Sir Joshua Reynolds: Sketchbooks to Genius by Paul Willis

Reynolds Sketchbook (PLYMG Page 46r) by Joshua Reynolds (detail) © Plymouth City Council (Arts & Heritage)

Sir Joshua Reynolds is a pivotal figure in the development of the British School of painting, principally through his writings on art and his portraits. However, besides the research conducted by Giovanna Perini Folesani, Reynolds’ Italian Sketchbooks have received little critical attention. This is possibly because his sketchbooks have been generally overlooked in favour of his portraits and his later attempts at ‘history’ paintings. However, Reynolds sketchbooks constitute not only a significant influence on his immediate output on his return to England in 1752, but may also help to understand how he established himself as the fashionable portrait painter of the day.

This blog post will highlight some initial findings on the position of Sir Joshua Reynolds’s sketchbooks, composed during his time in Italy studying Old Master works (1750-1752). I compared the four Reynolds Italian sketchbooks held at the British Museum (x2), Sir John Soane’s Museum and the Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery in regard to his portraiture completed on his return to London.

Introduction

In the early 18th Century, it was noted that a successful portrait painter must have the name of having travelled to Rome. However, Reynolds did not travel there to learn technique, which he felt he had acquired from his apprenticeship with Thomas Hudson (1740-3). His inspiration to travel was similar to scholars of the period who wished to study Greek and Latin in order to stock their minds with apt quotations and allusions. Reynolds wished to fill his mind with the colour and drama from Italy’s glorious tradition of art. By spending time in palaces, churches and private galleries, Reynolds planned to study faces, expressions and gestures, the arrangement of points of interest, the treatment of chiaroscuro, and how colouring can enhance the effect of a composition.

Reynolds resided in Rome for two years, painting caricatures, sketching and making copies of Old Master paintings. His sketchbooks reveal that he was instinctively drawn to the art of the later 16th and 17th century. At this stage in his career, he was not bound by particular sets of academic values or prejudices. His choice of Old Master works to study ranged over the whole field of Italian 16th, 17th – and some 18th century art, by-passing any preconceived hierarchy of genres or painters. One possible explanation for this varied accumulation of visual and written material is for its practical purposes in portraiture. In consequence, most of his sketches are compositions of single figures and small groups, mementoes of costumes, attitudes, textures, colour, shading, and space.

Leaving Rome in April 1752, and after a brief visit to Naples he went to Florence in May, travelling via Assisi, Perugia, and Arezzo. In Florence Reynolds studied works in the Pitti Palace, including Raphael’s Madonna della sedia, and Titian’s Mary Magdalen – ‘an immense deal of hair, but painted to the utmost perfection.’(BM sketchbook, (1859,0514.305, page 29 verso).

By early July 1752 Reynolds had left Florence for Bologna, where he showed an admiration for Ludovico Carracci, an artist whom he respected throughout his life. After ten days in Bologna, Reynolds travelled to Venice via Modena, Parma, Mantua, and Ferrara, reaching Venice after three weeks, where he studied the technical methods of the great Venetian colourists Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese.

Reynolds left Venice in early August 1752, and travelled to Padua, Milan, and Turin. At the end of August, he crossed the Alps and journeyed on to Paris where he stayed for a month. He finally returned to England in October 1752.

The Sketchbooks

The sketchbooks in the British Museum (BM), Sir John Soane Museum (SJSM) and the Plymouth City Museum & Art Gallery (PCMAG) are rare survivors from Reynolds period in Italy. Only ten sketchbooks went to auction at Mary Palmer, Marchioness of Thomond, [Reynolds’ favourite niece] posthumous sale in 1821 – the majority are now held in public collections, including the British Museum [x2] (London), Sir John Soane Museum (London), Metropolitan Museum (New York), Fogg Art Museum (Massachusetts), and Beinecke Library, Yale University (New Haven). The PCMAG sketchbook was acquired by private treaty in 2014 through the generosity of the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Art Fund, the V&A Purchase Grant Fund, and the Friends of Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery. It was one of the last two remaining in private hands. The sketchbook is significant for its rarity and for the opportunity it represents to bring insight into Reynolds time in Italy.

