Portraits of Domesticity and Collecting in the V&A’s Europe 1600-1815 Galleries, by Dawn Hoskin

The Dutch Domesticity display in Gallery 7 of the Europe 1600-1815 Galleries, 2016. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

I attended the Decoding the domestic interior in British portraits seminar at the Geffrye Museum, ostensibly in my current role as Assistant Curator of Furniture, Textiles and Fashion at the Victoria & Albert Museum – these of course all being types of objects commonly found within portraits. Not being a portrait specialist nor someone focused solely on British material, I was interested in further exploring issues surrounding the use of portraits as research tools for understanding objects within our collections. The day offered many reminders, warnings and advice of how to approach representations of interiors and what information it may (or may not) be possible to extrapolate from them.

Dr Tara Hamling emphasised the importance of being aware (and wary) of how to read ‘evidence’. Inverting the question of ‘What can portraits tell us about interiors?’ to ‘What can interiors tell us about portraits?’ helped to reinforce the need to consider all possible motivations behind all elements of a portrait. As Angela Cox noted, key initial questions should include: what kind of reality does the painting/portrait show? And what are its overlapping functions? Later in the day key questions raised included: who commissions or prompts production and what is their purpose or expectation?

In addition to prompting strategies for future research, the day led me to reflect on research undertaken in my previous role working on the V&A’s Europe 1600-1815 Galleries. Recognition that interiors can display not just wealth but also identity and values (e.g. piety), in addition to conforming to fashion and conveying social status, was something I had been particularly aware of whilst researching for our Dutch Domesticity display in the Europe Galleries.

The Dutch Domesticity display in Gallery 7 of the Europe 1600-1815 Galleries, 2016. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The display considers the period following the 1648 recognition of the Dutch Republic as an independent state, free from the political and religious domination of Catholic Spain. The new Protestant republic was the most powerful trading nation in Europe, and the economy prospered. Many people had more money to spend on domestic comforts, fewer married women had to work and the focus of most women’s lives was their families and homes, where the day-to-day management of the household was seen as a Christian duty. This can be found reflected in the interiors of the time.

‘Full of pleasure and home contentment, with rich cupboards, cabinets etc., imagery, porcelain, costly fine cages with birds etc., all these commonly in any house of indifferent quality; wonderfully neat and clean.’

Peter Mundy, Travels in Europe, 1640

Left: Linen cupboard (kast), oak inlaid with ebony; ebonised feet, Dutch Republic (now the Netherlands), 1620–40. Museum no. 860-1907 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Right: A Family Group in an Interior, attributed to Quiringh van Breckelenkam, ca.1658-70 J. Paul Getty Museum

The quantity and quality of a family’s household linen was a mark of status throughout Europe. Notably, in the Dutch Republic, highly decorated pieces of furniture for pressing and storing linen were proudly displayed. They feature in many paintings from this period. This lockable linen cupboard (above left) would have dominated the ground-floor front room of a Dutch townhouse. Made to hold a housewife’s precious stock of household linens, it also served to impress visitors. The combination of ebony details with oak is typically Dutch and was also seen in the panelling of rooms. Informed by both visual and written accounts, we decided to place two Chinese bowls and a bottle on top, to reflect that imported Chinese ceramics could be displayed on top of tall pieces of furniture like this (as seen above right).

(You can also read about our use of the painting above to help inform the display treatment of a 17th century cushion on the Europe Galleries blog here)

The Dutch Domesticity display also came to mind during Dr Kate Retford’s consideration of the use of generic settings in the 18th century, which warned us against applying contemporary ideas to the use of portraits in social positioning. In contrast to frequent assumptions of their purpose being to aid social-climbing (mimicking and aspiring to those above them in society), intentions of conforming and consolidating social status were proposed. It was interesting to later hear artist Andrew Tift’s personal objective ‘to reflect and reinforce the identity of the sitter’ in a portrait.

Depictions of collections can offer not only visual documentation but also a ‘portrait of connoisseurship’. Kate’s reference to Zoffany’s portrait of Sir Lawrence Dundas and his grandson, in which all the objects can be matched to 1768 inventory of ‘Sr Lawrence’s Drawing Room’, called to mind the inclusion of John Jones within the Europe Galleries.

