An audience with Dr William Hunter by Sarah Backhouse

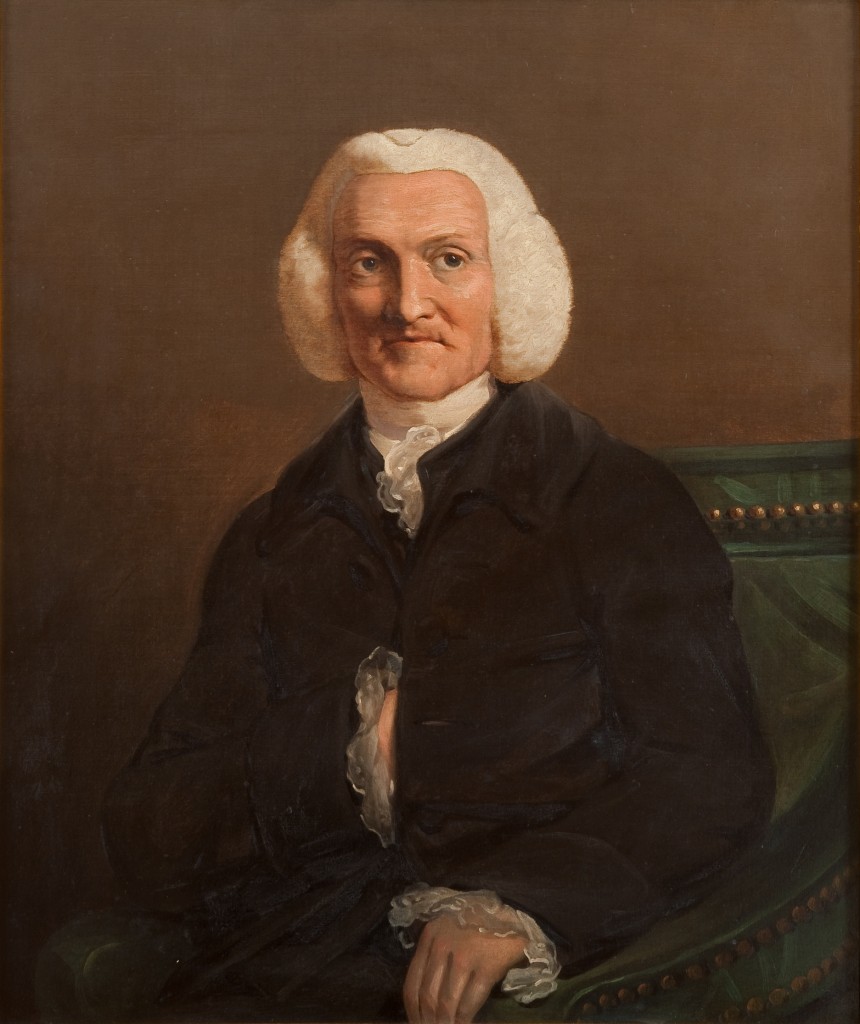

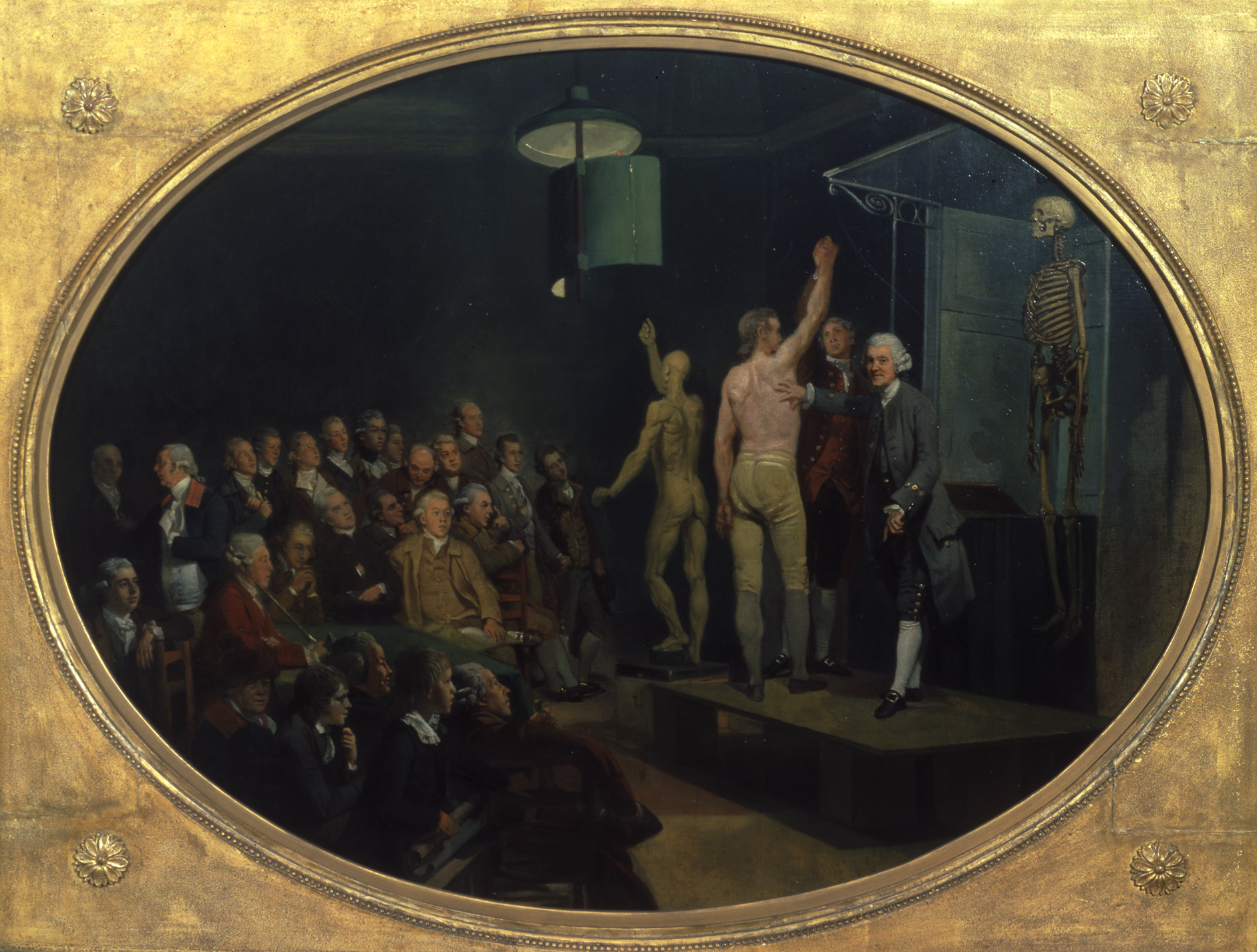

Dr William Hunter lecturing by Johan Zoffany, c.1770-1772. Royal College of Physicians, London

In 1825, ‘Mrs Baillie’ bequeathed a remarkable conversation piece by Johan Zoffany to the Royal College of Physicians (RCP). This painting represents the Scottish-born anatomist, surgeon and midwife Dr William Hunter giving an anatomy lecture to a group of individuals. Mrs Baillie was the wife of Dr Matthew Baillie, Hunter’s nephew and heir. While living in London, Hunter built up a superb library and collection of anatomical preparations, medals, prints and natural history specimens, the vast majority of which were posthumously donated (at Hunter’s bequest) to the University of Glasgow, as the foundation of the Hunterian Museum. The Zoffany painting, however, eluded this fate to become part of the RCP’s 230-strong portrait collection.

The RCP’s portrait collection features predominantly seated middle-aged male doctors; Zoffany’s portrait of Hunter actively lecturing provides a lively contrast, and tells a really interesting and dynamic story – the problem is, we are not really sure exactly what this story is!

