New research on rare clay portrait figure by Chitqua

1. Thomas Todd by Chitqua, c.1770, clay statuette (detail) © Museum of London

Paper by Pat Hardy, Curator of Paintings, Prints and Drawings, Museum of London.

January 2013.

This rare and engaging figure of Thomas Todd (Fig. 1) a London merchant, is one of the few works to have survived intact which can be attributed to the Chinese artist Chitqua or Tan-Che-Qua (c.1730- c.1796). It was recently acquired by the Museum of London. Chitqua was the only Chinese artist to have been recorded as working in Britain and producing these unusual clay figures in the eighteenth century and there are no records of British born artists producing clay portraits in this manner.

Chitqua arrived in London in 1769 aboard the East Indiaman Horsendon from China, probably from Amoy in Canton, where he was well known for keeping a shop in which he made statuettes. Why he came to London is unclear but possibly he saw a new lucrative market, possibly he had a sponsor but at the moment no evidence suggests this. He remained in London working at a hatter’s shop in Norfolk Street until his return to China in 1772. He was described by antiquary Richard Gough as aged about forty when he came to London so his date of birth can therefore be estimated as c.1730.

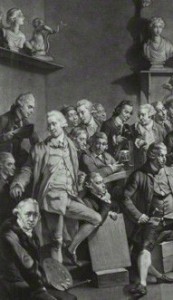

2. The Academicians of the Royal Academy by Richard Earlom, after Johan Joseph Zoffany, mezzotint, published 1773 © National Portrait Gallery, London. In this detail, Chitqua can be seen in the centre background.

Chitqua himself was painted or drawn at least three times and his most celebrated portrait was by Johann Zoffany which appears in The Academicians of the Royal Academy (1771-2) and reproduced as an engraving (Fig. 2). He is more clearly depicted in an oil painting attributed to John Mortimer Hamilton, exhibited at the Society of Artists 1771 (Fig. 3) as well as a chalk drawing in the Ashmolean by Charles Grignion the Younger.

While in London Chitqua worked as a modeller producing likenesses of sitters and was labelled a facemaker. Commentators believed he used clay he had brought from China and conservation records on the figure of Thomas Todd suggests that he certainly imported a distinctive mix of material as well as technique. He charged 10 guineas for a bust and fifteen for a whole-length with the latter averaging 40cm in height. The Todd figure is 33 cm high.

3. Portrait of Chitqua by John Hamilton Mortimer © Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons

Mixing in eminent circles in London society as shown by his presence at the Royal Academy, Chitqua was very positively received and appears to have been treated as a visiting foreign dignitary, for instance he obtained an audience with George III. He actually exhibited a clay figure at the Royal Academy in 1770, (unfortunately the sitter was not identified) and was recognised as producing striking likenesses of those he modelled. The Gentleman’s Magazine commented on this ‘ingenious’ Chinese artist ‘whose models after life have been so justly admired’. After two years in Britain Chitqua is recorded as liking his own climate and therefore attempted to return to China on the ‘Grenville’ in March 1771. In an incident-packed trip he fell overboard soon after departure, was picked up by the crew and was eventually put ashore at Deal. He spent another year in London before making the successful trip back to China in 1772. His history after leaving England is obscure but the Gentleman’s Magazine in May 1797 reported that news had been received in Madras in December 1796 that Chitqua had died after taking poison.

Very few of the clay figures he produced appear to have survived, not surprisingly in view of their fragile nature and only the following named figures have so far been ascertained as being by or attributed to Chitqua, namely the Todd figure, one of physician Anthony Askew in the collection of the Royal College of Physicians in London (Fig. 4) a figure identified as David Garrick in a private collection (Garrick and Chitqua met at a Royal Academy dinner in April 1770) and possibly one identified as Andreas Everard van Braam Houckgeest in the Rijksmuseum. Anthony Askew (before the appearance of Thomas Todd) was the only definite attribution to Chitqua. Askew (1722-74) was a veteran of the East but also had a wide ranging book collection and was known as a bibliophile which may have been how he and Chitqua met. There are tantalising references to other sittings for Chitqua while he was in Britain, such as Josiah Wedgwood, but no statuette is known. In addition, Chitqua was on familiar terms with scholars and collectors such as Sir William Chambers who referenced Tan Chet Qua of Quang –Chew-Fu in his Dissertation on Oriental Gardening 1773 (2nd edition) so he may well have modelled likenesses for him. What has been noted is that Chitqua mastered a rudimentary form of English so that he could communicate with sitters and scholars and that he was invited to translate or comment on manuscripts English for these people.