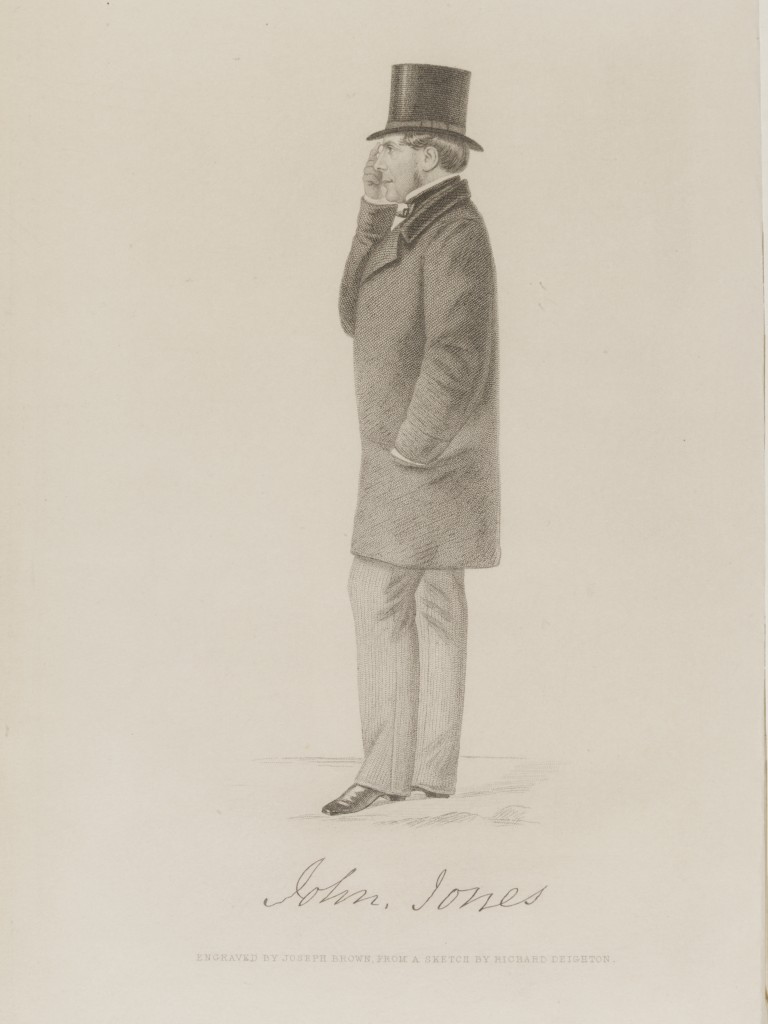

John Jones (1799-1882) made a large fortune manufacturing military uniforms before retiring to focus on collecting fine and decorative arts. In 1865 he moved to a townhouse at 95 Piccadilly, Mayfair. Here, he arranged his collection carefully, often grouping objects by maker, period, medium, style or historical association. The rooms became crowded with his collection of furniture, ceramics, metalwork and other objects.