The BM sketchbooks were produced by Reynolds on his travels from Rome to Florence and then to Venice. The sketchbook (1859,0514.305) contains travel notes, drawings and notations relating to the works of Old Masters he viewed in Florence and on the journey from Rome to Florence, 1752. The other sketchbook (1859,0514.304) contains notes and sketches, mainly from paintings and sculpture, made in the second half of 1752 on the journey from Florence to Venice.

The SJSM sketchbook (SM Volume 32) derives from works in Bologna and Naples. This sketchbook numbers ninety-six leaves, bears the number ’63’ written on its vellum cover, and corresponds to the description of Lot 63 in the catalogue of the Marchioness of Thomond’s sale, Christies 1821. There is also a ‘smaller’ sketchbook held at the Museum, yet its attribution to Reynolds is in doubt. It was rejected by Ellis Waterhouse, who mentions only the larger sketchbook.

The PCMAG sketchbook was created between 1751 and 1752, and contains 121 sides of drawings by Reynolds in pencil, pen and ink, and black chalk. It is bound in its original vellum binding and cover. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts Reynolds exhibition (1986) as catalogue number 159, where Nicholas Penny recognised one of the drawings (above) as a study of Correggio’s Madonna di San Girolamo (Galleria Nazionale di Parma, Parma). It is likely that the sketchbook contains drawings from Reynolds time in Rome (1751) and his journey to Venice, particularly Florence and Parma (1752).

The sketchbooks reveal how Reynolds would focus on a particular aspect of an Old Masters work and sketch, what we presume for him, was the most interesting or useful aspect of it. In the case of Correggio’s Madonna di San Girolamo it is the character and composition of the angel holding the Bible before the Christ Child that most interested him. One can assume that Reynolds knew of this work as it was famed throughout the 17th and early 18th centuries as one of the most beautiful paintings created. Vasari admired the wondrous colour, the smile of the angel and wrote that it could cheer up even the most melancholy of observers. Interestingly, although the sketch is found in the PCMAG sketchbook (above) a reference is found in the BM sketchbook (1859,0514.304, page 12 recto) whereby Reynolds, possibly writing a letter draft, writes: “…you must ask to see the Holy Family with St. Jerom. It gave me as great a pleasure as ever I receiv’d from looking on any picture, the airs of the heads, expression and colouring are in the utmost perfection; ’tis very highly finished, no Giallo [yellow] in the flesh, the shadows seem to be added after by a thin colour made of oil and ultramarine, and sometime oil and red, no outline scar[c]e to the face especially the Virgins…the red mixt with the white of the face almost imperceptible…” This statement reinforces Reynolds interest in the techniques of the Old Masters, especially in their treatment of expression, colour and design.

