Lace for Lady Anne Clifford by Gilian Dye

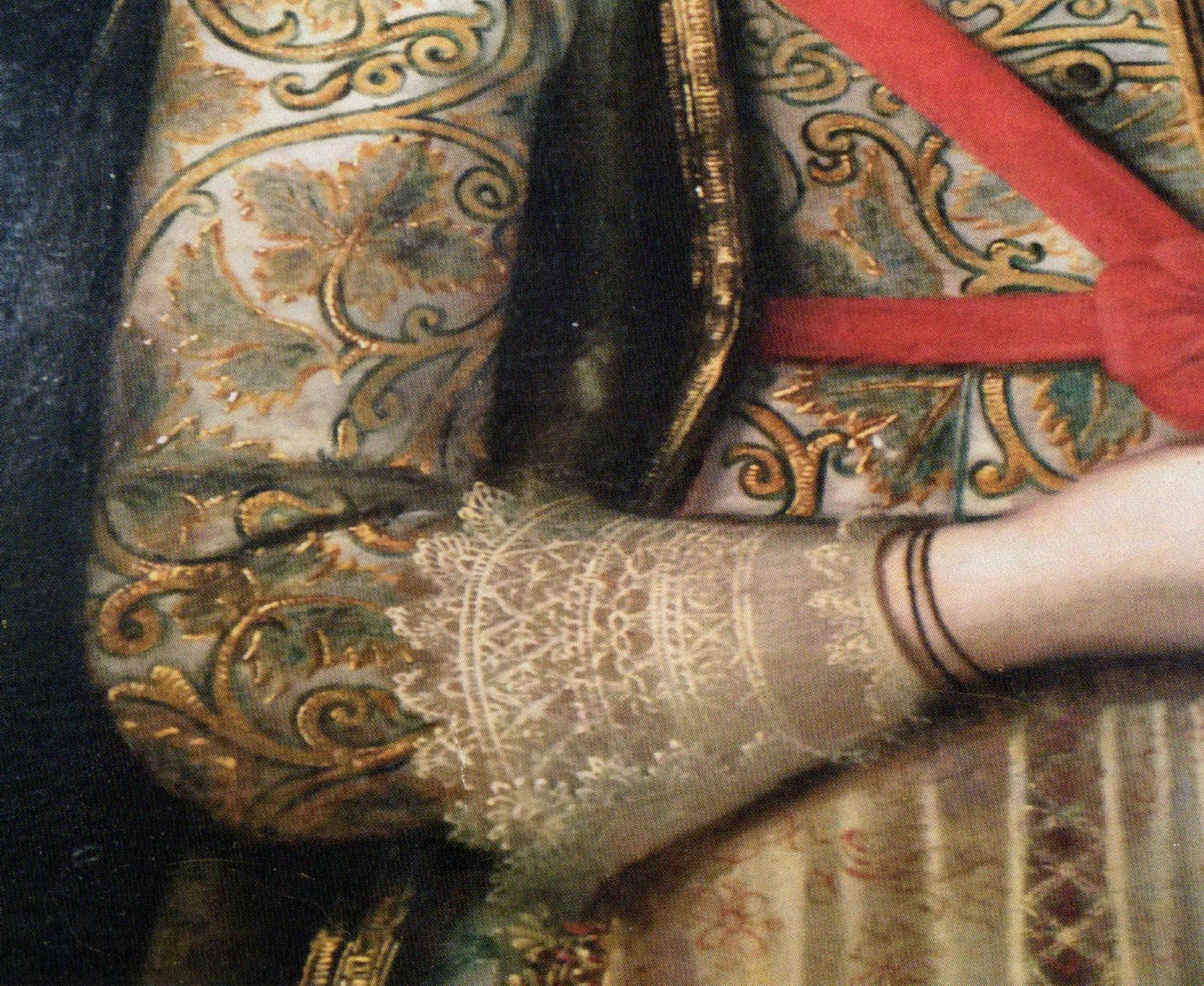

Fig 1. Portrait of Lady Anne Clifford by an unknown artist, courtesy of a private collection