5. Joseph Collet (1673-1725), Merchant and administrator in Sumatra and Madras, by Amoy Chinqua, painted unfired clay statuette, 1716 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Other examples of clay portrait figures were manufactured in workshops in Canton by artists who usually remained anonymous. The figures were then shipped back to western Europe which presumably accounts for their relatively small size. But one earlier artist has been well documented, namely Chinqua, active 1716. There is at least one example in a British collection, the National Portrait Gallery, of Chinqua’s work, a portrait figure of a merchant Joseph Collet, 1716 (Fig. 5). This figure like that of Todd remained in the family’s possession until being acquired by the public collection, probably ensuring its survival as well as establishing a good provenance. There is no indication that Chinqua came to Britain but much evidence that English merchants operating in Canton were very enthusiastic about sitting for these clay modellers and sending the figures back to Britain as evidence of their good fortune and new affluence. Collet ‘s figure was sent back to his daughter with a very poignant letter.

The Chitqua statuette acquired by the Museum of London however depicts Thomas Todd, a London druggist and tea dealer, who established a long lasting drug, tea and confectionary businesses in Fleet Street in the latter part of the eighteenth century. The face would have been modelled by Chitqua from memory and the features achieve a startling photographic realism. This object is likely to have been made from unfired clay reinforced with hair or tow with a polychrome surface which has been painted or gilded over a white ground of either gesso or fine clay. The head was made separately and is removable from the body just above the collar. The unfired clay is held together by a bamboo armature inside the statuette and has no doubt survived because it has always been in the same family passed down by Todd’s descendants.

Thomas Todd is a figure of particular interest to the history of London. He epitomised the kind of business acumen which ensured the growth of Britain’s industrial, mercantile and commercial empire in the eighteenth century. Born in 1726 in Sunderland he moved to London in 1753 with his older brother Richard and was apprenticed to Ralph Willson on 17 October 1753, who was a druggist and member of the Salter’s Company in the City of London. Todd himself became a member of the Salter’s Company on 10 November 1760. He is mentioned in the Old Bailey records in 1767 in a case of the theft of three pounds in weight of tea from his shop at 79 Fleet Street and also in the 1768 London Directory as occupying a shop at 70 Fleet Street at which he is described as Salter, druggist and tea dealer. There are no records of Todd travelling to China or any business he may have carried out there personally. The two businesses were still registered to and insured by a Thomas Todd in 1794/5 (although this may have been the nephew also called Todd). No record has yet been obtained of a marriage or children nor of his date of death; his nephews took over the businesses and it is through this family line that the statuette has been handed down.

Todd, therefore, is significant as one of the many successful tradesmen who having migrated to London to learn new skills in the mid-eighteenth century founded a successful and thriving business. In addition, the discovery of this carefully modelled and painted statuette sheds some light on the lesser known world of druggists (difficult to locate because they learnt their trade through apprenticeships and were not required to take examinations or register with any organisation before 1841) by precisely illustrating the dress worn by this type of London merchant c.1770. The length of waistcoat, shape of pocket, width of cuff and shape of shoe all point to a date of 1760-70 and therefore place Todd in London at the same time as Chitqua. How he met Chitqua, whether it was through a tea connection remains intriguingly unknown although in geographical terms the two men would have lived very close to each other.

Provenance

Thomas Todd c. 1770; on his death to nephew Thomas Todd; on death 1826 to son R.J.S. Todd; on death to R.J.U. Todd in 1888; on death to Richard Todd in 1962.

References

Gentleman’s Magazine 1771, XLI, pp. 237-8.

William Chambers Explanatory Discourse by Tan Chet-qua, of Quang-Chew-fu, Gent., an appendix to the second edition (1773) of Dissertation on Oriental Gardening (1772),

Gentleman’s Magazine 1797, vol. 67, p. 1072.

John Bowyer Nichols, Illustrations of the Literary History of the Eighteenth Century, Vol 5, 1817, p. 318.

William Carmichael, The Golden-Headed Cane, 1827, London.

Eliza Meteyard, The Life of Josiah Wedgwood from his private correspondence and family, Vol 2, 1866, p. 231.

W.H. Whitley, Artists and their Friends in England, Vol 1, 1928, p. 270.

Aubrey Toppin, ‘Chitqua, The Chinese Modeller, and Wang-y-Tong, The Chinese Boy’, in Transactions: English Ceramic Circle, Vol 2, no. 8, 1942, pp. 149-52.

David Piper, ‘A Chinese Artist in England’, Country Life, 18 July 1952, p. 198.

RJ Charleston, ‘Chinese Facemakers’, Antiques Magazine, May 1958, p. 459.

‘Moulding A Physiognomy- A Chinese Portrait Figure’, V&A Album No. 3, 1984, pp. 47-52

David Blayney Brown, Ashmolean 1985.

Simon Chaplin, ‘Putting a name to a face: the portrait of a ‘Chinese Mandarin’, The Hunterian Museum Volunteers Newsletter, Issue 3, Spring 2007, p.12-13.

D Clark, Chinese Art and its encounter with the world, 2011, Hong Kong University Press.