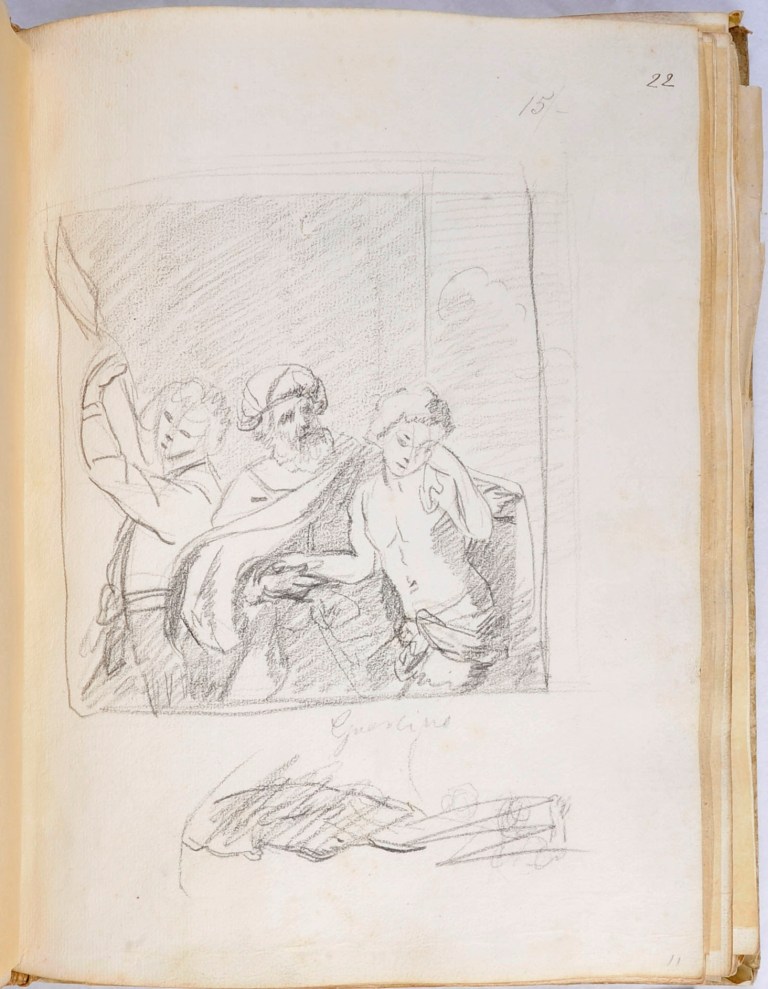

This initial research has also discovered that on occasions Reynolds would write a note regarding a work in one sketchbook whilst the sketch relating to the work may be found in another. For instance, in the BM sketchbook, (1859,0514.305, page 29 verso) Reynolds references a work by Salvator Rosa The Temptation of St Anthony, which he viewed at the Palazzo Pitti, Florence. He writes: “…a Salvator Rosa, a St. showing the Cross to a grotesque figure.” However the sketch of this work (above) can be found in the PCMAG sketchbook (PLYMG.2014.72, page 47 recto). Another example of this is in the SJSM sketchbook (SM Volume 32, page 5 verso) whereby Reynolds mentions viewing the The Return of the Prodigal Son by Il Guercino which he had sketched in the PCMAG sketchbook (PLYMG.2014.72, page 22 recto; see below). There may be many reasons why Reynolds may have worked this way. Perhaps he used two sketchbooks when visiting the sites to study the Old Masters, or he may have written notes after his visit, or the sketch may have been completed after the visit from a print. However, the more likely scenario may be that he used his sketchbooks intermittently, (in particular the PCMAG sketchbook, which has sketches from a variety of locations and sources) without any specific or obvious logical progression or rationale. Further research may develop a greater understanding of his working practices during this time. Moreover, it is interesting (or perhaps further complicating) to note that the BM sketchbook, (1859,0514.305, page 54 recto)and the PCMAG sketchbook (PLYMG.2014.72, page 57 verso) have a sketch of the portrait previously identified as Daniele Barbaro by Paolo Veronese (Palazzo Pitti, Florence) (Interestingly, Reynolds thought this work was by Titian). To add even more complexity, Reynolds did not always copy exactly what he saw before him. There were occasions when he would combine several works together to make a hybrid.

In his Second Discourse he stated:

Instead of copying the touches of those great masters, copy only their conceptions; instead of treading in their footsteps, endeavour only to keep the same road. Labour to invent on their general principles and way of thinking. Possess yourself with their spirit.