Sixteenth and seventeenth century portraits are a wonderful resource for lace historians. Two types of lace evolved during the sixteenth century: needle lace and bobbin lace. Needle lace, as the name suggests, is a form of free embroidery, worked with a needle and a single thread, while bobbin lace is a combination of plaiting and weaving worked with multiple threads each wound on a small handle known as a bobbin. The two techniques are totally different, however the results can look remarkably similar and by 1600 bobbin and needle lace seem to have been equally valued and often used together. Portrait artists clearly recognized the importance of lace to their clients and many developed the skills to paint ruffs, cuffs and other high fashion items in such detail that it is possible for a modern lacemaker to distinguish between the two types of lace and produce accurate copies.

Most lacemakers are content with a small sample, or perhaps a cuff or ruff, however a few groups have tackled reconstructions of entire outfits. One of these groups, based in Appleby in the Lake District, was given permission to study an early seventeenth century portrait of the feisty Lady Anne Clifford1 and attempt a reconstruction of the clothes she is wearing. The portrait (Fig 1) is in the private collection of Lady Anne’s family, who still live in the Appleby area which was Anne’s home.

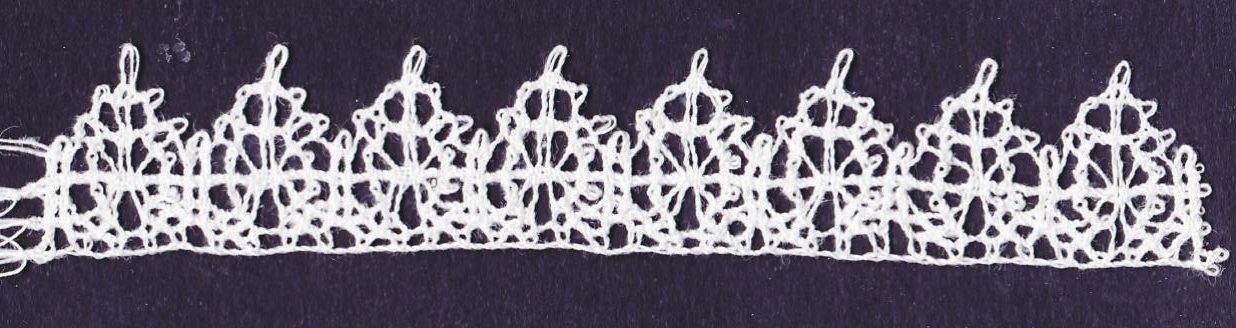

In 2015 I was approached by one of the group, Marjorie Hanson, for help with the lace. Marjorie, an expert lacemaker, had at that time no experience of working seventeenth century lace, but knew that it had been the focus of my research for many years. From an amateur photo of the cuff (Fig 2) I could see that the lace was bobbin lace and I was able to draft a pattern for the scalloped edge and work out the techniques that Marjorie would need. Bobbin lace was in its infancy in the seventeenth century and the working had more freedom than it often has today, so it would be a steep learning curve, starting with a sampler of the basics. Several email exchanges later Marjorie had mastered the early techniques and embarked on her first scalloped edging. (Fig 3)

Fig 2. Detail of Lady Anne’s cuff in Fig. 1. Photograph courtesy of a private collection.

Fig 3. First attempt at scallop edging for the cuff.