William Hunter (1718-1783) ran a successful surgical and midwifery practice in London. He was a member of the RCP, and became physician-in-extraordinary to Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, and attended all but one of her fifteen births. Hunter’s successful medical practice enabled him to establish his own anatomy school on Great Windmill Street, London, in 1767, with lecture theatres, a library, a museum and a dissection room. The following year Hunter was elected as the first professor of anatomy at the newly established Royal Academy of Arts (RA).

It is generally acknowledged that Zoffany’s painting represents Hunter in his role as professor of anatomy, lecturing to members of the Royal Academy. Hunter is the figure to the right-hand side of the composition, with one hand on the back of a live model and an outward gaze that directly engages the viewer. Only one of the other 27 figures in the composition can be positively identified – this is the figure in profile to the centre-left of the audience group, wearing a red coat and holding a slender gold-coloured ear trumpet to his ear. This is Sir Joshua Reynolds, founding member and first president of the RA.

However, none of the other figures can be positively identified as individuals of the RA, neither can the room depicted be firmly located within the RA’s first home in Pall Mall, or its temporary second home at Old Somerset House. Even the date of the painting and its commissioner are contested. So, although this is the most significant painting in the RCP’s portrait collection, we don’t know for certain who it shows, where it is set, who wanted it painted, or even what is really going on – it certainly doesn’t look like a lecture delivered by a professor to a group of young students. These are all questions I wanted to explore further with the help of my Understanding British Portraits bursary.

My initial investigative approach was to meet with academic experts who have worked on Zoffany and this painting, to pick their brains and identify any untapped routes of exploration. I am very grateful to Martin Postle, Deputy Director of Studies at the Paul Mellon Centre, for sharing his thoughts and pointing me in a fascinating direction. Perhaps, in order to understand more about this painting, we should look more into Hunter’s lectures themselves, his dissections, their audiences, and the context in which they took place in the 1770s. It is possible that some figures in Zoffany’s painting are not members of the RA at all, but rather representative of audiences with a more general interest in anatomy and a bit of gore…

A lecture at the Hunterian Anatomy School, Great Windmill Street, London, by Robert Blemmel Schnebbelie, watercolour, 1830. Wellcome Library, London.

This watercolour a rare representation of a lecture at William Hunter’s anatomy school at Great Windmill Street, London. Hunter died in 1783; this painting shows a successor teaching about the bones of the skull.

Great, some research into dissection and anatomy lectures seemed right up my street, so I made arrangements to visit Glasgow for a few days, in particular the Special Collections department based at Glasgow University’s library, and the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery. As the repository for Hunter’s collections and correspondence, including his lecture notes, I hoped to find some sort of evidence that would shed some light on any of the long list of questions I have about the painting…

Success! Well, sort of. Many of Hunter’s letters and lecture notes in Special Collections are well known and have been published by Helen Brock; I did however come across some little (unpublished) notebooks written by a certain William Hamilton in 1779, who attended Hunter’s anatomy lectures at the RA. Special Collections have catalogued these notebooks as belonging to William Hamilton (1758-1790), professor of anatomy and botany at the University of Glasgow, 1781-1790. This is fantastic, as these notebooks suggest that peers who were not members of the RA were permitted to attend Hunter’s lectures there, and may well have made their way into Zoffany’s painting, opening up all sorts of possibilities for further identifications.

However, my excitement was short-lived, as I have since discovered that there was also a painter called William Hamilton who was a student at the RA from 1769-1784. It seems likely that this is in fact the Hamilton who wrote such detailed lecture notes. Nevertheless, these notes are evidence of a student at the RA who attended a course of Hunter’s lectures in 1779; a little late for Zoffany’s painting so alas, Hamilton is probably not one of the two young boys depicted in Zoffany’s audience. I was not to leave empty-handed, however, as Hamilton did offer up a rather wonderful discovery: on the back of one of his notebooks, Hamilton doodled a little sketch of what looks like a figure performing a dissection. This delightful sketch could possibly be a new, unpublished portrait of William Hunter…if so, this is a really exciting find, and will be the focus of on-going work this year.