Return to England

While still in Italy, Reynolds held concerns on whether to extend his studies or return to London. In a draft letter written in the BM sketchbook (1859,0514.305 page 8 verso), Reynolds highlights his concerns. “…I remember it used to be a continual subject of Discourse of my Fathers when he discoursed on Education not to be in too great a hurry to show oneself to the world but to lay in first as strong foundation as possible of knowledge and learning; this may very well be apply’d to my present affairs; by being in too great a hurry perhaps I shall ruin all and arrive at London without reputation & nobody that has ever heard of me…”

Arriving in London after a brief stay in Devonshire, Reynolds established himself in St. Martin’s Lane, and set out to demonstrate the impact that his Italian travels had had on his art. The first painting to attract public attention was the heroic full-length portrait of Commodore Augustus Keppel (National Maritime Museum, London) striding along a storm-lashed shore. It was no accident that Keppel’s pose duplicates the famous statue, the Apollo Belvedere, which Reynolds would have seen at the Vatican. The composition is also close to one painted by Allan Ramsay – the then leading painter in London – who used the pose for his portrait of the Scottish chieftain Norman MacLeod (Private Collection). But perhaps most importantly, the dramatic lighting affects seem to be inspired by the works by Tintoretto which he would have viewed in Venice. The green-blue-grey colour scheme is highly original, especially in comparison to other naval portraits of the mid-18th century. Written in pen and ink in the BM sketchbook (1859,0514.304, page 71 verso and page 72 recto) Reynolds praises Tintoretto’s Marriage at Cana in Galilee (Santa Maria della Salute, Venice) “This Picture has the most natural light and shadow that can be imagined… there is not too much white in the picture…the shadows blue Ultr. strong. Shadows of the Table-cloth Blueish, all the other colours of the draperies are like those of a washed drawing. One sees indeed a little lake drapery here and there, and one strong yellow…This Picture has nothing of mistiness…” It is possible that these notes were influential in the colouring of the Keppel portrait.