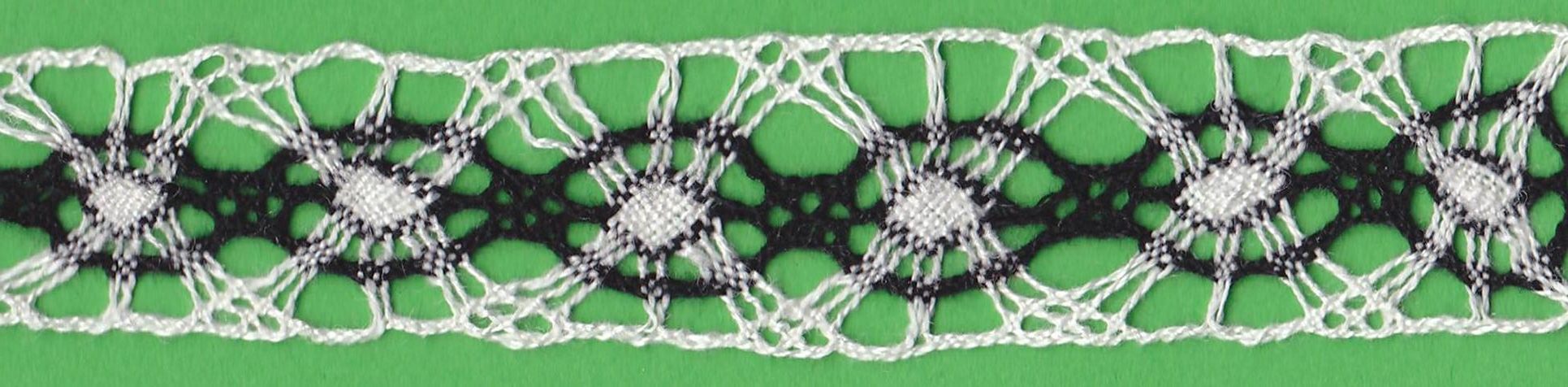

The next project was the long apron with its red and white insertions and scalloped edging. It was fascinating to discover that the pattern of the insertion exactly matches a black and white insertion (Fig 4) in a waistcoat now in the V&A (ref T4-1935), but originally from the Isham family. I had previously worked out a pattern for this2 and after a few false starts Marjorie had little problem in working one length before handing over the second to her colleague Barbara Smith and requesting a pattern for the edging. It is possible that a different hand had painted this lace as the stitches are not as clearly depicted and a certain amount of guesswork was needed to produce a workable pattern. By this time Marjorie was well practiced in early lace and was able to tackle this more complex scalloped edging with considerable confidence, completing all 130 inches in just 75 hours.

