawn by a student attending his lecture – if so, this was a very exciting discovery, as we now have a new ‘portrait’ of Hunter to add to his known iconography!

Outcomes

This research enables us to better position the RCP, one of its most eminent members, and its most important portrait, within the wider context of 18th-century London society.

The research will be used to improve our interpretation of the painting, which currently hangs alongside the RCP’s set of 17th-century anatomical tables. The RCP’s museum staff give regular tours of the building and collections to visitors, and we are now able to include the Zoffany painting in these tours, and offer a clearer discussion about how the teaching of anatomy has developed over the centuries. This is a huge bonus, as these are key items in the RCP’s collection.

The research will be used to inform new interpretation of the painting for a 2018 redisplay, alongside the RCP’s copy of Hunter’s best-known work, Anatomy of the human gravid uterus (1774). 2018 is the RCP’s 500th anniversary, and special exhibitions are planned for this year, of which Hunter will play a prominent part – 2018 is also Hunter’s tercentenary.

The research also gives us the opportunity to update our database and portrait files to reflect current understanding of the painting, which is important because of its high profile.

Impact on professional development

This project has proved to be invaluable to my professional development. As well as having the opportunity to put by PhD research skills to direct use within my job, I have established professional contacts that have been both useful and enjoyable.

The RCP has a significant portrait collection. As an Art History graduate I have a strong interest in working with portraits and portrait collections, but have not studied 18th-century portraiture for many years. Working on this project has widened my knowledge and skills within a type of collection that I hope to work with more in the future.