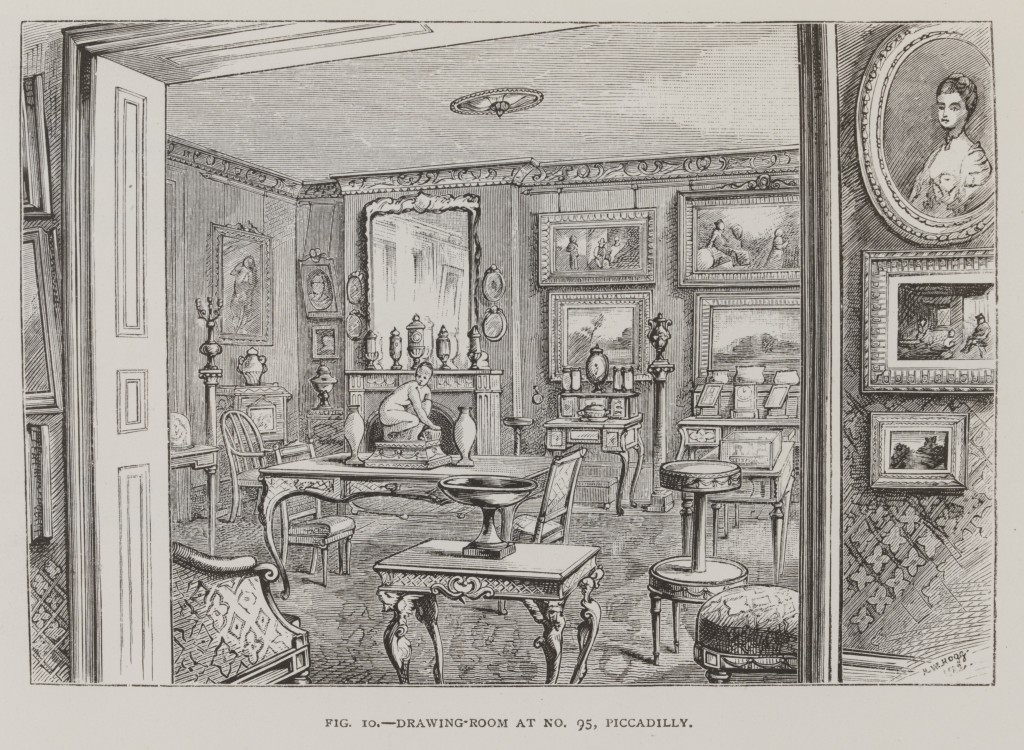

Drawing Room at No.95 Piccadilly, from the Handbook of the Jones Collection in the South Kensington Museum, letterpress and woodcuts, published for the Committee of Council on Education, England (London), 1883. National Art Library © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

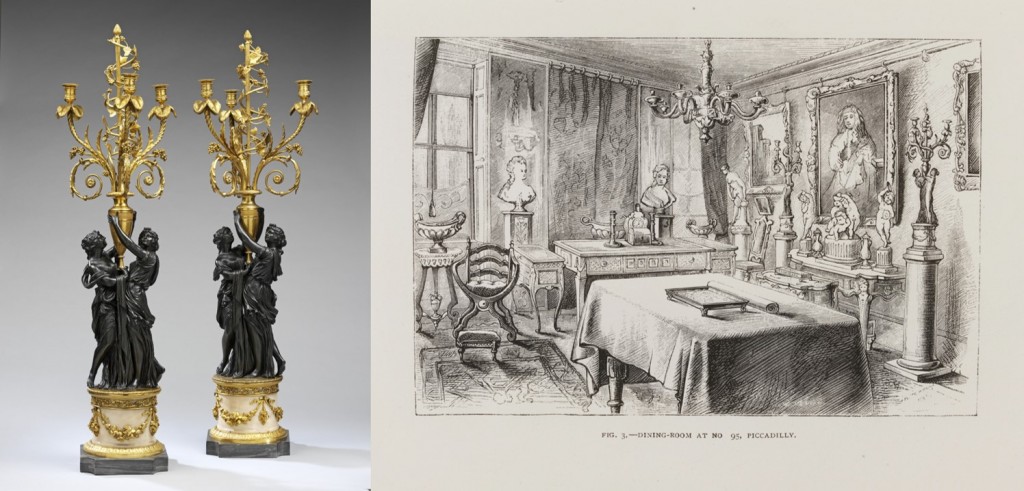

He left his collection to the V&A ‘for the benefit of the nation’. When his collections entered the Museum, the importance of recording Jones’s arrangement was immediately recognised. In 1883, the Museum published a handbook illustrating the contents of the house, which was considered crowded, even by Victorian standards. Within them we can identify objects from our collections, such as this pair of late 18th century French ormolu candelabra, each supported by two draped classical female bronze figures.

Left: Pair of ormolu three light candelabra, France, 1770-80. Museum number 964-1882. Right: The Dining Room at No.95 Piccadilly © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The engravings suggest how John Jones lived with his collection, the interiors being a combination of private and public display. When thinking about them during the seminar it took me a while to recall that, whilst I often consider the interiors to be a portrait of Jones and his collection, he is not in fact depicted within any of them – his portrait is instead included on a separate page.

John Jones, engraved by Joseph Brown, from a sketch by Richard Deighton © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In total, John Jones’ bequest comprised 1,034 objects (excluding the books).This generous gift now forms the foundation of the 18th century French decorative arts collections in the Europe galleries. Other objects from his collection can be found throughout the Museum. A new digital interactive now enables visitors to the Europe 1600-1815 Galleries to explore the engravings of the interiors and learn more about John Jones and his bequest.