Fig 4. Two-colour insertion by the author

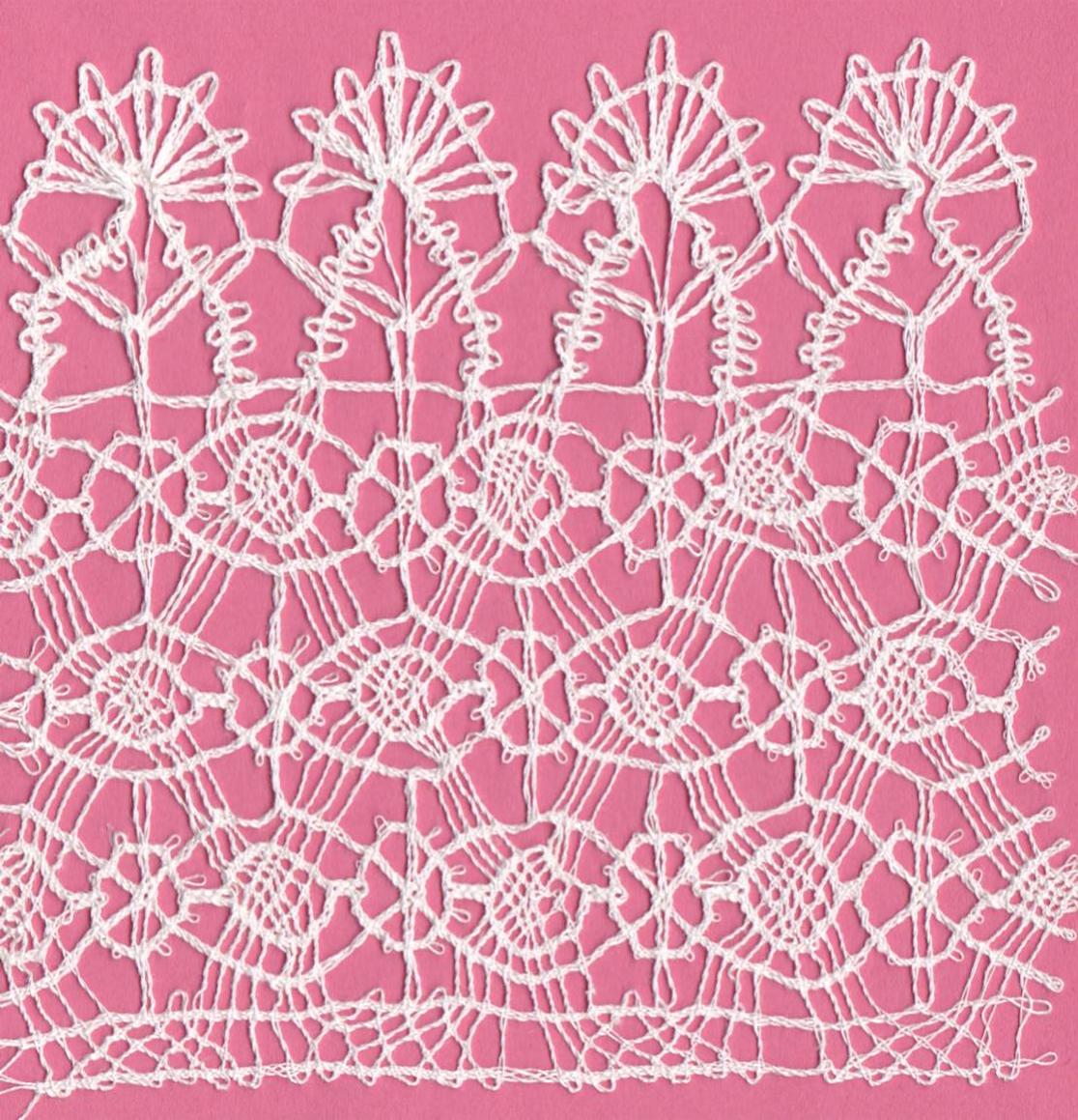

Then the group decided the cuff needed more lace than a scalloped border so we looked at the possibilities. The original would probably have been worked all as one piece - as in this sample from Schole-House for the Needle3 (Fig 5) - but there seemed no reason not to work it as separate strips. We chose one strip that matches both the collar worn by the Little Girl with a Basket of Cherries (National Gallery, London, ref. 6161), and a lace in the Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth collection at Gawthorpe Hall. Also in the RKS collection is a ‘fir-tree’ lace that provided the pattern for another insertion.

