Collaging people: James Joyce and Early Pop by Katy Norris

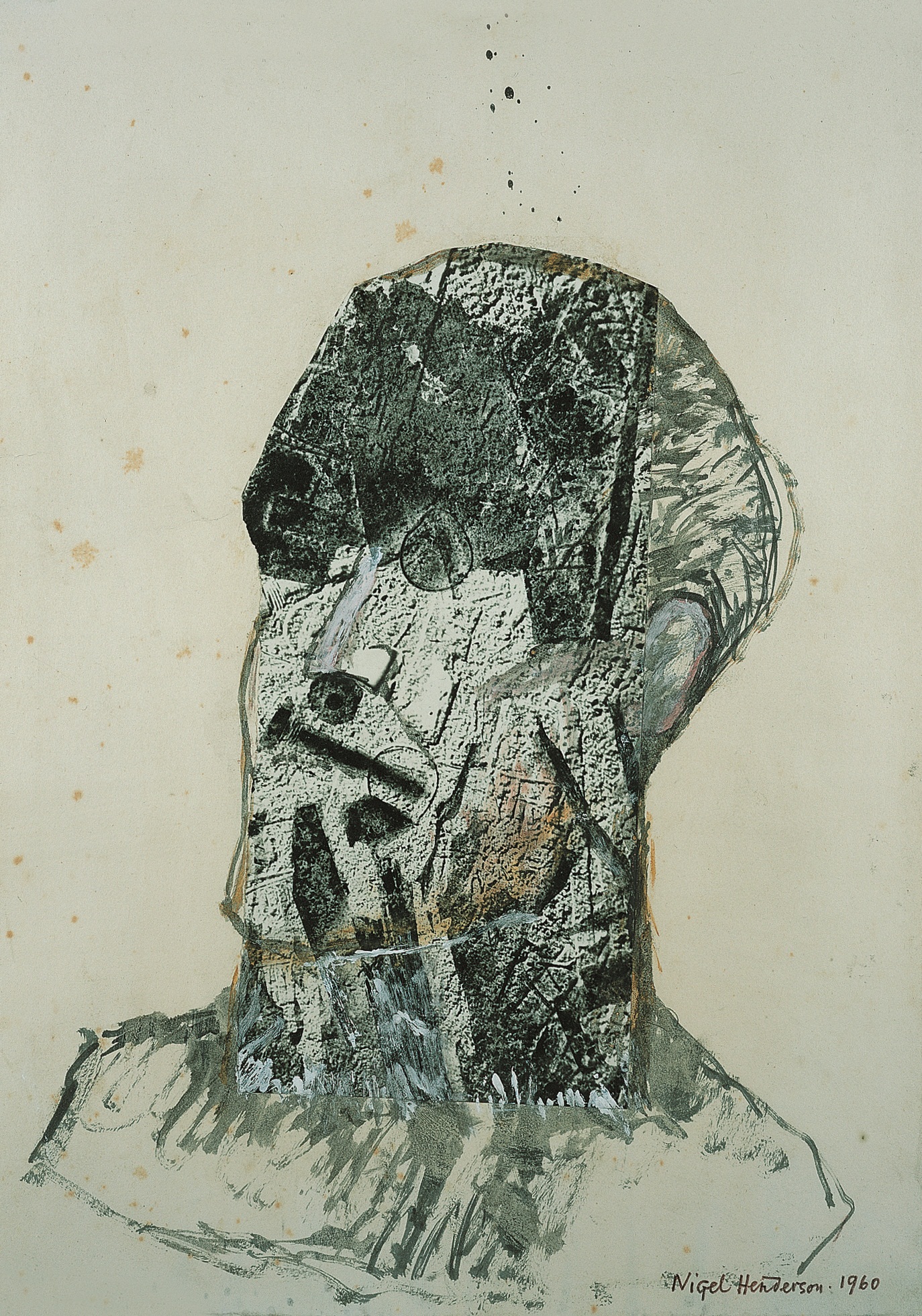

Head of James Joyce by Nigel Henderson, c.1960, collage and photographic processes on paper. Pallant House Gallery: Wilson Gift through The Art Fund, 2004.

This year I have been a fortunate recipient of the UBP bursary, an opportunity that has allowed me to learn more about specific artworks in Pallant House Gallery’s collection of British Pop Art. The benefits of my research have had huge impact, none more so than in my ability to curate informed exhibitions and displays using the collection.