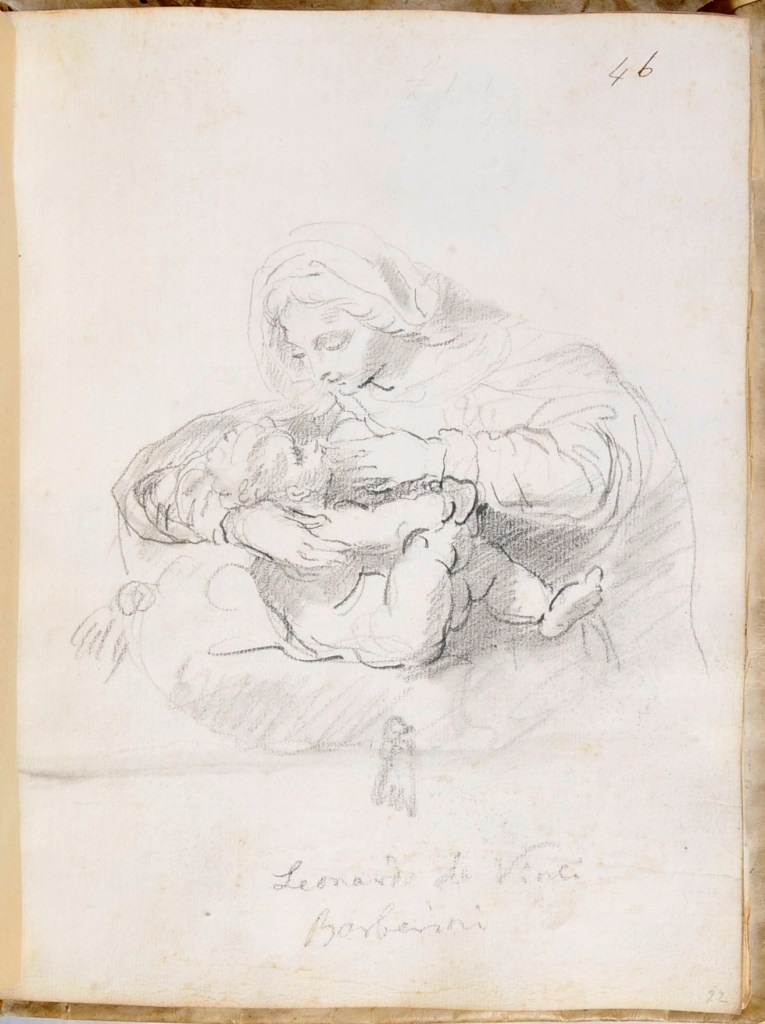

Initial research suggests that there is a possibility that some of the sketches from Reynolds’s Italian sketchbooks may have been a starting point for a number of his portraits. However, some reservation must be made as Reynolds was an avid collector of Old Master drawings and prints, so to qualify the influence on one source may be misleading or at worse, pure simplification of his work practices. Nevertheless, the sketchbooks may on occasion have been used as a source of inspiration such as an author would reference a notebook to recall jottings relating to an overheard conversation, an individual’s character traits, or an episode from life. For instance, in his celebrated portrait of Robert Orme, (National Gallery, London) the design of the horse lowering its head could be referenced from the BM sketchbook (1859,0514.305, page 54 verso). The overall impression of this sketch of an animated horse, head lowered, ready for action, may suggest a connection. In addition, the portraits of Horace Walpole and Laurence Sterne (both National Portrait Gallery, London), positioned by a desk of papers and writing equipment with one hand resting on their hips while the other raised to their faces as if in thought, may be reference to a portrait by Bronzino which Reynolds sketched in Palazzo Corsini (BM sketchbook (1859,0514.305, page33 recto). In the PCMAG sketchbook (PLYMG.2014.72, page 46 recto) there is a sketch of Madonna with the Green Cushion by Andrea Solari (below). Reynolds obviously found the tender relationship established between the two figures agreeable. He later replicated this scene in his work Mrs Susanna Hoare and Child, (Wallace Collection, London). (Interestingly, Reynolds thought this work was by da Vinci). Furthermore, a sketch of Charity found in the SJSM sketchbook (SM Volume 32, page 27 recto) seems to suggest a direct compositional reference to Reynolds portrait of Lady Cockburn and her Three Eldest Sons (National Gallery, London).

Conclusion

Overall, the sketchbooks are a visual record of Reynolds’ artistic eye, his thought processes and his personal interests – a rare private and personal insight into an artist whose work and life were to become so public in the future. The sketches also inform us about what he sought out on his travels. It is thought that he made the sketches in situ, sometimes making notes as to the use of colour and shade, and often noting the artist’s name (and on a number of occasions being mistaken). We also see flashes of his skill in drawing from life. The sketches range from coarse, sketchy line drawings, some with colour coding, to more built up, shaded, and developed pictures. It is also interesting to observe his interest and analysis of ‘chiaroscuro’. Many years later Reynolds wrote:

When I observed an extraordinary effect of light and shade in any picture, I took a leaf of my pocket-book, and darkened every part of it in the same gradation of light and shade as the picture, leaving the white paper untouched to represent the light, and this without any attention to the subject or to the drawing of the figures. A few trials of this kind will be sufficient to give the method of their conduct in the management of their lights.

Reynolds did not imitate the style of the paintings he was copying: all his drawings are in his own style. This often makes the identification of the sources of his sketches difficult. On stylistic grounds alone it is difficult, and when his method of working is included, it becomes problematic to gauge whether a drawing is a representation of a particular work of art or a construction of his imagination.

The research to date has highlighted a number of links between the Reynolds sketchbooks and their possible preliminary influence in regard to his portraiture. However, there are still more questions than answers. To understand the major impact of the sketchbooks on the transitions in Reynolds’ work further investigation is required which may act as a prelude to further debate in this area of study.

Thank you to the staff at the British Museum, Print Room, Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery, and Sir John Soane’s Museum for their assistance with this research.

Comments

I’m very interested in tracking down copies of original hand written letters by Sir Joshua Reynolds dating from October 1740 -1750. Can you help me please. Many thanks.

Regards.