Fig 5. Interpretation of a pattern from ‘Schole-House for the Needle’, 1632

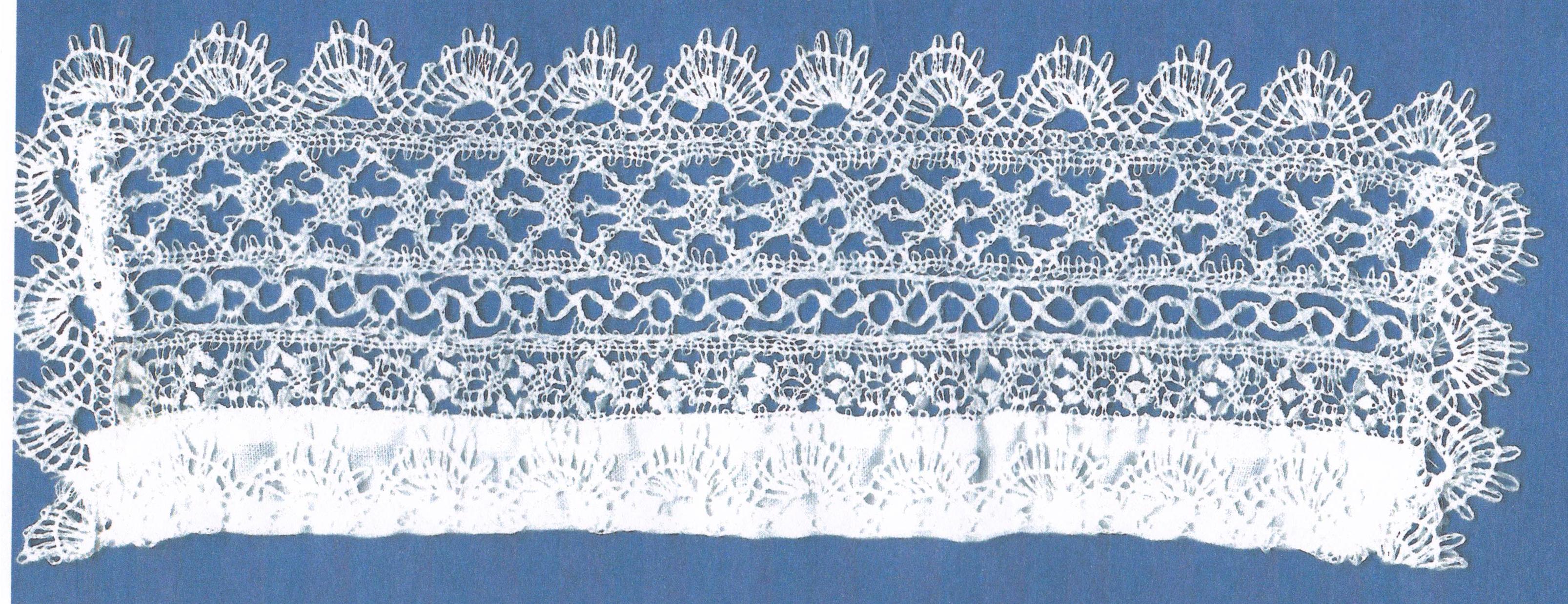

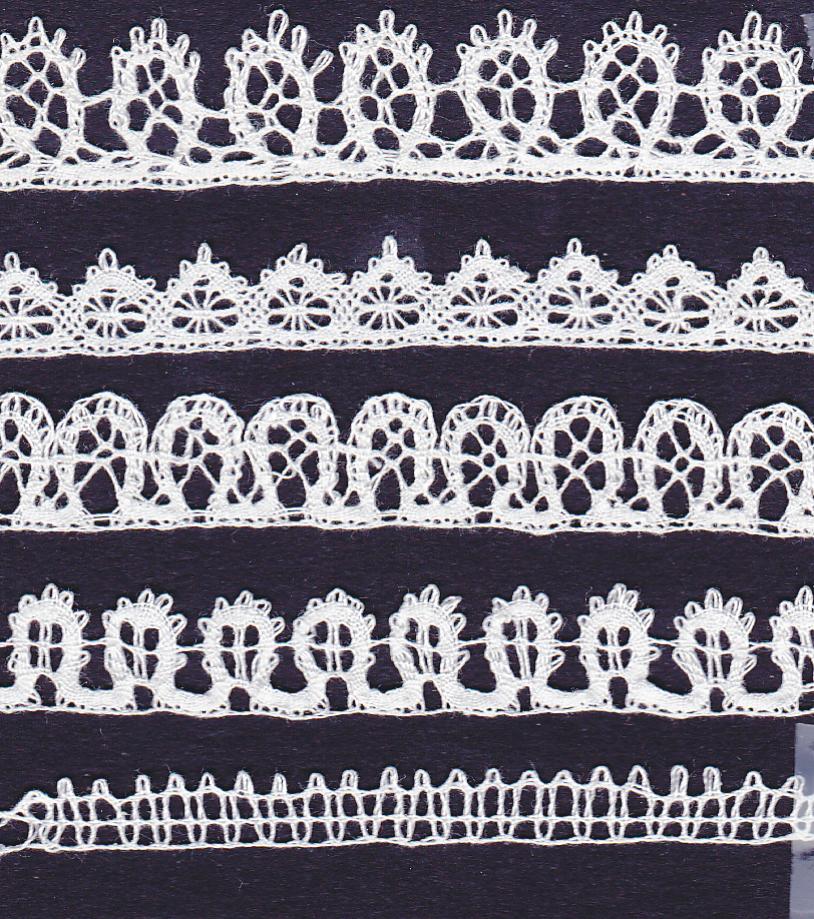

Cuff completed (Fig 6) and Marjorie and Barbara are now working on Lady Anne’s ruff, starting with 2½ yards of a narrow lace as an edging for one layer; this has taken around 60 hours of work. The pattern for this is an adaptation of the lace on a child’s shirt4 in the Birmingham Museum (Fig 7). This lace is one of the family of narrow edgings that are related to five tiny samples attached to a letter written by Elizabeth Isham in the 1620s. Elizabeth was telling her father that these were the type of laces he should be buying for his ‘bands’ (ie collars) and she gives the prices - from the top: ten pence; seven pence; two at six pence and the smallest two pence (Fig 8). The Birmingham lace would come towards the top of that scale - say 10 pence - and if these are prices per yard, which seems most likely, then that length of Marjorie’s edging would have cost 25 pence (just over 2 shillings) at a time when the steward of a large household was earning about £10 (200 shillings) a year. From my own experience I know that 2½ yards will only make a small ruff, larger ruffs might require ten times that, i.e. equivalent to a steward’s annual income.

Fig 6. Cuff for Lady Anne worked by Marjorie Hanson and Barbara Smith

Fig 7. Sample of lace for shirt

Fig 8. Reproduction of the samples on Elizabeth Isham’s letter

This ongoing collaboration continues to raise as many questions as it answers. Who in the seventeenth century was making the lace? We know from various records that bobbin lace was being made in London, Devon, Suffolk and the East Midlands and there is a good chance that all the bobbin lace in this full length portrait was made in either London or Northamptonshire - home to the Isham family and to Lady Anne’s relatives. But where did Lady Anne get the needlelace that she is wearing in the William Larkin portrait at the National Portrait Gallery (Fig 9)? There are no specific records of needle lace being made commercially in England. We know from Anne’s diaries that this portrait was painted at Knole in the summer of 1618 when she was married to Richard Sackville and would have had access to lace imported from Italy and the Low Countries. Other portraits of