A good example can be seen in the Gallery’s newly opened summer programme, which features an Eduardo Paolozzi retrospective alongside an exhibition of Modern British collage curated by myself. A major focus for the display is a selection of portraits by Pop artists as well as “proto-pop” collages by members of the Independent Group such as Eduardo Paolozzi, Richard Hamilton and Nigel Henderson. Central to this is Henderson’s ‘Head of James Joyce’, c. 1960, in which it is just possible to decipher the writer’s jutting chin and circular rimmed spectacles. Composed of collaged fragments taken from ‘stressed’ photographs of rock strata and other natural forms, the work holds an obscure position in the development of Pop Art, being far more ambiguous than the glossy portraits of film stars and music heroes created by Andy Warhol and Peter Blake. Joyce simply didn’t have the same instant recognition that Pop icons such as Marilyn Monroe, The Beatles and Elvis Presley later had.

One way of unlocking the meaning of Henderson’s portrait is to consider its relationship to an earlier collage entitled ‘Head of a Man’ (1956). Created for the ‘Patio and Pavilion’ section of the ICA’s landmark exhibition ‘This is Tomorrow’, this anonymous, putrefied head hung at the centre of a makeshift Brutalist structure designed by the architects Alison and Peter Smithson alongside Paolozzi’s densely encrusted sculptures. The overall look of the pavilion was described as a “cult of ugliness”, a visual manifestation of the existential anxieties prevalent during the post-war era. In this context Henderson’s collage offered a human dimension to the escalating crisis, emphasising the uncertain status of the individual against the backdrop of Cold War division and looming nuclear threat.

Henderson himself said of ‘Head of a Man’: “the face is like a cratered field, one eye is suggestive of a worm in a bud … I sometimes think of the Heads I’ve seen of Archimboldi (sic) … and of those composites the surrealists liked, made of intertwined nudes”. His indebtedness to the Surrealists is obvious since it is only through subconscious association that we are able to make the connection between the decomposing, biomorphic fragments of collage and the heavy atmosphere of the Cold War age. Perhaps even more revealing is the influence of Giuseppe Arcimboldo and his invented portraits formed of composite fruit, vegetables, flowers and fish. It puts ‘Head of a Man’ and subsequently the related ‘Head of James Joyce’ squarely within the context of fantasy portraits, a genre that NPG curator Paul Moorehouse has recognised as being central to the evolution of Pop Art.

A notable precedent for fantasy portraits in Pop Art is Paolozzi’s collage series based upon Time magazine covers, examples of which can be seen in the retrospective at Pallant House Gallery this summer. In these collages Paolozzi appropriated recognisable faces from the news and media, only for them to be cut-up and rearranged to form an imaginary person. Thus in the ‘The Return’ (c. 1954) the jawline of the Black Haitian president Paul Magloire is combined with the nose and forehead of the white businessman Robert E Wood. These uncompromising modifications betray the same Brutalist influences that informed ‘Head of James Joyce’ and yet, rather than merely disfiguring the subjects’ appearances, here collage has been used transformatively as a means to create an entirely new individual.

A kind of perverse optimism underscores the Time collages. While they openly subverted conventional portraiture the series also opened up a more inclusive approach to selecting, reproducing and redistributing images of people. During the formative years of Pop, shaped by the Independent Group’s interest in both ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture, pictures of writers, presidents and politicians rubbed shoulders with bodybuilders, movie stars and pin-up girls. The collages drew from an extraordinarily diverse pool, which ranged from images with popular appeal to those whose meaning was limited to a specialist circle of cultured cognoscenti.

James Joyce and Dancer: Monument to Trieste, still from The History of Nothing by Eduardo Paolozzi (1960-62), collage on paper.

Pallant House Gallery: Wilson Loan, 2006.

Amongst the selection for Pallant House Gallery’s Paolozzi exhibition is a small collage entitled ‘James Joyce and the Dancer’ (1960-62). The work features an unlikely pairing of Joyce with the silhouette of a female dancer whose body is composed of robotic parts. The work was amongst the collaged stills that Paolozzi filmed for his short film ‘The History of Nothing’. No doubt he was inspired to incorporate Joyce’s image primarily because of the parallels between the author’s intuitive writing style and the fragmentary sequence of the film. Indeed Paolozzi’s contrast between man and machine has more to do with Joyce’s ever-shifting metaphors and experimental wordplay than capturing a specific likeness or character trait. The collage represents a playful juxtaposition which, like Henderson’s portrait of Joyce, roots Paolozzi’s art in the legacy of Modernism and Surrealism. At the same time its dynamic energy looks forward to new technologies, popular music and the growth of consumer commodities, all of which paved the way for Pop Art during the mid-1960s.