Amina Wright, ‘Joseph Wright of Derby. Bath and Beyond’ reviewed by Alice Insley, University of Nottingham

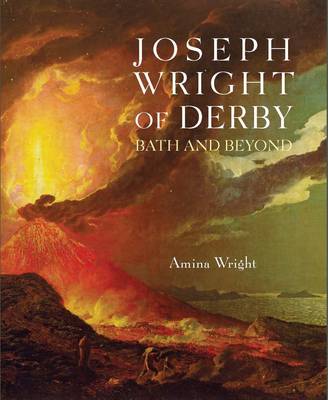

Amina Wright, 'Joseph Wright of Derby. Bath and beyond', Philip Wilson Publishers, January 2014

This catalogue, produced to accompany the exhibition of the same title recently at the Holborne and soon to open at Derby Museum and Art Gallery, examines a period in Joseph Wright’s life which has been largely overlooked in scholarship on the artist. As Amina Wright, author of Bath and Beyond but of no relation to the artist points out, the time that he spent in Bath from November 1775 until June 1777 is generally believed to have been highly unsuccessful, with Benedict Nicolson labelling it the ‘dismal Bath episode’ in his 1968 biography. Having discovered picture labels on the back of three portraits of the Darwin family where the epithet “Wright of Bath” is used instead of the usual “Wright of Derby”, this catalogue has sought to reexamine Wright’s short stay in Bath, claiming that far from being a ‘disaster’ it was an important period in Wright’s career, a time which enabled him to build a reputation as an exhibitor, experiment with new subjects, and assess and consolidate all he had learnt during his tour of Italy.

Following the premise of this argument, and in correlation with the hang of the Holborne exhibition, the narrative of the catalogue traces Wright’s career in Bath through thematic chapters which discuss the decision to move to Bath, his attempts to establish himself as a portraitist, the development of his exhibition pieces and turn to new genres, and, ultimately, his return to Derby in the final chapter entitled ‘Retirement’. This not only lends itself to a considered analysis of Wright’s two years in Bath, but also allows the narrative to be underpinned by Amina Wright’s central argument for the importance of Bath within his career because of the nature of the town itself, which she proposes was not just a fashionable resort diametrically opposed to industrious Derby, and the paintings he produced during this period.

This narrative is clearly structured and comprehensive, and one of the strengths of the book, and what makes it so rich, is Amina Wright’s ability to draw out particular histories through her in-depth interpretations of the works within the exhibition. For example, Chapter 2, which focusses upon Wright’s attempts to establish himself as a portraitist in Bath, is discussed largely in relation to his portrait The Rev. Dr. Thomas Wilson and his adopted Daughter Miss Catherine Sophia Macaulay (1776). Through the painting, which was intended to announce Wright’s arrival in Bath and his skill as a portraitist, Amina provides a rich visual analysis of the work and also draws together information about the sitters; the portrait practices in Bath, particularly Wright’s need of a patron; competition between artists (or lack of it), and the social networks and connections within the town as well as the opportunities these offered.

The Reverend Thomas Wilson (1703–84) and Miss Catherine Macaulay (1731–91) by Joseph Wright of Derby © Chawton House Library

As the paintings Wright produced during his two years in Bath are the basis on which the artist’s residence in the town is deemed a success, it seems fitting that two of the chapters are dedicated to the experiments he was making in new subjects. Chapter 3 ‘The most wonderful sight’ looks at the Italian subjects that Wright exhibited in his rooms in Bath, and Chapter 4 ‘Artist and bard’ focuses upon his sentimental and literary paintings; both these chapters are notable for the fresh perspective they offer on Bath as a productive and formative time for Wright’s oeuvre as well as their beautiful and well laid out illustrations. By moving away from the more traditional measure of Wright’s success in Bath as based upon his portrait practice alone, the catalogue is able to suggest that it was in the time made free through lack of commissions that he began to experiment with new subjects, develop his exhibition pieces, and consolidate what he had learned in Italy. Chapter 4, which focuses upon his experimentation with literary and sentimental subjects pushes the significance of this even further by noting that the melancholy sensibility developed in his paintings ‘expressed his own image as an artist’, implying that it was in Bath that Wright developed his later public identity. Whilst this poses the question as to whether he would have made these experiments wherever he was living, these chapters still represent an interesting approach to some of his most iconic paintings.

As is inevitable with the subject under examination, references to Bath itself are woven throughout the narrative of the catalogue, but the town is only really discussed directly in Chapter 1 ‘Unknowing or unknown’, where the reasons for Wright’s move to the town is set out and more detail is given about the attractions and history of the place itself. This is both a strength and weakness within the book, as it avoids Bath becoming “over-done” in the narrative, but does often leave one hoping for a more in-depth look at Bath which would reflect the complexity of the art world and society during this time, particularly as the town itself was changing physically and socially. There are some sharp and insightful comparisons made between Bath and other places Wright spent time in during his career, such as the comparison drawn between his success as a portraitist in Liverpool and his failure in Bath due to a lack of patronage and difference in the market, and the positioning of Bath as a continuation and consolidation of the fruits of Wright’s labour’s in Italy. However, despite this, there are moments where Bath seems to have been simplified into being an artistic platform which Wright failed to be able to take advantage of due to a lack of connections.

The final chapter, ‘Retirement’, addresses the relationship between Wright and Bath more directly, raising the issue of Wright’s disappointment in the town and final departure back to Derby. Bath is positioned as a productive and industrious environment, able to nurture creativity and innovation, while Wright, unable to make the most of this in the way he had hoped, returns to his hometown. Through focusing upon Bath in this way, the catalogue raises questions regarding the tensions in associating a painter with a particular place. In the past the conception of Bath as fashionable and frivolous has meant it has been disconnected from Wright who was understood as scientific and serious, and this, on the flip-side, has meant his hometown has been privileged above all other places as the ‘right’ place for the painter. By challenging this viewpoint the catalogue highlights the need to explore the changing relationship between painters and places and how these have been understood or interpreted at different points in time. Therefore, whilst Wright’s relationship with Bath does need to be viewed within the wider perspective of his career, something which is briefly addressed in the introduction, it demonstrates that the relationship between painter and place shifts in Wright’s case. Through reappraising Wright’s time in Bath, the catalogue therefore opens up bigger questions about the nature of Wright’s identification with his hometown and how this has since been interpreted, particularly when, as this catalogue highlights, he did have productive times elsewhere.

However, above all, the catalogue succeeds in throwing new light on a period in Wright’s life which has hitherto been neglected and disregarded. It is extremely well researched and provides new insights into Wright’s time in the town, such as the possible identification of ‘4 heads’ Wright painted during the Bath period, including the beautiful portrait of Agnes Witts (1776). As both exhibition and catalogue, Bath and Beyond provokes further questions, draws ones attention to both familiar and lesser known paintings, and leads to further consideration of the richness and complexity of Wright’s achievements.

Alice Insley is a doctoral candidate at the University of Nottingham >>