the family by Larkin show them wearing both bobbin and needle lace so why did Anne chose to wear only bobbin lace - and a lot of it - for the Appleby portrait? Was she trying to support the home industry? What, if any, are the connections between Lady Anne and the Isham family? Are there more portraits that can be linked to surviving lace? For example Sir Walter Pye’s ruff (Fig 10), painted by Cornelius Johnson, is edged with the ten pence lace from the Isham samples; can we ever directly link lace on a portrait with the makers…?

Fig 9. Anne, Countess of Pembroke (Lady Anne Clifford) by William Larkin, oil on panel, c.1618 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Fig 10. Walter Pye (1571 - 1635) by Cornelius Janssens van Ceulen, also called Cornelis Johnson or Cornelius Jonson (London 1593 - Utrecht 1661), Wallington, Northumberland www.nationaltrust.org.uk © National Trust Images

One thing that is certain is that a hands-on approach to understanding the lace on sixteenth and seventeenth century portraits leads to an enormous respect for the artists - and lacemakers - of the time. The portraits may be considered by some critics as wooden or formulaic, but it is clear that they were an accurate representation of the finery being worn - so exactly what was required by their clients.

- More information about Lady Anne and her life can be found in: Proud Northern Lady by Martin Holmes, first published in 1975 with reprint in 2012 by The History Press, ISBN 978-1-86077-179-8;The Diaries of Lady Anne Clifford, edited by DJH Clifford, first published in 1990, reprinted in 2015 by The History Press. ISBN 978 0 7509 3178 6.

- Pattern published in Insertions and Borders by Gilian Dye, Cleveden Press.

- Schole-House for the Needle was the first book of lace patterns to be published in England, in 1632.

- Patterns for these narrow edgings are in The Isham Samples and other Linen Edgings by Gilian Dye.

Comments

My stumbling fingers could neverdo this beautiful bobbin lace, but thank

goodness my mind can enjoy the beauty - and the art the reproducers

have accomplished. Loved this !

So pleased you enjoyed the Lady Anne Clifford blog, it has been a fascinating ongoing study and this week I am using Lady Anne’s lace as an introduction to the working of 17th century bobbin lace to a new group of lacemakers

Gil