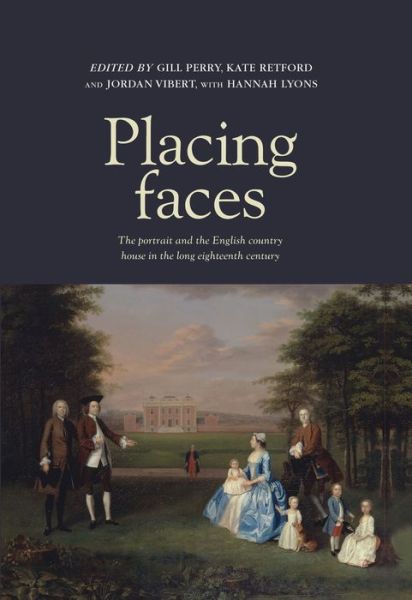

Gill Perry et al (eds), ‘Placing Faces: the portrait and the English country house in the long eighteenth century’ by Stephen Ponder, Curator, National Trust South West Region

'Placing Faces. The portrait and the English country house in the long eighteenth century', edited by Gill Perry, Kate Retford and Jordan Vibert, with Hannah Lyons. Manchester University Press, Nov 2013

As a National Trust curator for country houses with 18th century portraits in their collections, I hoped this book would increase my understanding of how portraits were commissioned and displayed and their meanings understood. It did. But despite the title, this is not a definitive overview of the subject. It is a series of essays on different aspects, offering a partial view of the subject rather than a strong narrative. The essays will inevitably be of varying interest to different readers.

Introduction: placing faces in the country house by the editors efficiently sets out the context of the subject and of recent research including cross-disciplinary exploration of definitions of the ‘home’ and its complexity with reference to 18th century country houses, but offers no particularly striking fresh insights. It opens vividly with Samuel Curwen’s visit to Stourhead on 24 September 1776 and his description of Dahl and Wootton’s vast portrait of Henry Hoare on horseback ‘in this hall hangs a full length picture of Mr. Hoare on horseback drawn in younger days, the face, the drapery and the Horse executed by different hands, as the Housekeeper told’. The assertion that Henry Hoare’s portrait has to be seen ‘In the Hall’ at Stourhead, that ‘face and place are indelibly linked’ and ‘The messages conveyed by a portrait…are clearly affected by (and affect) the location in which it is displayed.’ is clear enough, but surprisingly omits to mention that the Hall today is an Edwardian re-creation and colour scheme after fire gutted Stourhead’s central block in 1902.

The book is arranged in 3 overlapping sections. A walk around the house concentrates on particular rooms in particular houses – the saloon and ballroom at Wanstead, the library at Narford and the Sculpture Gallery at Chatsworth – and how portraits interacted with them. I found this the most interesting part of the book. Kate Retford’s The topography of the conversation piece: a walk around Wanstead is an insightful piece which draws on a variety of disciplines including architectural and garden history to explore The Tylney Family in the Saloon at Wanstead by Nollekens and Hogarth’s Assembly at Wanstead House. The portraits, architectural plans and exterior views and written descriptions are skilfully used to conduct us on a virtual tour of the lost great house and show how understanding the setting hugely increases understanding of the significance and meanings of the pictures. I found this a compelling reading. It hangs on the recent identification of the Nollekens as showing Wanstead, fully confirming the opening statement that ‘Biography is paramount in connecting the portrait and the house which can draw out its full meaning and significance.’

Life in the Library by Susie West is a welcome introduction to Sir Andrew Fountaine and his library at Narford Hall, examining its sequence of portraits of great men and how they contribute to the interior scheme. It illustrates a key theme that while family portraits are the heart of collections they are by no means the only faces – mistresses, friends, kings and queens, historical figures, and contemporary worthies. It gives a succinct account of how the library’s place in the house plan changed during the 18th century from an essentially private room to a more public space. Given the importance of the discussion about the relationship of the library to other rooms it is disappointing that Narford’s plan is not illustrated. The diagram illustrating the cultural relationships between the sitters is revealing and repays study as a method of analysis. I would have liked more explanation of some points e.g. much is made of the significance of the Mazarin cabinet, but although discrepancies between the Mazarin inventory description and the cabinet at Narford are highlighted they are not explained.

Women’s space? focuses on the complex relationships between aspects of femininity and public/private spaces. For me Ruth Kenny’s ‘Apartments that are not too large’: pastel portraits and the spaces of femininity was something of a revelation, notably in its analysis of parallels between pastel’s physical qualities and what they were used to represent, such as the observation that they reflect women’s daily toilette, its dry surface mimicking the use of powder. The links between pastel as a feminine accomplishment, women as the principal purchasers of pastel portraits and the rooms in which they were displayed are very well drawn out.

Georgiana at Althorp: Spencer family portraits 1755-83 by Emma Barker assumes that the reader will already be familiar with her story. The essay aims to explore the process by which the group of portraits came into being, the functions they were intended to perform and the spaces in which they were displayed, but I did not feel it fully achieved those aims. There is very little detail about the spaces in which they were displayed in the period under discussion. The various portraits of Georgiana and her siblings ‘most probably hung in their mother’s bedroom or dressing room’. We are told that Lady Spencer hung the Reynolds portrait of her daughter the Duchess in her bedroom at Althorp but given no information about the room or how the painting was hung in it.

Imperial designs looks at great contemporary heroes. Harriet Guest’s Commemorating Captain Cook in the country estate makes fascinating reading, but the connection with the book’s subject feels rather tenuous. The element of portraiture involved in the discussion of Stowe and The Vache is limited to ‘a pedestal bearing an unrecognisable portrait profile’ at Stowe. The representations of the death of Cook which are discussed are surely more in the nature of history painting than of portraiture. The essay feels better suited to a study of the country estate owners who commemorated national heroes and events in their grounds. Desmond Shawe-Taylor’s The Waterloo Chamber before the Battle of Waterloo provides compelling analyses of portraits by Reynolds and Lawrence.

The essays are generally well-written and readable, not overburdened with academic-speak. The book is well designed and attractively laid out with good quality paper and printing. Illustrations are a little disappointing: only 19 are in colour, and many are half page in a small format book so are not easy to see clearly. The Narford library is a half-page black and white photograph in which it is almost impossible to make out many of the portraits, and none of them are illustrated individually. One or two look rather makeshift e.g. figure 1. The Hall at Stourhead appears to be a snapshot on an open day. Overall this is a useful contribution to the subject, though perhaps not a book I will return to again and again.